On June 3, 2017, Alex Honnold became the first person to climb El Capitan without ropes. Carrying only a chalk bag, the 33-year-old Californian scaled the sheer face of Yosemite’s most imposing granite wall in just under four hours. Mark Synnott ’93, a journalist and fellow climber assigned to cover the historic feat for National Geographic, watched in terror through a telescope.

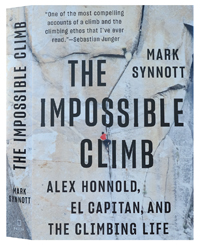

The story of that dramatic ascent forms the climax of Synnott’s new book, The Impossible Climb: Alex Honnold, El Capitan, and the Climbing Life. But this vivid, authoritative account is about so much more than that. Part memoir, part history, and part adventure travelogue, The Impossible Climb is an intimate, sometimes harrowing, examination of rock climbing through the ages and of the quirky, obsessed souls who lived—and often died—to be the first to reach the top.

Synnott clearly feels their compulsion. As a boy, he embraced “risk taking as an existential salve,” he writes, after his father told him he would become nothing more than “worm food” when he died. He shimmied up drain pipes and goaded his buddies into dancing atop snow-covered roofs and pole-vaulting across icy rivers. When he discovered rock climbing, it seemed an obvious outlet for his thrill seeking.

At Middlebury, Synnott hung a climbing rope in his dorm room doorway, winning the notice of John Climaco ’91, who introduced him to ice climbing and mountaineering. Synnott was hooked. When his dad, a banker, asked him what he planned to do with his philosophy degree after college, Synnott replied, “I’ve decided not to have a career.”

In fact, he has enjoyed an accomplished career as a professional rock climber and guide. Sponsored by the North Face, among others,

Synnott has undertaken expeditions in remote locales from Borneo to Greenland, often writing about them in heart-stopping detail for magazines like Outside, Climbing, and Men’s Journal.

When he first began trekking with Honnold in 2009, Synnott found him to be a cocky daredevil who scoffed at wearing a helmet and disparagingly called Synnott “Mr. Safety.” But they bonded over literature and philosophy, and Synnott came to see himself as one who could push the brash young climber to understand his motives and the limits of his risk taking. Was he climbing El Cap for himself, or for his fans? And how did having an audience—which included the filmmakers Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi, who won an Oscar for their documentary Free Solo—shape his experience, the nature of the climb, and his odds of success? Synnott’s willingness to explore such questions elevates The Impossible Climb from a thrilling adventure story to a meditation on how we give our lives meaning.

Leave a Reply