W hen I was Gregg’s student I didn’t know his son had just died. Maybe that’s why he brought us snacks to class. I remember the orange slices.

Gregg Humphrey ’70 was my first teacher at Middlebury. Gregg was a former hippie and elementary school principal, with an antiauthoritarian attitude and a Santa Claus resemblance. He was the perfect welcome to college.

At the end of my first East Coast autumn, as the leaves were dead and dry, and the air was starting to smell cold, our class gathered at his house to organize his woodpile. In assembly line formation, we swiveled our torsos and passed the wood from arm to arm, stacking it in his garage for the winter months.

There in the driveway, with an armful of wood, I met Gregg’s wife, Susan. She worked at the bookstore and at the food co-op, and she was also a Middlebury graduate (Class of 1974), a former teacher, and an avid gardener. After the wood stacking, they served us a meal on the theme of “the color orange.”

Did I know their son had just died? Well, thinking back, I knew he had died, but I didn’t realize he had just died. It seemed like a distant thing to me, the way teachers’ pasts often blur into ancient history. I had a vague sense that Gregg and Susan had lost their son, but Gregg was so cheery, always bringing orange slices to class. How could he be sad?

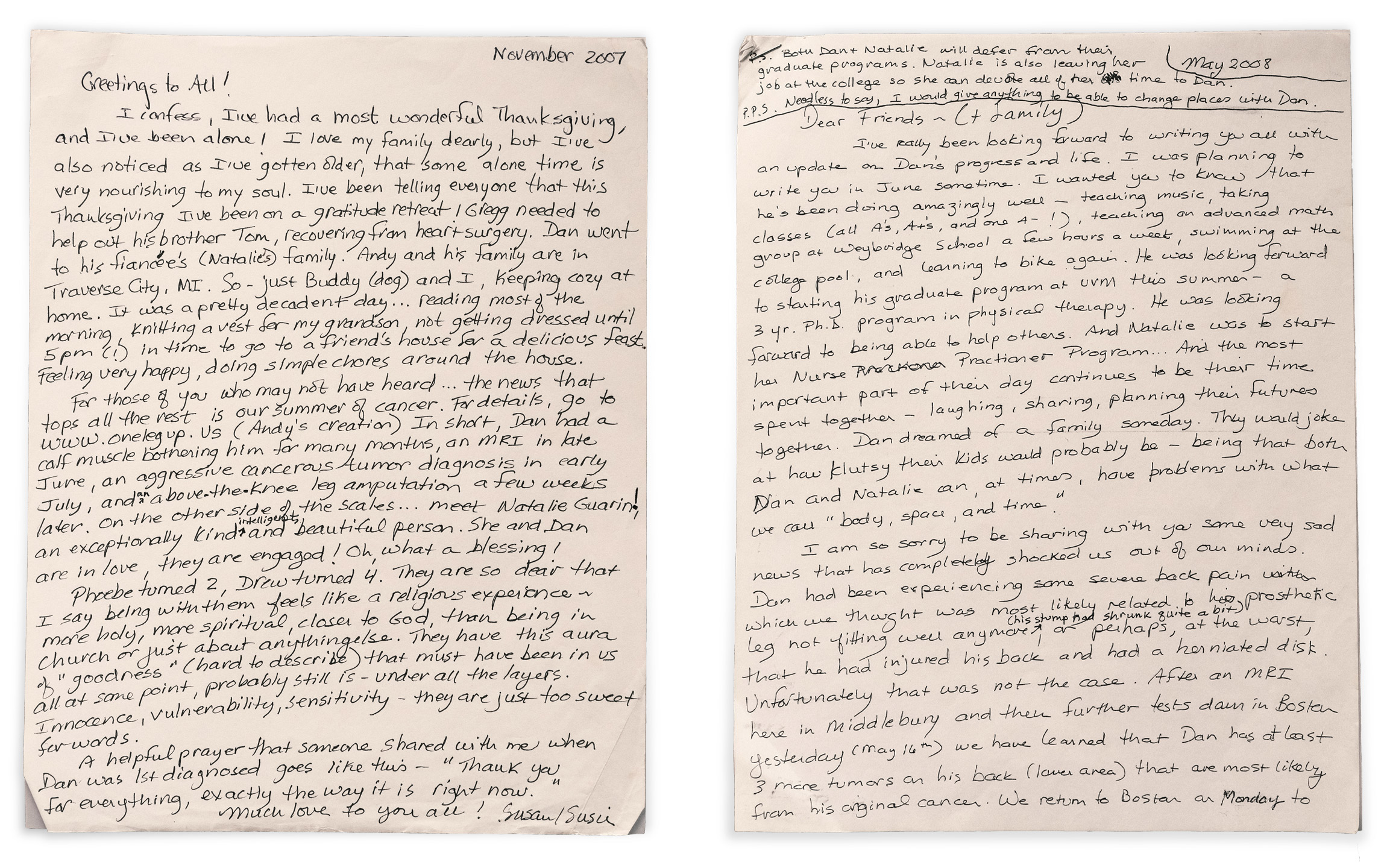

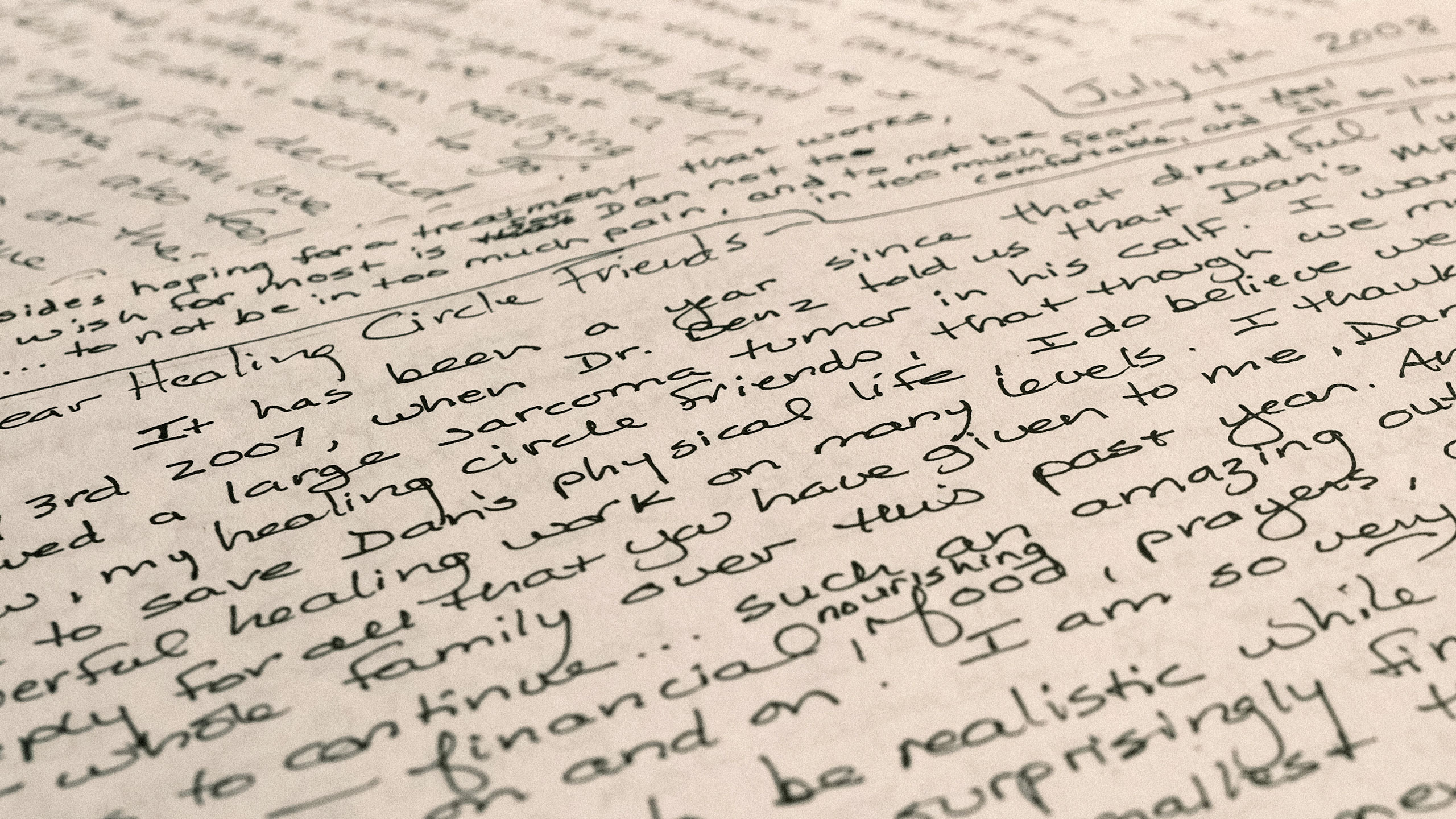

Shortly after I left college, Susan hired me to transcribe a stack of handwritten letters that she had sent to her friends after their son’s cancer diagnosis, that she was now hoping to turn into a book. The letters began in 2007, when their son, Dan, was 24 years old. It was then that I realized Dan had died just a month before I met Susan and Gregg.

