Middlebury’s seventh president, Cyrus Hamlin, was 69 years old when he was hired by the College to rescue an institution that was on the verge of extinction less than 100 years after its founding. It was a curious match, Hamlin and Middlebury. The Bowdoin graduate was not the trustees’ first choice; George Nye Boardman, Class of 1847, was, but he had turned down the offer. And while Hamlin had led an active life as a theologian, academic visionary, and engineer, by the twilight of his career he might have seemed like a desperate choice for a school that, by some accounts, needed a miracle to keep its doors open.

Prior to his appointment at Middlebury, Hamlin had been fired from his previous two jobs—as the president of a college in Turkey and as a professor at Bangor Seminary in Maine (he was told his theological views were too old-fashioned)—but Middlebury was desperate. The College’s financial situation was dire, a large portion of its faculty had left with the previous president, and its enrollment was plummeting. When Hamlin arrived on campus in the fall of 1880, just 38 students were enrolled at Middlebury, the lowest figure since 1802, the second year of the College’s existence. (By contrast, 227 students attended Williams that year; 612 attended Yale.)

Hamlin set about raising money and put into motion plans to hire new faculty and construct a new library. In short order, he succeeded on those counts, but Middlebury’s existential crisis did not abate; two years into the Hamlin presidency, the College’s enrollment had dipped to 37.

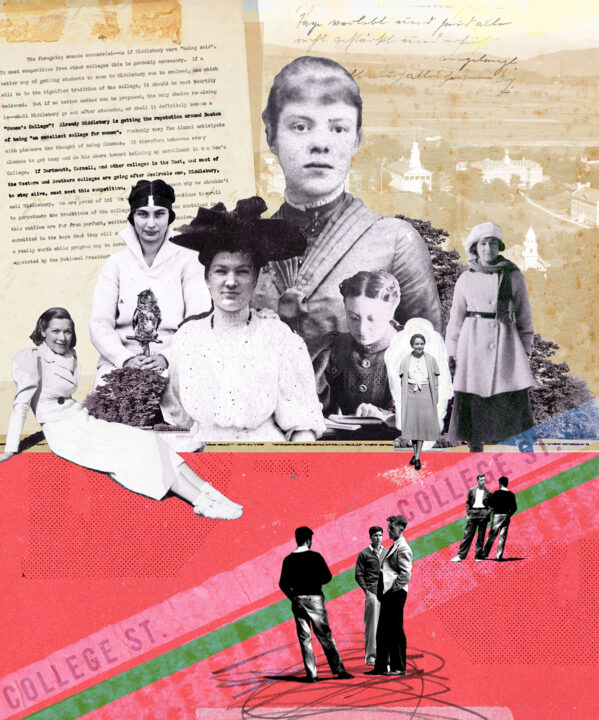

At the same time, there were some folks agitating to attend Middlebury: young women. Middlebury had flirted with coeducation a decade earlier, joining the University of Vermont in exploring the feasibility of opening its doors to women. UVM ultimately did so in 1871; Middlebury did not. But in the spring of 1882, a Cornwall resident and recent graduate of Middlebury High School named May Anna Bolton stepped forward and asked to be considered for admission. Bolton had the backing of Middlebury’s alumni association, and the trustees took up the matter at their June board meeting.

They said no.

But a year later, the issue was back before the trustees. (You could say Bolton persisted.) The College’s enrollment of male students had remained at 37, and at their July 1883 board meeting the trustees debated into the night. Ultimately, they passed a resolution that stated, in part, “that young ladies who desire it may be admitted to the instructions of the Professors and Class rooms at Middlebury College under such regulations as the Faculty and Prudential Committee shall prescribe.”

Now here is where things get interesting. Recall that Cyrus Hamlin was of a rather advanced age. He was now 73 and, by several accounts, hard of hearing. (In her 1953 history of coeducation at the College, Women at Middlebury, Mary O. Pollard, Class of 1896, writes of Hamlin: “He was an old man. Slightly deaf.”) This is significant because the general interpretation of the board’s resolution was that admitting women to Middlebury was an experiment, one that would be continually examined and without the imprimatur of a permanent policy change regarding the admittance of men and women on an equal basis.

Hamlin, though, literally heard things differently, and when he printed the 1883–84 College catalog he included this: “By the recent action of the Trustees, the College offers the same privileges to young ladies as to young gentlemen.”

By the time the trustees saw the printed record, Middlebury had admitted three degree-seeking women for matriculation in the fall of 1883: May Anna Bolton, Louise Edgerton, and May Belle Chellis.

Middlebury had become a coeducational institution, almost by accident. As for the unintended consequences of Cyrus Hamlin’s hearing, perhaps the circumstances simply would have been a footnote to history—were it not for the way Middlebury wrestled with the idea of educating men and women for the next half century.

Middlebury’s board of trustees were fairly upset at Cyrus Hamlin’s proclamation that the College would provide the same privileges to men and women and intentionally muddied the waters the next year by amending Hamlin’s catalog language to read that Middlebury would extend “to young ladies the privileges of the institution.” The amendment was just vague enough to allow the College to hedge on whether women students at Middlebury would be considered the equal of men (and whether that policy would become permanent).

The experiment, if you could call it that, lasted two years and pretty much ended when May Belle Chellis became the first woman to earn a diploma in 1886. She finished at the top of the class, won a prize for academic excellence, and delivered a Commencement address alongside her male peers.

As David Stameshkin writes in The Town’s College: Middlebury College, 1800–1915, “Indeed the ‘sterling character, good sense,’ and academic achievement of the early woman students was a major reason for the board’s decision to maintain coeducation.”

