Nearly two decades ago, in the basement of the Library of Congress, an intrepid young analyst, code-named Lisa Simpson, was rocking out to Jane’s Addiction on her iPod when she made a discovery that would set in motion one of the most contentious, high-stakes dramas of the nuclear age.

About a dozen years later, two former colleagues from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) would come together, one offering the other a novelty baby onesie, to solve that nuclear crisis and bring the world one step back from the nuclear brink.

This story sounds wild because it is. It is the story of the Iran nuclear deal, told by Middlebury Institute of International Studies professor Jeffrey Lewis.

Widely known in the nuclear policy world for his pioneering podcast Arms Control Wonk, and a go-to expert for journalists covering North Korea and other nuclear proliferation hot spots, Lewis can spin a hell of a yarn. So, when the Trump administration withdrew from the Iran deal—an agreement that most experts understood as an unprecedented achievement, not just for nonproliferation but for global security writ large—he paired up with award-winning podcast producer, documentary filmmaker, and Middlebury College instructor Erin Davis to do what advocates of the deal had thus far failed to do: tell the story of one of the most important, far-reaching, hard-won nonproliferation agreements ever achieved, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA in security parlance.

The result is The Deal, an immensely enjoyable, factual, five-part narrative podcast that tells the story of the Iran deal, how it came together, how it fell apart, and what it means for the rest of us. A brilliant original score by composer Hannis Brown elevates the storytelling to mesmerizing heights.

In episode one, a young researcher follows a hunch that will change the course of history.

The Stories of the People

The story of the JCPOA begins with the tale of that research analyst, Corey Hinderstein, who essentially discovered clandestine nuclear facilities in Iran while she was toiling away in the basement of the Library of Congress back in 2002. Even the most knowledgeable nuclear wonk well versed in the JCPOA’s chapter and verse may be unfamiliar with Hinderstein’s innovative work in breaking the story to CNN. “Nobody knows this!” Lewis proclaims in an interview with Middlebury Magazine. The little-known truth, he maintains, is that “she is the one at the conference who gives [Iranian dissident Alireza] Jafarzadeh her business card, she is the one who goes into the basement of the Library of Congress and figures out where Natanz is located, she is the one who knows how to use the software to process satellite images. And she is the primary person making assessments of what she is seeing.” Today, Hinderstein—“a powerful and important person,” Lewis calls her—is a vice president at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a prestigious nongovernmental organization founded by Senator Sam Nunn and philanthropist Ted Turner.

Lewis also engages with Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz and Ambassador Wendy Sherman, two of the key U.S. officials responsible for bringing the deal to fruition. (Sherman was Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs during the negotiations and was later promoted to Acting Deputy Secretary of State.) These cameos breathe life into the urgency of the Iran problem, “which became [Sherman’s] problem,” as Lewis says on the podcast, in 2011, when her boss at the State Department, William Burns, gladly handed her the file, and the responsibility of representing the United States in the negotiations with Iran, Russia, the United Kingdom, China, France, and the European Union.

The problem had become Secretary Moniz’s, too, when Sherman relayed to him President Obama’s decision to involve him in the “political gymnastics” in 2015. Although Moniz was “a scientist, not a diplomat,” Lewis clarifies, he did have something in common with his Iranian counterpart, Ali Salehi: they were both at MIT in the 1970s, Moniz as a physics professor and Salehi as a nuclear engineering graduate student. After Salehi mentioned during their first meeting that his first granddaughter had literally been born during the meeting, Moniz arrived at their second meeting with an MIT-branded baby onesie, replete with a nerdy joke on it.

And this is where the podcast really shines: by forgoing an analyst’s usual modus operandi of spewing facts to counter falsehoods in favor of a narrative that focuses on the people who drove the story, listeners—experts and novices alike—can better appreciate the enormity of the achievement, and the consequences of its loss.

In this situation, “the least democratic actors” tend to gain the most amount of power. “And that,” Lewis adds, “tends to be the men with the guns.”

The Stories Left Untold

Of course, there are other stories that The Deal doesn’t expose. “In the end, with only five episodes available to us, we had to give up so much,” Lewis laments.

