The darkroom at Telluride High School was a sanctuary for Esme Fahnestock, now a sophomore at Middlebury. Inside, it was pitch-black and peaceful, a realm in direct contrast to the fluorescently lit classrooms and bustling hallways that existed on the other side of the door. During this time, Fahnestock was a darkroom devotee. When she was 15, she had discovered her father’s old Nikon film camera buried away in the attic, and subsequently signed up for a photography class at school to learn how to use it. After taking the class, the darkroom became her high school hideaway. Whenever she could—before school, after school, during free periods or lunch—she ventured to this space, locked the door behind her, and exhaled.

“It turned into my space,” Fahnestock says. She liked being surrounded by a mess of chemicals, papers, UV filters, all waiting to serve as ingredients in her uninhibited experiments. Like when she smeared the developer onto her images with a paintbrush to see what would happen.

“It was easy to go in there and get lost, and not realize three hours had gone by,” she says.

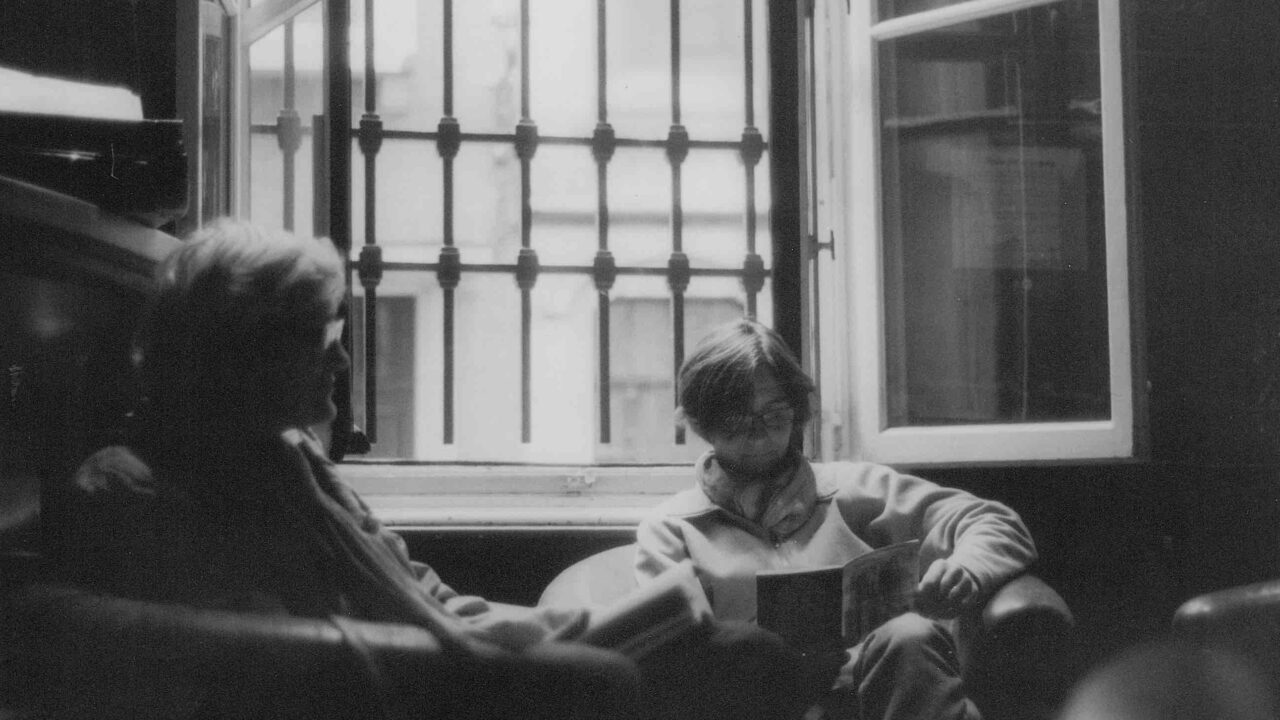

When Fahnestock arrived at Middlebury, she went in search of the student darkroom; there, she discovered that the smells and archetypal objects scattered around the room were instantly familiar and eased her transition to a college far from home. On a Sunday afternoon last March, in between homework and slow dining hall meals with friends, Fahnestock and I met up at the darkroom to explore the space.

Middlebury’s student darkroom is tucked away, just past the industrial laundry room in the basement of Forest Hall. Fahnestock led me into a small, dimly lit room dominated by a steel countertop, upon which were strewn some old photo developing tanks and film reels. On the left and right walls, though, stood black revolving doors, the kind of contraptions that would look right at home in a sci-fi or fantasy movie: Enter here, and we’ll transport you to a magical realm. Which, for a photography geek, they kind of do, leading one into adjacent developing and printing rooms.

Like Fahnestock, I recently fell in love with film photography. After years of experimenting with shutter speed, aperture, and composition on my family’s digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) camera, I wanted to try and work with film. Unlike Fahnestock, I didn’t discover any antique treasures at home, so I took to social media to crowdsource an old camera.