Transcribing her letters was a powerful experience. To feel someone else’s words pass through your fingers plays tricks on your mind, and you fleetingly feel as though you are that person. It was then that the reality of their son’s death, and how shortly it had occurred before I met them, finally hit me.

Through her letters, I relived Susan’s experience of losing her son, in real time—from the uncertainty of the diagnosis to the sinking realization that he would die. The letters began with Dan’s diagnosis in 2007, continued through his death right before I began college in 2009, and carried on until 2017. I recall being on an airplane, already closer to tears than usual because of whatever planes do to you, when I opened up the first letter and began typing:

Dear Co-Op Friends and Bookshop friends,

Just checking in . . . a few of you have mentioned that you really like hearing from me. I’ll try to keep you posted from time to time . . . We’re all holding up as best as we can, each in our own way. We are totally on some kind of journey—it’s all unknown. One day at a time, as they say. I know when Dan feels increased pain, or pain in a new area, it brings up fear. I think that’s one thing I hope the most for—that Dan not be in too much fear. Maybe that’s where all the love will come in . . . to soothe the fear . . .

Love,

Susan

Dan Humphrey was a snowboard instructor at the Middlebury College Snow Bowl when he felt a pain in his calf. Assuming it was a ski injury, he began attending physical therapy, but the pain remained. And then, he was out mowing the lawn when he collapsed from excruciating pain in his calf. At the emergency