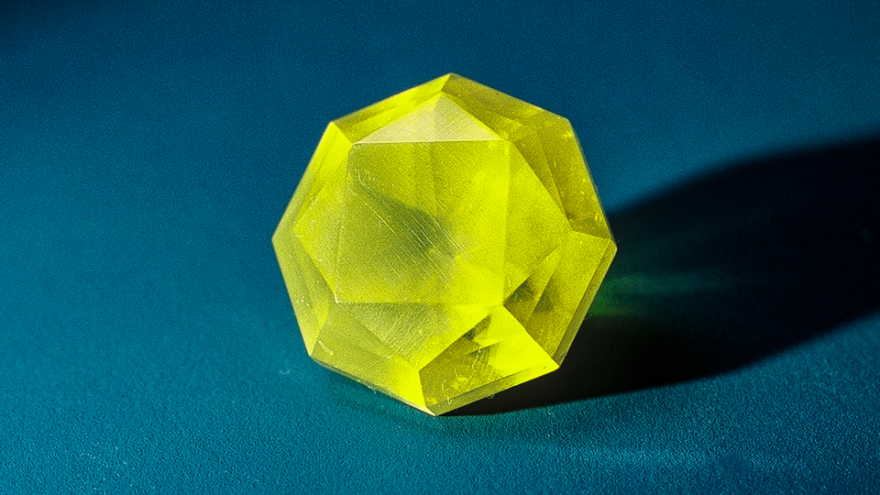

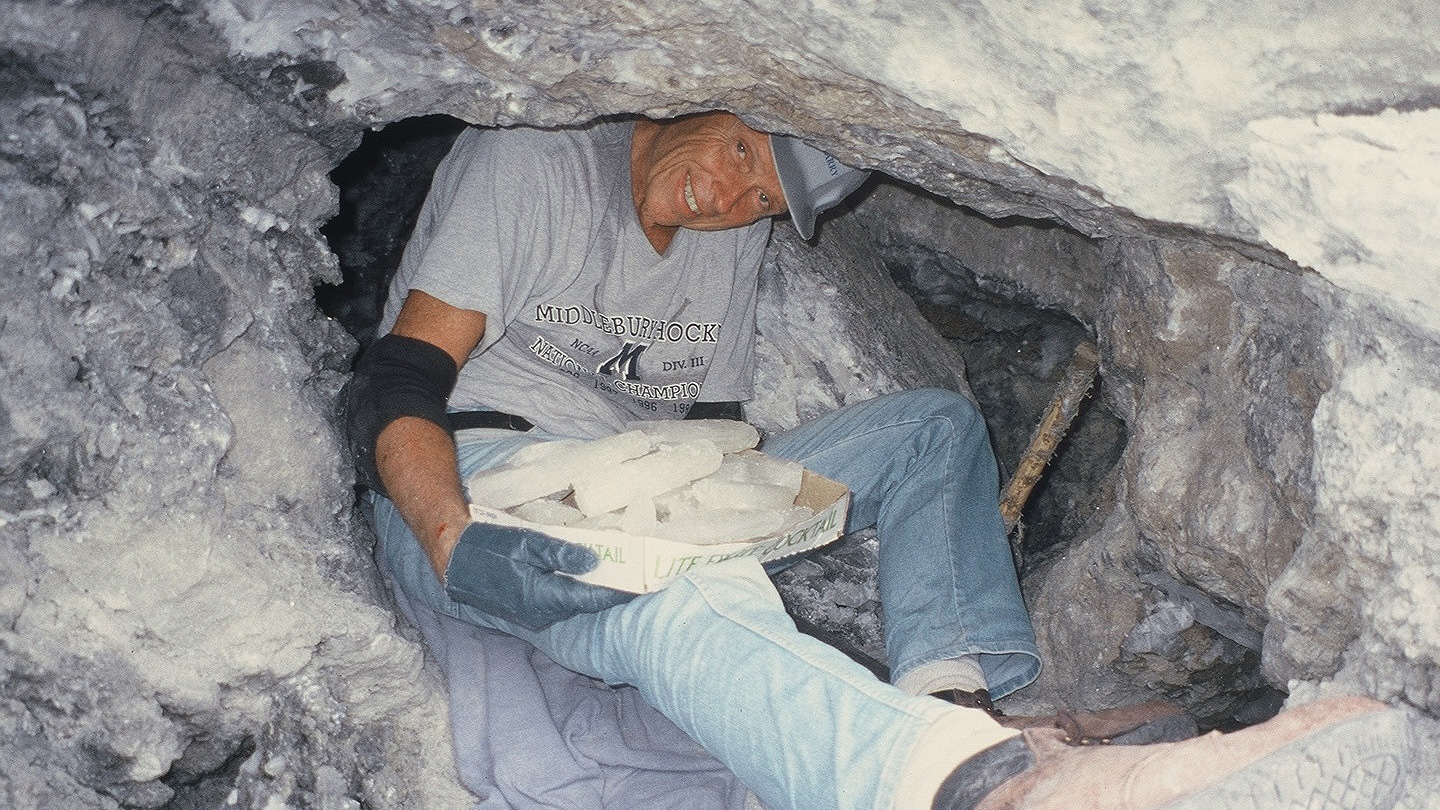

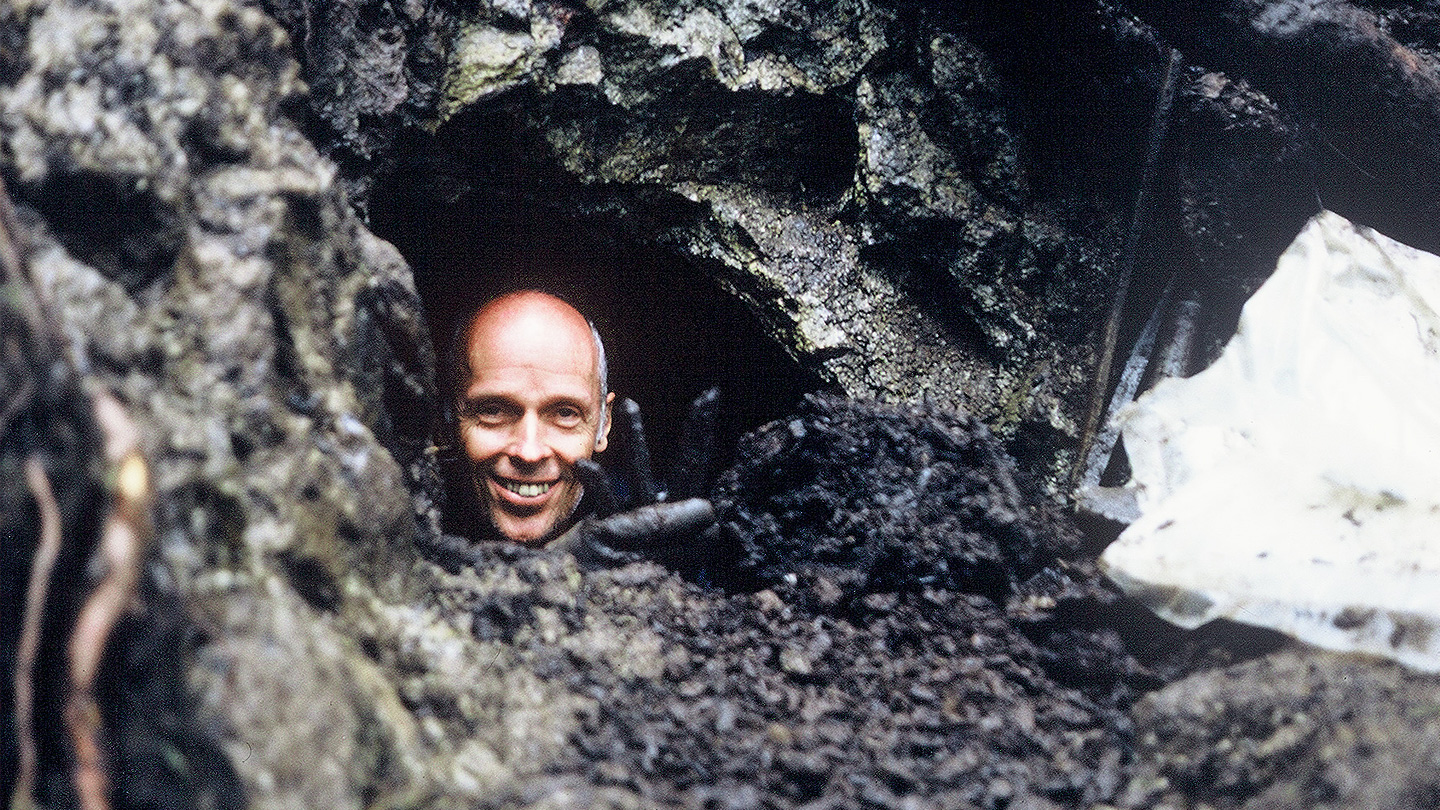

John Medici ’59 had heard that smoky quartz had been found on Sierra Blanca Peak in New Mexico, so in September 1991, he and his three sons headed up the trail of the almost 12,000-foot-high mountain. At 10,500 feet, they split up and began to explore. John and son Eric moved to a lower point on the ridge where some trees were growing on rock surfaces. Thinking the area looked too sparse to produce such big trees, both John and Eric felt that maybe it indicated a collapsed pocket of crystals nearby. They began to dig between the rocks and before long had unearthed crystals, and then more crystals, as they continued into a refrigerator-sized chamber that held the root systems for the trees. John and the three boys collected crystals for three rainy days and hiked out with eight backpacks full, leaving many specimens along the trail for other collectors.