It only took a few hours before someone responded to my posting: “In search of film camera.” The seller turned out to be a middle-aged woman who lived in my town; she had been trying to unload a Canon AE-1 for a while. After exchanging messages, I plugged her address into Google Maps the next day and drove 15 minutes to her house on a quiet cul-de-sac. I parked and made my way to her front porch, where my new “old” camera sat at the bottom of a Trader Joe’s shopping bag.

I was so excited, I picked up a battery and some film at the drugstore on the way home. Once there, I sat in front of my computer for the rest of the day, watching YouTube videos that taught me how to load film and read the light meter.

I was hooked.

Despite growing up in the digital age, Fahnestock and I are not alone in our newfound interests in film. For the last three years, companies such as Kodak, Fujifilm, and Polaroid, companies that in the early 2000s neared or even declared bankruptcy, have been experiencing growth of about 5 percent year-on-year. These companies claim that this growth is fueled by young photographers growing interested in film, a claim seemingly confirmed by a 2014 study by Ilford Photo, a U.K.-based company known for its black-and-white film. Among the findings of the Ilford survey: nearly a third of the photographers who use film are younger than 35 years old. Kodak, for one, is paying attention. After discontinuing its popular Ektachrome color reversal film in 2012, Kodak resurrected the product in 2018. “Darkroom photography is making a comeback,” said Kodak President Dennis Olbrich, after a previously discontinued black-and-white film, the T-Max 2300, hit stores in March of 2018.

I’m thrilled, of course, but skeptical.

We live in a world in which nearly all images are produced by automated settings on machines and are easily edited through Instagram filters or manipulated in Photoshop. Recently, Google took automation one step further when it started selling Google Clips, a small camera that uses artificial intelligence and machine learning to take seven-second recordings of subjects that it finds interesting. Just plop the two-square-inch device on your countertop, and it starts documenting—no human effort necessary.

So, are digital natives like me truly turning away, even slightly, from this hyperautomated world? And if so, why?

I recently read an essay by the writer Rebecca Solnit that might provide some answers. In “We’re Breaking Up: Noncommunications in the Silicon Age,” a piece included in Solnit’s 2015 book, Encyclopedia of Trouble and Spaciousness, she posits that human interaction changed for the worse with the advent of technologies that claimed to make our lives easier.

“Young people are disappearing down the rabbit hole of total immersion in the networked world—and struggling to get out of it,” she writes.

Technology often promises to connect us, but as numerous psychological studies conducted in the early 2000s showed, it more often makes us feel isolated. And, more recently, a 2018 nationwide survey by insurer Cigna found that the majority of respondents said they were lonely. Many said they felt like the people around them weren’t really with them.

Trying to get out of the rabbit hole, Solnit says, is “an attempt to put the world back together again, in its materials, but also its time and labor.”

It seems that by shooting film, digital natives like me are demonstrating a yearning for connection, staging a rebellion of sorts against the immense forces of technological advancement.

To better understand what I like about film photography, I found it helped to learn more about the history of the medium. Photography arose alongside the steam engine and the telegraph in the rapidly developing European cities of the Industrial Revolution. Artists had long been fascinated by the transformation of light and image projection, often building camera obscuras, Latin for “dark room cameras.” These devices projected inverted outside scenes through pinholes onto screens or walls. Amateurs experimented with camera obscura and other image-manipulation techniques, and later attempted to capture these results permanently. (It wasn’t until Frenchman Louis Daguerre’s announcement of his daguerreotype process in 1839, which printed unique images on a copper plate polished with silver, that practical photography was born. The mirrored silver-coated plates were sensitized to the light and placed in a camera obscura, and the images were developed after contact with vaporized mercury.) Unlike the art of painting, photography preserved the past with accuracy; it obliterated our previous conceptions of time and space. Solnit, in her book about early photographer Eadweard Muybridge, writes about this, too: “Photography arose out of the desire to fix the two-dimensional image that the camera obscura created from the visible world, to hold onto light and shadow.” And like other technologies that emerged during the bustling period of industrialization, photography spread in popularity and rapidly cycled through new advancements until, as Solnit writes, the “art of hand had been replaced by the machine of the camera.”

And this distresses people like Michelle Leftheris, an assistant professor of studio art at Middlebury.

“Photography is in crisis,” she says.

We are sitting in her barren office in the Johnson Memorial Building, and she is bemoaning the state of her field. Photographers have lost control in taking and curating photographs, she says, and they have given up that power to Instagram algorithms, preset filters, and small machines that determine what is interesting or beautiful.

Leftheris began teaching photography at Middlebury in the fall of 2017, and before that she taught at the School of Visual Arts, an art and design college in Manhattan. Before she arrived on campus, she looked over the course offerings and assumed that Origins of Photography: Shooting Film would be a one-time effort due to a lack of student interest. Much to her surprise (and delight), though, she discovered that the course was full and even had a fully occupied waitlist. Her new colleagues told her this was a recent phenomenon; just a few years back, there was scant demand for a course in film photography.