room he received an X-ray and was sent home with some crutches. It was weeks later, after returning for an MRI, that they received the call from an orthopedist. It was cancer of the tissue; a form of cancer so rare, the doctor said, that the chances of contracting it were equal to being struck by lightning twice.

At just 24 years old, Dan had his leg amputated. Susan held a healing circle with her friends, and a few weeks later she wrote to say the surgery had been successful. “Dan’s spirits are good,” she told them, “though at times he’s in quite a bit of pain and has sad moments.”

For nearly a year, things were fine. Dan was learning how to resume his life with a prosthetic leg and began gravitating toward his bike again. But that spring, he felt severe back pain. An MRI revealed that his cancer had returned in the form of multiple back tumors, and the type of cancer was incurable. Radiation and chemo could shrink the tumors, but they would be nearly impossible to eradicate. On the ride home from the doctor’s visit that revealed the news, Susan remembered Dan cuddling with his partner, Natalie, in the back seat. Natalie and Dan had met in Middlebury, when she had just graduated from the College and he was working in the produce department at the co-op. Now they had been dating three years, and she was a nurturing presence, caring tenderly for him when he was in pain.

Susan drafted another letter to her friends and family to tell them the news. I’ve heavily edited these letters for brevity, and the following letters are excerpts of what she wrote:

May 2008

Dear Friends and Family,

I’ve really been looking forward to writing you all with an update on Dan’s progress and life . . .