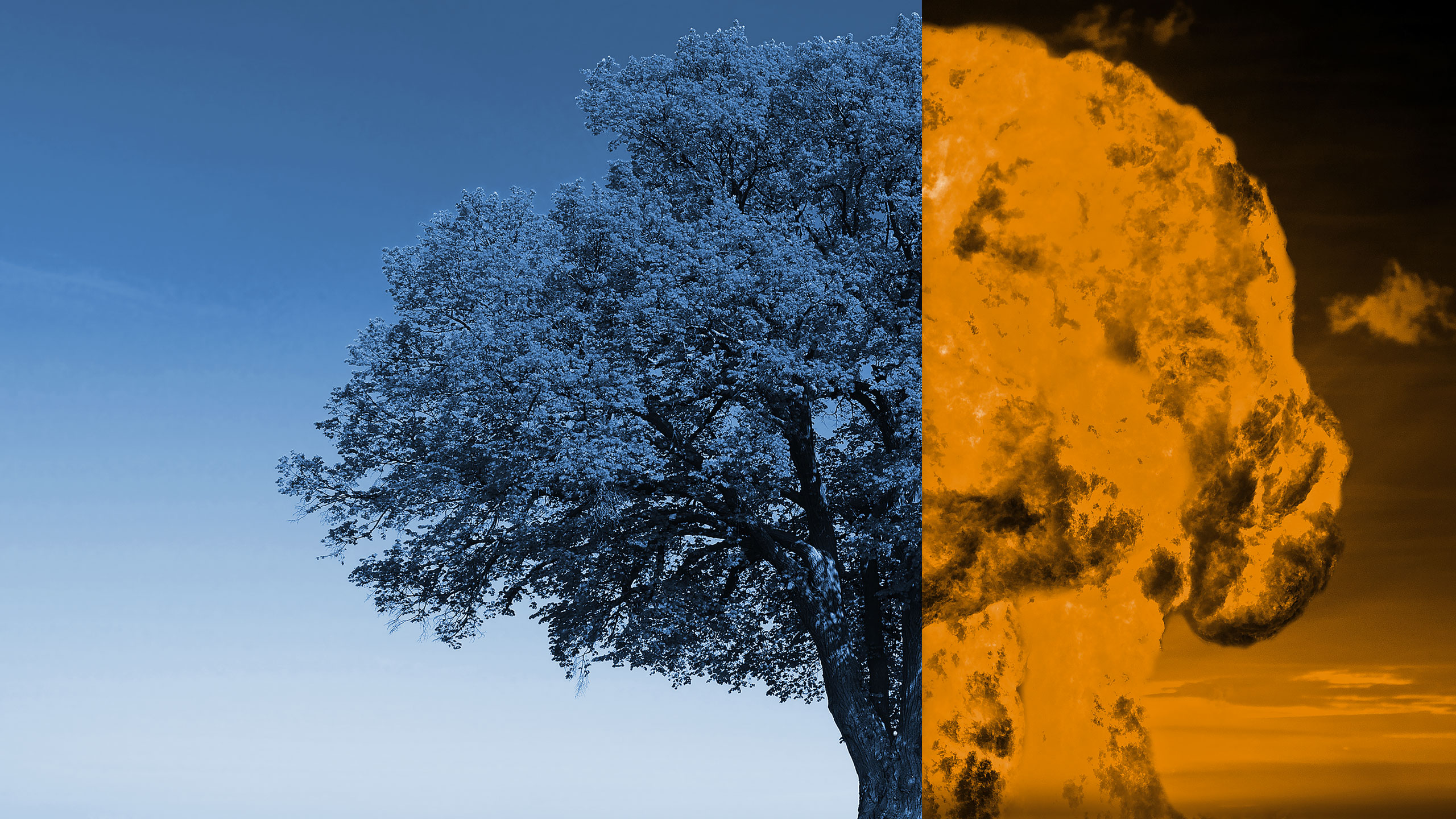

One particularly regrettable edit, he says, was the painful decision to exclude the interview they recorded with an Iranian victim of an Iraqi chemical weapon attack, during those countries’ brutal decade-long war of the 1980s. The idea behind interviewing this woman, he says, was to weave “a through-line from Hiroshima, and the hatred and racism that seemed to enable that bombing, to the present day,” when an alarmingly growing number of Americans support waging nuclear war, a focus of The Deal’s final episode. In response to these armchair nuclear warriors’ calls for “wiping out” the “barbaric” Iranians, he had hoped to hold up this “wonderful woman and her son” as the very real, very human targets of these brash, ignorant, and brutal calls for nuclear war.

Nor does the podcast explore the facilitative role of the European Union, led (again) by three different women, not men, a fact not lost on Lewis, who longs to one day make a podcast about the story of the 20th-century arms race told from the views of the women who witnessed and helped wage—or curtail—it. EU President Federica Mogherini, who served as Vice President of the European Commission, “has an incredible story!” proclaims Lewis. But excising her cameo from The Deal was just one of many powerful tales left on the proverbial cutting-room floor.