And the interest has not waned. During the past two fall semesters, the course has filled up quickly. And because of student demand, Leftheris says all of her new purchase requests of the College for this academic year, such as cameras and other equipment, had to do with film, versus digital, photography.

“It’s funny that in 2018, we’re going back to analog,” she says.

Since being at Middlebury, Leftheris, a professional photographer, has turned back to film photography herself. When she was 12 years old, her step-grandfather gave her her first camera, also a Canon AE-1. She says she found film to be magical, a word choice many have used to describe the medium, but then the excitement of the digital age—the quick shots, the endless opportunities to capture moments multiple times within seconds, the instant gratification—grasped her, too. “Digital was the perfect medium for the frantic and heart-pumping pace of New York City,” Leftheris says, which is where she found herself after college.

But the excitement for film that Leftheris found in her students at Middlebury prompted her to turn back to her old film cameras, and she has found the switch to be revelatory. “All of the things that I used to take for granted with film photography—the way it captures the right light, for example—came rushing back to me as I photographed my daughter,” Leftheris says. Now, documenting her friends and family happens pretty much all on film.

Through her reentry to the world of film, Leftheris has developed a theory for why film photography resonates with her students and other young people. At first she wrote off her students’ interest in film as a desire for nostalgic art forms. But now she thinks it is more about the process.

“We are so removed from the process of things,” she says, “that we stay at a distance, letting technology take over the work of creation that we once undertook ourselves.”

To take photographs with a film camera, you have to understand how a camera functions. You have to understand light and how to capture it. You have to understand the shutter speed, the alignment to get the focus just right, what depth of field you want for a given subject. You have to pay attention; you have to be involved.

I recently spoke with Katherine Lee, a fine art analog photographer and instructor at George Washington University’s Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, and she told me that her students are fixated by these analog devices, solid clunky things that bear little resemblance to the flat, sleek design of the digital gadgets they know. “They’re not exposed to many mechanized machines,” Lee says, which is why she gives the kids a specific time during each class to play with the equipment.

Lee also instructs elementary school students as young as five in darkroom photography, and these kids, she learned, could play with film cameras for hours.

“They open and close things, smash buttons, twist handles,” Lee says.

Lee thinks that while her young students’ behavior might correspond with the playfulness of their ages, she’s witnessed the same tendency—the desire to be physically part of the analog photography process—in her older students when they spend hours in the darkroom.

“Things that require attention and problem solving,” she says, “bring a lot of enjoyment to people.”

One day last year, I joined Leftheris in the Johnson darkroom. The door masked all noise and light, preserving an uninterrupted darkness. I found the atmosphere to be meditative.

We mixed the Kodak Professional D-76 developer, made of mostly sodium sulfite powder, with water in a large rust-brown tank. Next, we filled graduated cylinders with fixer, a solution to stabilize the images, and two water rinses to remove the exhausted chemicals from the emulsion. Performing our chemistry experiment, we submerged the film in all of the liquids, and then put it in the drying chamber.

After the film dried, an amber light revealed the photo negatives. We didn’t speak; the only sound, save for our breathing, was that of water filling a tank.

“Watching the images slowly appear in a bath of chemicals is like reliving the moment that you captured all over again,” I remembered Fahnestock telling me.

I found affirmation in that moment—here were splashes of light and shadows that had first been absorbed by my eyes, then by negatives, and, eventually, paper. It meant that a memory had actually happened.

I was thinking about this experience one Saturday last spring as I prepared for an excursion to Hurricane Mountain in the Adirondacks with three of my friends. My Canon had been sitting on the shelf above my desk in Lang Hall for a few months, unused, but as I thought about this trip, I decided to bring it with me instead of relying on my iPhone. So early that Saturday morning, I put on my warm layers and snow boots, replaced the contents of my backpack (notebooks and a laptop) with jackets and MICROspikes—and grabbed my camera and a new roll of black-and-white ISO 400 film.

In the Adirondacks, we discovered that the trail was blanketed in a new layer of spring snow, several inches deep; the trees became increasingly coated in white as we got higher, the snow masking their trunks and branches. About halfway up, we reached a clearing. As I took out my camera, I thought of Fahnestock and what she had told me the first time she rhapsodized about film to me.

“When you take a picture,” she said, “you are literally capturing light onto a piece of film. It’s like you are actually taking a little, physical piece or representation of a real moment in time. It’s just so cool.”

I removed my camera’s lens cap and pointed toward the crowd of trees below. Just then I heard three robins singing to each other and noticed them flitting from branch to branch. I adjusted my focus and waited patiently for one of the robins to alight on a branch, and when one did so, I pressed down on the shutter button. A loud clicking sound indicated the quick opening and closing of the shutter. And in that 1/30 of a second, I captured the winter Adirondack light on my film, a physical representation of the moment on Hurricane Mountain that I took back home with me to Middlebury.

Leave a Reply