John has been collecting minerals since 1963. Although he never took a formal course in geology or mineralogy, he first became interested in geology as a boy in Montvale, New Jersey, where the glacial debris in fields near his home held minerals and fossils that intrigued him and filled his pockets. His mother encouraged his interests by taking him into New York City to the American Museum of Natural History, where he requested the gem room exhibit every trip. He carried that interest to Middlebury, but an aptitude test he took upon arriving indicated he should go the engineering route with the Midd/MIT 3-year/2-year plan. That didn’t interest him, but he did feel that a geology major might limit his options in the future. “So I switched the original geology major to chemistry to allow for directional changes if needed,” he says. Between his years at Middlebury and then grad school at Rutgers and a PhD in biochemistry, his return to geology didn’t happen right away. He took a job with the U.S. Space Program in Baltimore, working in extraterrestrial life detection and providing nutritional support for planned Voyager missions to Mars at the time. After three years, he joined Chemical Abstracts Service in Columbus, Ohio, and spent 40 years as an editor and translator of patent and journal literature.

But along the way his interest in collecting minerals resurfaced and he found the time to get out in the field and learn the best way to pursue his hobby. “One can learn what to look for by observing displays of the desired specimens—in museums, shows, other collectors’ collections. Other collectors’ descriptions are especially helpful since the objects searched for may not look the same in the field as they do when cleaned,” John says.