He was looking forward to starting his graduate program at UVM this summer—a three-year PhD program in physical therapy. . . . And Natalie was to start her nurse practitioner program.

I am so sorry to be sharing with you some very sad news that has shocked us out of our minds.

After an MRI here in Middlebury and then further tests down in Boston yesterday (May 16) we have learned that Dan has at least three more tumors in his lower back that are most likely from his original cancer . . .

It is not curable.

We don’t really know how much time he is likely to have.

I feel certain that Dan and Natalie have been together before in a past life, and that they will indeed find each other again in some future life.

This will most likely be the hardest thing I go through in my lifetime. In deepest sorrow, I am your friend,

Susan/Susie

PPS: Needless to say, I would give anything to be able to change places with Dan.

Susan’s book of these letters, The Path to Fernglade,was published in May of last year. The letters are held together by additional stories, poems, and commentary on the experience of losing Dan. Of the 25 letters she wrote, most were handwritten, photocopied, and mailed to a group of about 30 friends and family members.

Susan learned the art of letter writing around the age of 10, when her family lived in Tobago, West Indies, and she attended an English boarding school on the island of Barbados. Stranded on an island with no phone line, she used handwritten letters as her primary emotional support, and she said that in some ways, she felt that her “very survival depended on it.”

During Dan’s illness, she felt drawn back into the practice of letter writing. She tended to write when she felt like it, all in one sitting, with no prior planning. Writing for an audience was both a coping mechanism and a comfort, and she slipped naturally into the role of “witness-observer.” Her main subject was Dan, of course, but she also noted the radiologist “tinged with a graceful sadness,” and a priest with a “presence and a rich, sonorous voice.”

She was at her best, however, when she turned this quality of attention back toward herself. At first the task ahead of her was so monumental she approached it with curiosity, even felt that it was a calling. When it became clear that he wouldn’t live, her feelings emerged in plain, strong sentences: “I was angry that Dan was dying.”

July 2008

Sometimes I am just surprisingly fine. Dan too. Other times it just takes the smallest thought to put me in tears.

And some of the time, every now and then, I’ve even had the feeling that as awful as this situation may be (I could even call it “horrific”), sometimes I feel that all is exactly as it is meant to be. Could that be possible?

As the letters continued, she contemplated how she could gracefully usher her son toward death. In some ways, illness had returned him to an adolescent state—he needed his parents, and yet he needed to be apart from them. “I tried to be an encourager, a reminder, and at times a sweeper of the path,” she wrote later in her book.

Dan and Natalie decided to get married that summer, right as he was beginning his chemo treatments and still had some hair. Many months later, when it was clear the treatment wasn’t working, Dan and Natalie embarked on their honeymoon to the island of St. John, along with Susan and Natalie’s mother.

Part of me wanted to say to her, ‘I am here with my son Dan, who is getting a chest X-ray. He is dying of cancer and you probably won’t see him again.’ But I kept quiet.”

On this trip, Susan described drifting between the roles of mother, chauffeur, and documentarian. “I remember at one point taking a photo of Dan, looking at it on my camera screen, and wondering if it would be a good shot for his obit,” she wrote. “Yes, one could see the port on his chest where the chemo liquid was administered, but I figured we could probably crop that out.”

When they returned from their vacation, Dan’s condition became dire. At the hospital, in Middlebury, Susan took him to get a chest X-ray. “I felt between two worlds,” she wrote. She was in the waiting room when she noticed an acquaintance from town. “Part of me wanted to say to her, ‘I am here with my son Dan, who is getting a chest X-ray. He is dying of cancer and you probably won’t see him again.’ But I kept quiet.”

December 2008

Last night coming home from Boston, he said, “Merry Christmas, it’s been nice knowing you all.”

Later on he said, “Mom, what would you do if you were dying?”

Susan took the question seriously. She contemplated it, got out a pen, and again began writing.

December 2008

Dear Dan,

I hope it won’t freak you out, my writing you a letter. But if you were to die of cancer, or something else, before I die, I would be very sad if I had not written to tell you a few things. . . .

