The blurry surveillance camera footage from Kuala Lumpur’s international airport showed a woman in white approaching the estranged half-brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un from behind. She daubed his face with a toxic substance—which one, investigators did not yet know. Kim Jong-nam died on February 13, en route to the hospital.

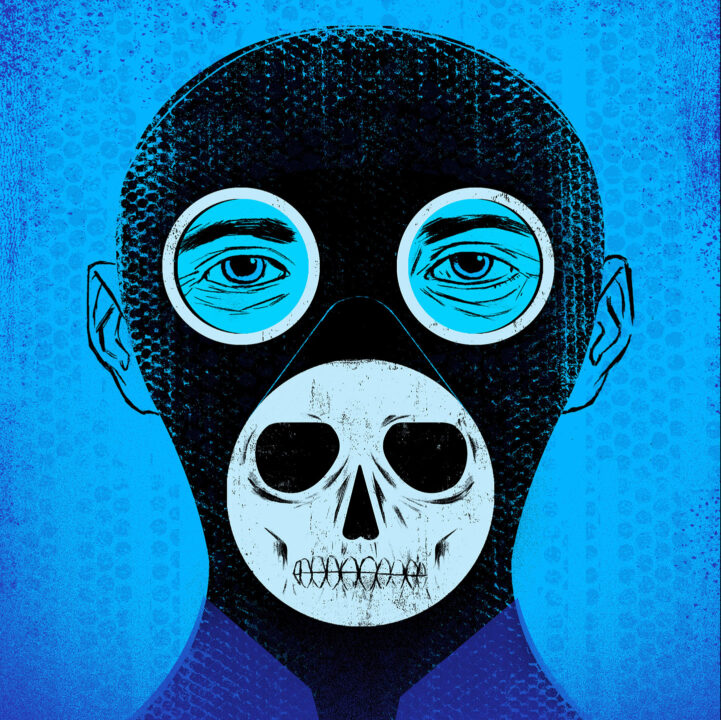

Over 8,500 miles away at the Center for Nonproliferation Studies in Monterey, California, Raymond Zilinskas watched the video on the New York Times website and followed reports on Kim Jong-nam’s death. As director of the chemical and biological nonproliferation program at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies, his office is like a mini-museum of chemical and biological weapons protection gear. Standing near the entrance is a life-sized mannequin in mud-colored, heavy rubber, full protective gear from World War II. Above his desk sits a brunette mannequin’s decapitated head, enshrouded in a gray gas mask shaped like a horse’s snout. The same masks were passed out to protect civilians during the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, Zilinskas explains during my recent visit.

Nearby, another doll head with long-lashed eyes, this one draped in blue and pink Mardi Gras beads, wears a gas mask once used by the Israelis. And in a corner, a dummy sports rubber boots and a gray apron over white protective cloth that cloaks the face, mouth, and head, with only the eyes visible under protective goggles. The Soviets used such suits in the 1940s and ’50s to catch rodents, Zilinskas says. They would take gerbils out of the traps and comb them for ectoparasites, which would fall into the pots of oil they carried. “They would take it all to the lab,” he says, looking for Yersinia pestis—an organism that causes bubonic plague.

Viruses, contagions, contaminants, and germs—he knows how they can kill you when used as weapons, which is why soon after Kim Jong-nam’s death Zilinskas began fielding questions from journalists. Malaysian authorities reported that there had been a second face-smearer, also a woman. One of the suspects appeared on the surveillance footage in a T-shirt with “LOL” on its front. The two were apparently hired assassins for the North Korean government. Of all the mysteries, one in particular burned: Which poison might have killed him?

At first, Zilinskas says, “I thought it was cyanide,” a substance once used by KGB agents. “They would squirt a cloud of cyanide, and when that happens the person who is receiving it goes ‘Huhhhh,’” Zilinskas says, sucking in air. He is 78, in gray jeans and loafers, with a tuft of white hair and white eyebrows that dip into a V-shape when he talks. “It takes a minute, maybe two minutes. Boom. Gone.”

But when Zilinskas heard how long it took for Kim Jong-nam to die—20 minutes—he knew it could not have been cyanide. Something just as potent and paralyzing was at play, and it may have offered one of the clearest affirmations yet into the extent of North Korea’s chemical weapons capabilities.

Ten days after Kim Jong-nam’s attack, Malaysian authorities reported that the killers had used the nerve agent VX. That’s when the deluge of emails and phone calls to Zilinskas from around the world really started. A reporter for the Los Angeles Times wrote him: “It’s a big story, and everyone’s scrambling—and you know this issue better than most.”