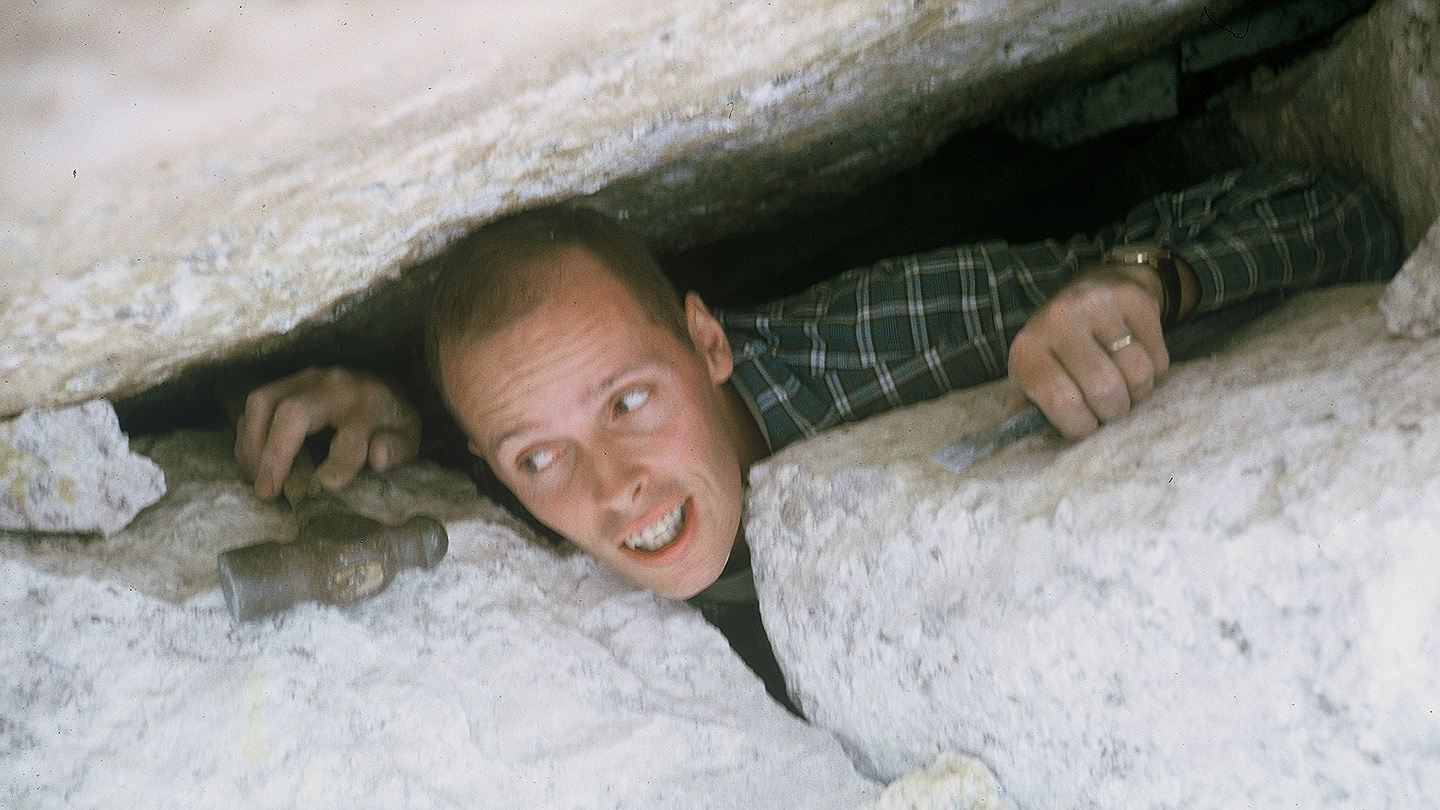

Early searches solidified his excitement. He found turquoise crystals in Lynch Station, Virginia, and was part of a crew that found the mineral apophyllite in a 60-foot prehnite tube in a fault in the Fairfax quarry in Centreville, Virginia. “Rock falls due to the fault periodically exposed more of the tube and several of us collected on and off for five months.” They attached a 100-foot rope to a road post at the top of the quarry and lowered it to the bottom, then used it to get about 15 feet up the side to the tube area. A Smithsonian curator at the time considered that find one the three best of the 1960s.