If you die before me, I want you to know that although I will miss you terribly, you will still be a very real presence in my life. I will not see you, but I will think of you every day and I will often feel you there. . . . I will probably even have conversations with you. I wish you could think of some way to give me a sign, so that I know it’s you, and that you are there. You will at times be close by, I feel sure, just behind the veil, as they say.

I hope you will not be afraid. When the time comes that I am dying, even though I’ve read quite a bit about dying, I’m sure I will still be a bit afraid. It’s natural, the fear of the unknown. But I am hoping that you are not afraid, and that is what I hope for myself, too. From what I’ve read, when we die we return to a place of great love, peace, and deep serenity.

I love you so much, Dan, and I thank you for being my son in this lifetime. You are a wonderful human being, a radiant soul, and a true blessing for our family.

When the time came to read Dan the letter, she found herself unable to do it. So she huddled in the bathroom, tears streaming down her cheeks, listening through the door as Natalie read it out loud to him.

In that final week, Susan was by his side, a benevolent observer. She took note of his back, like that of “a delicate bird with bent wings, trying to catch its breath.” Dan did crosswords, watched his favorite childhood TV show, Arthur, listened to various jazz CDs and the soundtrack to Curious George. During his final night, he dreamt he was burning in a fire. He woke up screaming, “You assholes! You assholes! You assholes! The doctors! They knew all the time. They knew!” In the hours leading up to Dan’s death, Gregg was with him and Natalie, and for posterity, he wrote the following account:

January 2009

I moved to his side, and it was then that I saw Dan reach his head up and kiss Natalie. Perhaps he put his hand up to hold her to his lips, but I’m not sure about this. This seemed an incredibly long kiss which, looking back, and now knowing that it was a kiss for eternity, may have been the actual moment that I knew he was truly dying. He was in complete control and had been, of course, for hours.

We called Susie. We did what we could to talk to him and be with him until she arrived, and the home health nurse arrived, and we got Andy on the phone, and I put his own CD on the player, and then, calmly, he died.

“We knew it was coming soon,” Susan wrote. “Yet when he died, it was absolutely shocking.”

A man named Tom arrived to take the body. “His jeans might have had a hole in the knee, and he was wearing a little ski cap very much like the one Dan used to wear,” Susan wrote. “He made himself right at home, sitting for a long time with Gregg at the kitchen table and telling some pretty good stories. He was compassionate and down to earth; best of all, he was in no hurry whatsoever.” At Tom’s suggestion, they snipped a lock of Dan’s hair and slipped a note in his pocket. Then they loaded Dan’s body into Tom’s car and watched him drive away.

January 2009

My favorite crying, I’ve decided, is the one where I’m simply overcome with love for Dan.

The cold weather served as an emotional cocoon. “Deep mid-winter seemed the perfect time to die,” she wrote. “I don’t know why that would be so, but the cold white snow, the quiet landscape, keeping cozy by the wood stove—it just felt right. And I wanted time to stand still.” She felt connected to Dan, but also to a greater, more mystical presence. She had traveled to the outer reaches of motherhood—to the rawest place of love.

March 2009

For me, Dan has pretty much become synonymous with love.

Cards came every day for a month. No Hallmark card was too cheesy, and Susan basked in the “bubble of love.” But inevitably, the river of cards slowed to a trickle. On February 23, 2009, she marked in her datebook: “The first day of no cards—Dan.” And then, the next day: “Cards Dan again.”

As the ground thawed, the halo of love around Dan’s death, and the emotional adrenaline, began to fade. “I remember being somewhat appalled when I realized people were getting on with their lives,” she wrote. “And even the seasons were being fickle; how dare winter slowly give way to spring?!”

When she did have the peace of mind to focus on something, it was the crawl spaces of her house that obsessed her.

Then, a new kind of pain crept in—not the lovely sadness of remembering Dan, but a darker, more terrifying pain. Something closer to fear. During his illness she had felt close to God, in the form of beautiful synchronicities and unexplainable coincidences. But now those moments faded away.