Beyond his collection of doomsday paraphernalia, Zilinskas is one of the world’s foremost experts on chemical and biological weapons. He is frequently called upon to answer questions about such topics not only by journalists, but by other academics, historians, governments, and even Hollywood writers. Zilinskas recently served as an advisor to the FX television show The Americans, helping the writers and producers grasp plot lines involving lethal pathogens.

His exhaustive research has taken him around the world to Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Tajikistan, and beyond. He spent 11 years conducting dozens of interviews with former Soviet scientists, and combing through documents and intelligence files to cowrite, along with Milton Leitenberg, The Soviet Biological Weapons Program, a stunning 921-page investigation published in 2012 by Harvard University Press.

The book uncovered a large-scale offensive biological weapons program, detailing how the Soviet Union amped up its production facilities using microbiology to weaponize bacteria and viruses, and alter pathogens to make them resistant to vaccines. The Soviets hired tens of thousands of scientists and technicians for this undertaking, despite having signed the Biological Weapons Convention in 1972, which bans the development, production, and stockpiling of biological weapons.

Zilinskas wrote about how Soviet scientists created new strains of pathogens, genetically engineering Legionella pneumophila (which causes Legionnaires’ disease) to secrete certain peptides along with pathogens, which stimulates a host’s immune defense system—activating immune cells capable of destroying the myelin of nerve cells (destruction of myelin in the human body induces a multiple sclerosislike illness).

Zilinskas’s work also revealed how the Soviets transferred a gene that codes for the production of the diphtheria toxin (which causes diphtheria, a throat and nose infection), into a new host, which was Yersinia pestis (the plague source) to make it more virulent than strains found in nature. And his book documented how the Soviets weaponized Bacillus anthracis, which causes the disease anthrax. Indeed, in 1992, then Russian President Boris Yeltsin admitted that an anthrax accident, which infected 94 people and killed 64 in the Soviet city of Sverdlovsk in 1979, had been caused by its own military development.

“It is frightening because the idea that someone can and is willing to apply science and medicine in order to manipulate and grow microorganisms for the purpose of deliberately bringing about illness and death contravenes so much of our society’s ethics that it is beyond the pale of civilized behavior,” Zilinskas and Leitenberg write. “The possibility that virulent bacteria or viruses will be developed to arm biological weapons and, when used, threaten vast populations with disease and death is incomprehensible.”

Zilinskas tries not to lose sleep over threats that could occur at any time. If he knew a pandemic disease was approaching, he says, he would work to take precautions that would help the community, but he knows “the probability of me being injured while driving is much, much greater than being injured by chemical or biological weapons.”

Yet, as Zilinskas has proven, the possibility is real.

In his research, he visited anti-plague institutes from Soviet times, including one that led to the discovery of a top-secret report about a smallpox outbreak in 1971 in Kazakhstan. “There had been no smallpox in Russia and the Soviet Union since 1936,” Zilinskas thought at the time. So how did the outbreak occur? “What happened here? What was the big mystery?”

He found out there had been an accidental discharge of the variola virus, which causes smallpox, on a small island in the Aral Sea, between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. The virus had drifted off and reached a marine research ship, infecting a 24-year-old fisheries expert who was sampling sea water and sea life specimen like plankton. The ship landed in Aralsk, Kazakhstan, where the infected woman developed a fever and rash. Over the next three weeks a dozen more cases turned up with similar symptoms, traced back to her, and five people died. It turned out the virus had come from open-air tests carried out on Vozrozhdeniye Island—a leak from a Soviet chemical weapons lab.

“I was so upset when I learned that the Soviets had weaponized smallpox virus,” Zilinskas says, leaning back in his office chair. “Smallpox had been wiped out by the world in 1977 . . . so the whole world was susceptible. People weren’t being vaccinated anymore.”

A framed photo behind him shows a version of him from a time when his hair was not white. In it, he wears a short-sleeved button-down with a pocket protector, standing in front of an airplane marked “UN” in blue. It was taken in 1994, when he served as a United Nations biological weapons inspector in Iraq, participating in two expeditions encompassing 84 facilities that were researching, developing, or producing microbial products. “We had to go out to these fields to look at the agricultural helicopters to see if they’d been converted to use chemicals of biological weapons,” he remembers. “That was the hottest I’ve ever been,” estimating it was about 125 degrees at times. The inspectors were followed everywhere by Iraqi minders who monitored and videotaped their visits.