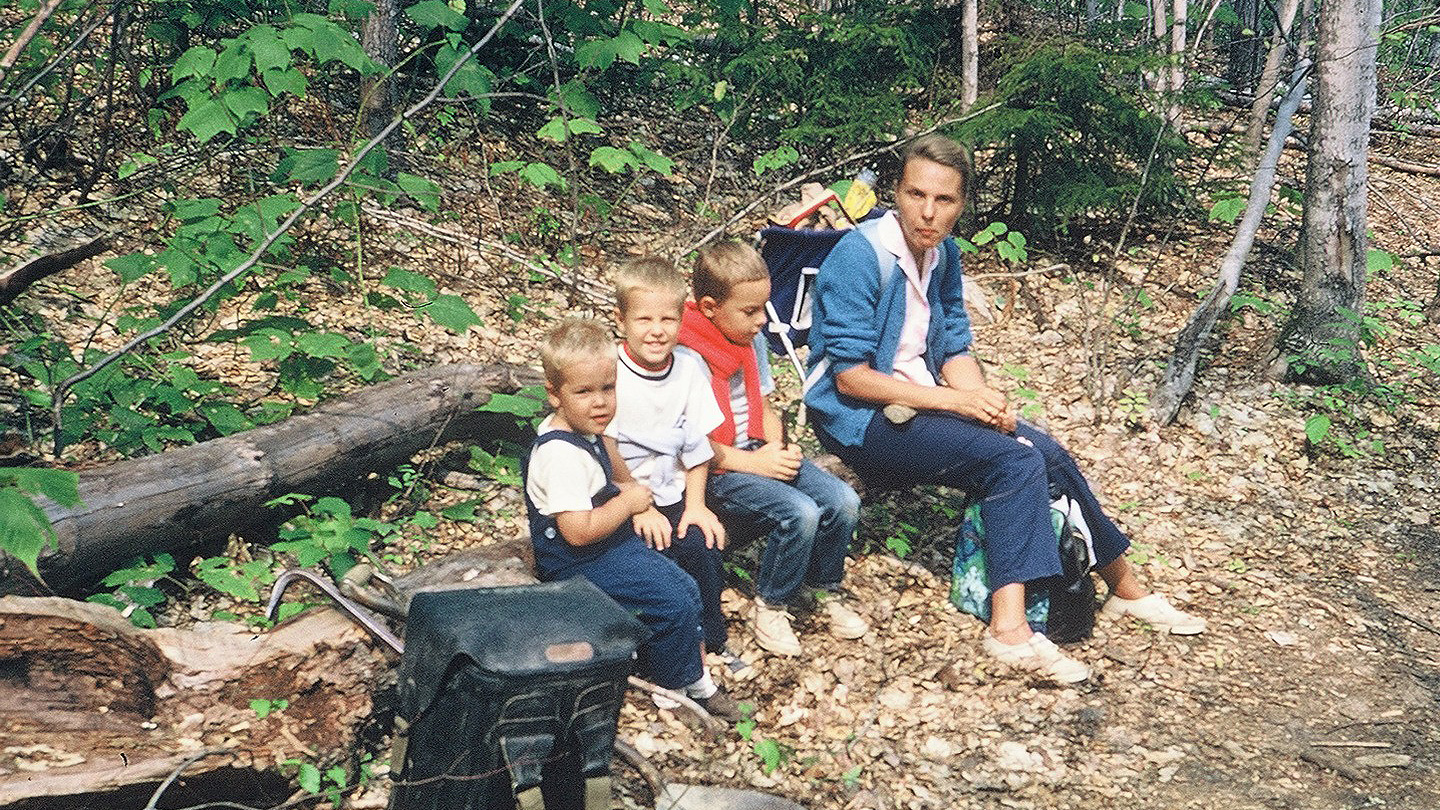

John’s sons became enthusiastic collecting partners early on. “My wife and I took our sons with us on most mineral and fossil hunting trips from the time they were able to walk. Excursions like marine fossil hunting in the Chesapeake Bay area when we lived in Baltimore or visits to quarries were great fun for them.” All three sons are advanced collectors now and often join John in the field.