The letters took a sharp turn; too distraught to write at the time, she chronicled the experience in a letter, many months afterward. She said she felt that she’d encountered a second death; that when Dan died, her spirit died as well. Her loss of self was overwhelming and unnatural. Life became unbearable. When she did have the peace of mind to focus on something, it was the crawl spaces of her house that obsessed her:

What is going on down there? And how can we improve the drainage/moisture problem, the heating, etc. It mirrors my own inner house, where the shock of Dan’s dying has set things loose. Old beliefs, memories, limited vision, painful experiences/feelings . . . they’ve all gotten shaken up somehow.

Grief unlocked a sense of searching within her. Instead of missing Dan, she found that she missed her mother, and memories from her childhood began to return. In her despair, she felt needy, and her neediness felt shameful. “Somewhere in my belief system was the idea that neediness equals abandonment,” she wrote. “E.g., if you are needy, others will leave you. And I still have confusion around this.” In her letters, she recounted her pain in one particular moment:

One night, awake in bed, I felt as though I were seeing all the horror in the world at once—murders, wars, crime, confusion, people hurting one another. It felt absolutely terrifying and I prayed, saying, “Dear Lord, please forgive them, they know not what they do. . . ” That is how it seemed to me, that most people wanted to do the right thing but we were lost. That included me. I remember thinking that if I totally lose my bearings, to just remember a few simple guidelines—be kind, and treat others as you would want them to treat you. The problem seemed to be in my mind—I know I even said to myself, “My mind is killing me.”

The era of simply missing her son suddenly felt so simple; she now longed for such a time. During these months she prayed to God, and even to Dan, that she would find herself again. “I might be fine in the morning, and then at a certain time in the afternoon I’d feel it coming on,” she said. For a year, she barely slept. She visited a naturopath, and visited a sleep clinic. Finally, during her annual physical, her doctor prescribed Zoloft.

I thought maybe I was feeling a little better; then on March 21, the first day of spring (?), I knew something was really different. I just felt solidly here. It is hard to describe . . .

What I especially noticed was that the hypercritical voices that seemed like they were almost trying to kill me simply stopped. I couldn’t even remember the bad things they were saying about me. The sense of relief, and release, from such relentless self-criticism was quite extraordinary.

“The only negative reaction to the Zoloft was that I couldn’t cry,” she told me. “But I was fine with that.”

So the path to recovery began. First, she felt a deep appreciation for her sanity, and every simple household activity felt blessed. That year she turned 60, and life began to amble by her at a slow and beautiful pace. She planted a tree in Dan’s honor, although it looked slightly out of proportion with the size of the plaque. Ten years after marrying Dan, Natalie eventually remarried, and Susan and Gregg attended the ceremony. With their permission, Natalie gave Dan’s ring to her new husband.

It took me a year to type Susan’s letters. By the time I finished, I had typed them all over the United States, on various forms of transportation, while single and in a relationship, and living in multiple apartments. In this time, I felt like a witness and a voyeur to Susan’s grief; to some degree, I felt as though I had experienced it. As her words passed through my fingertips, I imagined I was the one writing them. When Dan died, I cried, surrounded by strangers on an airplane. I was almost the same age as Dan when I looked up from typing the last letter. My own life stretched before me, and it was daunting. Then the years slipped quietly by.

During the pandemic I visited Susan, standing six feet away in her driveway, at her home on Snake Mountain. She had been spending her time digging in her garden and photographing the wildlife that visited her yard. She showed me some pictures on her digital camera of a bunny living under her porch that she’d come to love. Then she showed me a picture of a barred owl that she’d witnessed eating another bunny on the edge of the woods.

I was struck by this anecdote—I tried to make meaning of it. I asked her how she reconciled the owl’s need to eat with her love of the bunny. I wondered what it said about the looming inevitability of death, the life cycle, the entanglement of death and beauty; I tried to draw a line between those themes and the themes within her letters.

She told me I was making too much of it, trying to over-philosophize. Life is precarious, she told me. She was simply glad to be alive.

Leave a Reply