On his desktop computer, Zilinskas pulls up a file with the words Iraq’s BW Facilities Map in neon green. He points the cursor on a map to a desert area where the Iraqis developed and produced chemical and biological weapons in bunkers. He notes Salman Park, a main research laboratory, and Al Hakam-main, a development lab and plant with large fermenters, as well as a foot-and-mouth disease vaccine plant that had some production of botulinum toxin and Bacillus anthracis. “It was exciting,” says Zilinskas, who is still a consultant to the U.S. Department of Defense.

His interest in politics and war began when he was a boy. His parents were from Lithuania, and his mother was pregnant with him when the Soviets invaded. She fled Red Army soldiers and while en route in November 1938 ended up giving birth to him in Tallinn, Estonia. With infant in arms she managed to get onto a fishing boat and make it to Sweden, where Zilinskas was raised speaking Swedish. His English carries faint traces of the accent. He was seven when World War II ended, and he holds onto a vivid memory from a year later when the Soviets sent a ship to the Stockholm harbor intending to cart Lithuanians back. The soldiers stood on the harbor with menacing looks, holding machine guns, waiting to round up and load people. “My family was deathly afraid of being deported to the Soviet Union,” he remembers. “Stalin was not a very nice guy. . . . We all were wondering, ‘Are we going to be shipped out?’”

They did not get sent back. At age 12, he immigrated to the United States, first to Chicago, then to Los Angeles, where he attended high school in San Fernando and joined the Army Reserve after graduation. He was sent to Fort Ord in Monterey for eight weeks, then to Fort Gordon in Georgia to be trained as a military police officer. He was assigned to a U.S. Army Reserve division in Los Angeles as a medic, and spent time training at a military hospital in Fort Ord during the Vietnam War. The experience sparked his interest in pathology in patients. He says he encountered “parasites I’ve never seen. We would have different types of malaria. We would have fecal stuff. People who would have ringworm.”

Zilinskas got his medical technologist license from the state of California, working part time at a hospital where he immersed himself in everything from hematology to blood banking to clinical chemistry and microbiology. He then returned to California and went on to work as a clinical microbiologist for 16 years before entering graduate studies at the School of International Relations at the University of Southern California.

It was the early 1970s, and the first genetic engineering studies were emerging. Zilinskas wrote his dissertation on policy issues generated by recombinant DNA research, and genetic engineering techniques for biological weapons development. While in graduate school, he also remembers taking a European history course and writing a paper on Swedish politics, vis-à-vis the Soviet Union after World War II—inspired in part by that moment from his childhood in Sweden, watching Soviet soldiers with guns looking to deport Lithuanians.

The ascent of his career has run parallel to a period of proliferating questions and concerns over biological and chemical weapons development and control. Even since the Biological Weapons Convention, there has been reason to believe that offensive bioweapons programs have made strides in China, Syria, and Russia, not to mention that deadly agents may be making their way into the hands of terrorist groups.

These perils are evolving, which is what makes Zilinskas’s role on the world stage so important, says Rita Colwell, former director of the National Science Foundation. Colwell also previously served as president of the University of Maryland Biotechnology Institute, where she recruited Zilinskas in 1987 to launch its center on bioethics, microbiology, and biotechnology. He came to the Center for Nonproliferation Studies in 1998. “He’s keenly interested in ethical processes, how one does medicine, how one does science,” she says. “And he cares deeply about policy issues associated with national security and intelligence.”

After the reports linking VX to the Kim Jong-nam attack became public, inquiries to Zilinskas about the nerve agent multiplied. A journalist from the AFP news agency asked him in an email: “How did the attackers avoid coming to serious harm when they appeared to handle it without any form of protection?” and “How was Kim able to walk and get help given how quickly VX is supposed to work?”

As with other nerve agents, Zilinskas explains, VX inhibits the acetyl cholinesterase enzyme, which under normal circumstances breaks down the chemical acetylcholine. When receiving a signal from the neurological system, acetylcholine stimulates muscles to do their normal work. But if acetyl cholinesterase is destroyed by VX or other kinds of nerve agents, acetylcholine does not break down, and muscles go into involuntary contractions.

“Your eye pupils turn to pinpricks,” Zilinskas says. “You start drooling. Your sweat glands start going. You defecate. You urinate. And in the end your breathing is not efficient anymore. You die of asphyxiation.”

As with cyanide, however, pure VX would have taken out Kim Jong-nam in far less than 20 minutes. A single drop can kill. And anyone who came close to it or had the substance on their hands could have died too. “I immediately thought about binaries,” Zilinskas says, explaining that when VX is divided into two separate compounds, each is harmless on its own, and each can work in a slower release form. But when mixed together, the chemical result becomes a deadly weapon. This would explain the involvement of two suspected face-smearing women: “One has the precursor, the other comes and smears it,” Zilinskas says. “Now there is VX.”