The podcast also doesn’t substantively wrestle with the precarious political highwire act that Iranian diplomats had to manage. Though Lewis does interview Dina Esfandiary, a renowned Iran expert whose noteworthy analyses offer Western audiences rare peeks into the various factions within Iran, the podcast does not deeply delve into the competing constituencies, opinions, and agendas within the Iranian government. Lewis acknowledges that constructive diplomats like Salehi and Javad Zarif—a player whom The Deal does mention at times—“took an enormous political risk to make this deal happen,” and that, most worryingly, “its collapse empowers the same people who pushed for the nuclear-weapons program in the first place.”

To Go Broad, Go Narrow

Lewis and team made a conscious decision not to address the JCPOA’s main criticisms: that it’s too narrow in scope, that it doesn’t address Iran’s missile programs, its human rights violations, or its funding of terrorism.

“It’s not that the critics are wrong,” Lewis explains. “It’s that they fundamentally misunderstand how the world works.”

The JCPOA, he says, was meant to solve a portion of the problem the U.S. has with Iran. Once nuclear weapons are verifiably off the table—something the JCPOA inarguably ensures—“it creates the space for us to go ahead and solve other problems.” He points to North Korea as a parallel example. In 1994, the Bill Clinton administration obtained a nuclear agreement with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. That deal, too, was lambasted by some for not addressing the missile program, or even its uranium enrichment program, and for focusing too narrowly on the nascent plutonium production program under way at the time.

“Once the agreement was in place a few years, the Clinton administration had a tough choice to make,” Lewis recalls. “Do you let the agreement collapse because it didn’t solve all those other problems? Or do you try to fix those other problems one by one?” The 1994 Agreed Framework, he said, was meant—like the JCPOA—to be a foundation upon which further security-enhancing measures could be added. “But then, John Bolton came along and convinced the [George W.] Bush administration to walk away from the agreement.” Like Trump after him, Bolton insisted that “a better agreement” could be reached. “Well, it’s 17 years later,” Lewis taunts, “and not only do we not have a better agreement, we have no agreement, and North Korea is parading ever-larger nuclear missiles through its streets.”

And in North Korea, as in Iran, the foreboding sense of an external threat “freezes in a kind of hostility, and it reduces the space in both countries for us to improve the situation, and it increases the risk that we fall into a conflict.” In this situation, “the least democratic actors” tend to gain the most amount of power. “And that,” Lewis adds, “tends to be the men with the guns.”

And this includes the men who want ever better, more powerful weapons, all the way to the literal nuclear option.

A Choice

In the end, The Deal isn’t just about an agreement between the United States, Iran, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, and the European Union. It’s a story about—and for—regular people facing a continuous barrage of disinformation, politically motivated attacks, and steroidal hyperpartisanship in an increasingly unstable world, and what can be done about it.

This metastasizing contagion of conspiracy theories, Lewis insists, is not new to 2020, even if it feels like it. He reminds us that the Cold War, too, was often waged through comparably tenacious disinformation campaigns, often conducted, or at least supported, by Moscow. Whether it was the claim that HIV/AIDS was originally an American biological weapon, or that the CIA invented crack cocaine to erode the African American population, “there was always an active effort by Moscow to push this information into the public domain.” The difference with today’s notoriety in this sphere is that “it is just so much easier to communicate” today, and that the speed and regularity with which we are bombarded by lies and conspiracies heighten “our awareness of it,” says Lewis. Whether truth will eventually triumph over insanity, “I’m pretty skeptical,” Lewis confesses. “But if the problem of disinformation is a problem with us, then as human beings, we have to make a choice: do you say, ‘I can’t do anything,’ or do you try to make something better?”

In its essence, then, this podcast is for “anyone who is fundamentally concerned with how we can reduce the number of nuclear weapons in the world,” Lewis says. First, we must understand that nuclear weapons, for all their worth in our current system of international relations, are simply too dangerous to live with in perpetuity. Our challenge then, he asserts, “isn’t designing a disarmament scheme that works. The challenge is designing another system of security,” one that doesn’t rely on planetary annihilation as a last—but increasingly plausible—resort.

Rhianna Tyson Kreger is the managing editor of The Nonproliferation Review, which is published by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute.

You can subscribe to The Deal at Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or Spotify.

Leave a Reply