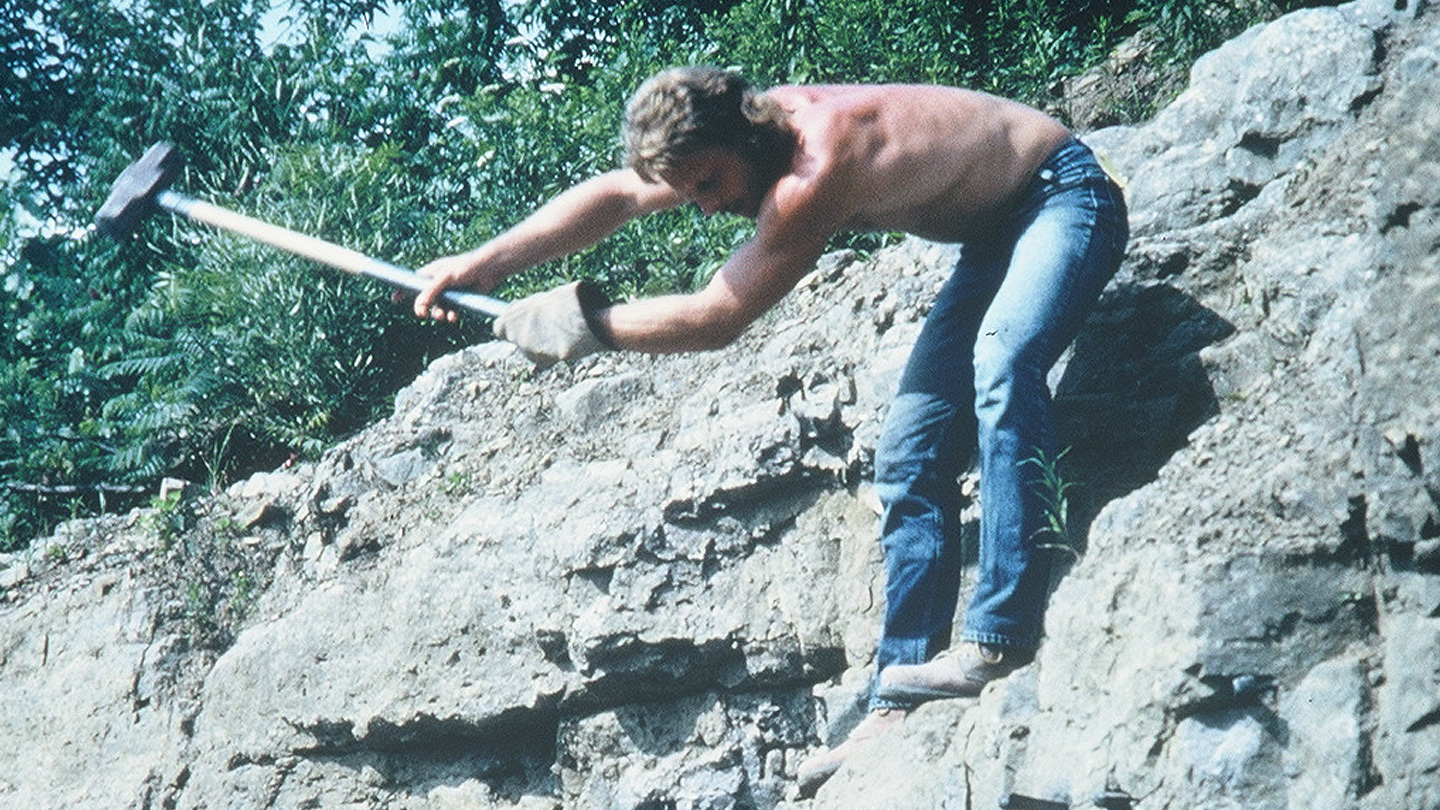

The largest specimen John and his sons have ever extracted is a 900-pound New York quartz pocket that the curator of the Smithsonian asked them to look for in 1986. The owner of the property wouldn’t allow them to use any mechanized equipment, so using wedges, hammers, and chisels, they lifted large sections of rock wall to get at the quartz and hacked the 900 pounds out in pieces, painstakingly labeling each section with yellow pens similar to what loggers and stonemasons use. Matching the numbers and letters between pieces and using characteristics such as colors and layers of colors, they slowly reassembled the specimen with epoxy to hold it together. It ended up as an island display at the Smithsonian.

Access to collecting sites and ability to extract and carry out samples varies. Some places have open access, some require permission, some owners charge fees. Ownership of the materials found depends on the location. One layer of limestone/dolomite containing quartz crystals in Ontario, Canada, was deep in a quarry where John collected from it and kept what he found with the manager’s permission. A mile away the layer comes to the surface on private land, and he had to share what he found with the owner. Some Native American–owned lands or parks out west have rules or don’t allow collecting. It’s all a matter of finding out what type of land one is collecting from. In the case of the smoky quartz in New Mexico, John had checked the land boundaries and felt there was no problem keeping the quartz.

Collecting minerals has not been without its adventures. In 1978, on the way to a collection site, John and son Jay were in a helicopter crash at the edge of Chetwoot Lake in Washington State. The gas line severed, burning right above John’s head, and there was a mad scramble to get out of the helicopter. Watching the magnesium engine burning up was a spectacular sight after which they had to sleep under the stars before making a long hike out to civilization.

But, for the most part, the trips John has taken over the years to collect have been productive and stimulating. And early on, he began to share his successful collection stories by writing articles and providing photos for various magazines and journals, like Rocks & Minerals and Mineralogical Record, as well as lecturing as the featured speaker at numerous mineral symposia. He has also donated many specimens to museums over the years and at one time owned a mineral, Inuit carving, and jewelry shop called What on Earth.

A few years ago, he was inducted into the Rockhound Hall of Fame. And last December, he was notified that he had won a prestigious award—the Carnegie Mineralogical Award for 2020 given by the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and usually bestowed on museum curators, full-time professors, and professional dealers. He was justifiably proud and honored when Assistant Curator Travis Olds said, “His contribution to the mineral community has been significant, but his greatest contribution to specimen mineralogy is his dogged pursuit of top-quality specimens in the field, specimens that would otherwise be destroyed by industry or nature.”

Leave a Reply