There were news reports that one of the women involved ran to the bathroom after the attack, which also fits with Zilinskas’s suspicions, because the effects of VX can be mitigated if quickly washed off. “It seems to me at least one of them must have had training in how to do this,” he says.

North Korea is not a state party to the Chemical Weapons Convention, but it is part of the Geneva Protocol, which forbids chemical and biological weapons in warfare. “We have known they have a big chemical industry, so they certainly have the capabilities to produce any chemical they want to,” Zilinskas says. “We’ve been thinking for a long time that yes, they have chemical weapons. . . . Now, if it’s really the North Koreans behind this, it’s proof.”

On Zilinskas’s desk, alongside a copy of the Monterey County Weekly, which features a full front-page photo of Kim Jong-un and the headline “Going Nuclear,” there is a thick stack of printer paper with handwritten markings in the margins of the text. It is Zilinskas’s latest manuscript. The book, cowritten with Philippe Mauger, examines biosecurity and biotechnology in Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

“It’s going to go to the publisher this coming week,” Zilinskas says, looking relieved and satisfied. The spark for this newest project came in 2012, when the Russian government newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta published an essay by then Prime Minister Putin, in which he stated: “What is the future preparing for us? . . . In the more distant future, weapons systems based on new physical principles (beam, geophysical, wave, genetic, psychophysical and other technology) will be developed. All this will, in addition to nuclear weapons, provide entirely new instruments for achieving political and strategic goals.”

Soon after, then Minister of Defense Anatoly Serdyukov promised to implement “the development of weapons based on new physical principles: radiation, geophysical wave, genetic, psychophysical, etc.” In August 2012, the U.S. Department of State noted that Russia has remained engaged in biological activities.

Their production of any kind of bioweapons would violate the Biological Weapons Convention, but as Zilinskas points out and as outlined in his previous book, Russia inherited the past Soviet program of offensive biological research and development. The microbial strains for potentially murderous manufactured bacteria could be reactivated for a “third generation” of biological weapons. Russia’s recent behavior, he says, indicates that such a program could already be under way.

A future with “genetic weapons” would include powerfully emergent methods, including gene editing technologies—which has shown immense promise for treating disease and strengthening the human species, but which in the wrong hands could also wipe out an entire population. This technological ability to alter organisms is progressing so rapidly that government regulators can’t keep up, and the idea of containing such research globally is an impossible goal. It is frightening to consider what would happen if terrorists used gene editing tools—which can be obtained relatively easily and at a low cost—to unleash highly lethal modified pathogens upon enemies. Zilinskas brings up a Pakistani scientist, Abdur Rauf, who had a degree in microbiology and was working to set up a bioweapons lab for al-Qaeda. Rauf had found a way to produce Bacillus anthracis.

“His notebooks fell into the hands of the CIA when the Americans came in in 2001,” Zilinskas says. “If there is a person who knows about microbiology, if he gets a colony of Bacillus anthracis, has a fermenter, is able to dry the spores . . .”

Take the Tokyo subway massacre of 1995, when the Aum Shinrikyo cult unleashed the odorless chemical weapon sarin, killing 12 people. “Anybody with good chemistry, chemists, and chemical equipment could do it,” Zilinskas says. Aum Shinrikyo “bought the precursors and they made the sarin used in the Tokyo subway, but they did also produce VX.”

If they could do it, so could other terrorists, so could North Korea, so could any smart extremist, radical, insurgent, enemy, or incendiary with the right tools.

Less than two months after the murder of Kim Jong-nam, Zilinskas began fielding messages again—this time in response to the reports of 86 people, including 28 children, who were killed in a chemical weapons attack in Syria. Hundreds more were injured, and horrific images of dying children being hosed down, and parents cradling their dead kids flooded news reports.

Authorities suspected sarin gas unleashed by the Assad regime, despite its denial of involvement and joining into the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Zilinskas saw the photos, which reminded him of Damascus in August 2014, Halabja in March 1988, victims in Auschwitz, and the Stalin purges of 1930s. Today the images are pervasive. With the Syrian attack, unlike past generations of chemical warfare, “Now you have hundreds of people with cell phones taking videos and photos,” Zilinskas says.

Before the two most recent nerve gas attacks, concerns over chemical weapons seemed to have taken a momentary back seat to nuclear weapons in the public eye. Zilinskas agrees that nuclear weapons remain of highest concern for the world’s population. But, he adds, “We probably will see more uses of chemicals by well-organized terrorist groups such as ISIS and, perhaps, Taliban, and who knows what North Korea might do beyond assassination.”

Leave a Reply