While for the remainder of the 19th century, the women of Middlebury may have been on a near-even academic playing field as the men, their lives certainly were not the same. While many of the men lived in dorms on campus, the women lacked any housing accommodations, and those who were not local were left to rent rooms in boarding houses in town. (Chellis, a New Hampshire resident, lived with Bolton and her family in Cornwall.) The inconvenience was striking. While men could retire to their dorm rooms between classes, the women were faced with longer treks to and from campus. (The College tried to ease the dislocation by creating a study area in Old Chapel for female students. The accommodations were sparse but apparently appreciated.)

Ezra Brainerd, who succeeded Hamlin as president in 1886, noted in his president’s report in 1891 that “there is growing demand for the college education of women. . . . Middlebury College ought to be equipped to meet this demand in a better manner than at present.” He added that the College should own its own building “in which the young ladies who come from out of town can room and board.” The College owned just such a house on the corner of Weybridge and College Streets (now Kitchel House)—not on campus, but very close—and that year the trustees approved a request to convert it into a rooming house/dormitory for women.

And while it might have seemed at the time that men and women were inching closer together, within a decade they would be cleaved further apart.

On a June morning in 1902, the Middlebury Board of Trustees convened for its annual summer meeting at the National Bank of Middlebury. The hot topic on their agenda: coeducation. The previous year, Middlebury had admitted more female students than male (19 to 16) for the first time in its history, and there were rumblings of discontent on campus and off—among the trustees. As Stameshkin writes, “It was then commonly believed that if more women than men were enrolled in a coeducational school, it would not attract male students and would soon become strictly a women’s college.” The trustees fretted that Middlebury was losing competitive ground to all-male schools such as Williams, Amherst, and Dartmouth, and after a lengthy discussion, the board adopted a resolution drafted by trustee James Gifford:

“Resolved that in the judgment of the Trustees, steps should be taken . . . to organize a girls’ college as an annex to our Middlebury College, in which the same general grades of study be taught and the same degrees awarded as to the boys.”

The next year, the board voted to “establish as an adjunct branch of said College a coordinate institution as the Women’s College at Middlebury.” That fall, the cover of the Middlebury catalog contained two names: Middlebury College and the Women’s College at Middlebury. But that was about the only significant change that occurred, at least until the arrival of President John Thomas.

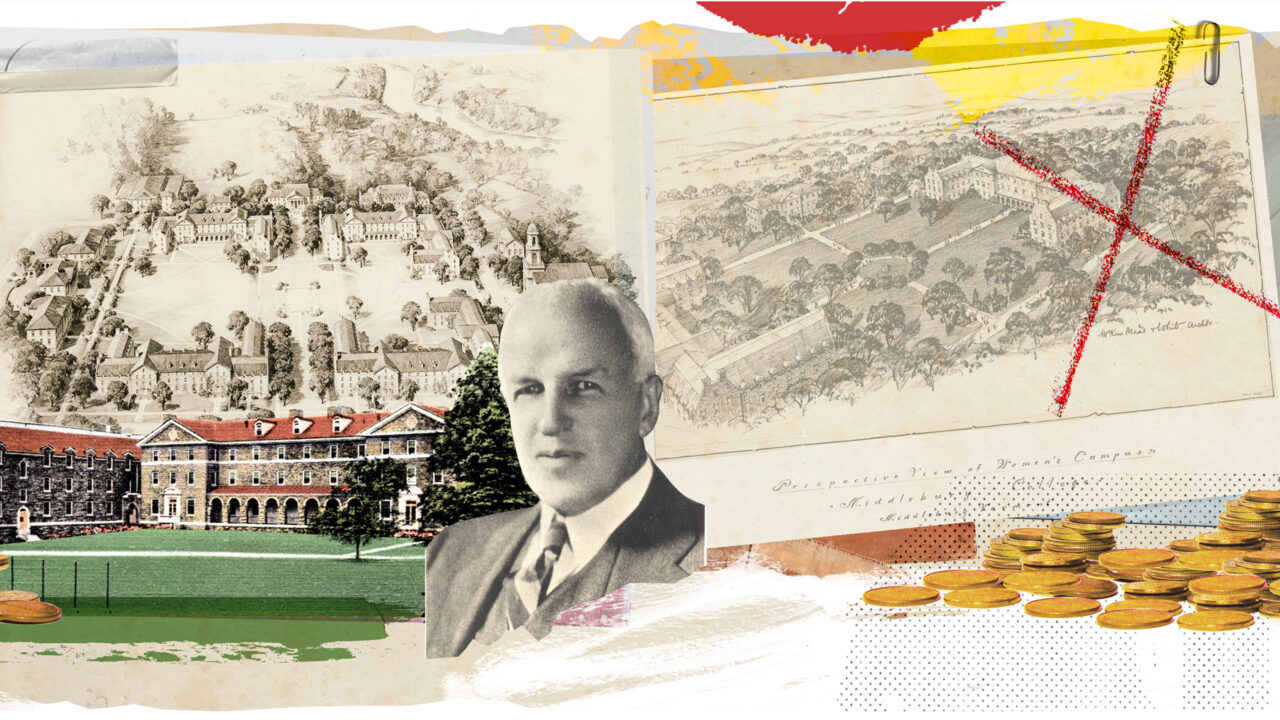

When John Thomas was elected Middlebury’s 10th president in the fall of 1907, he presented as the polar opposite of his predecessor twice removed, Cyrus Hamlin. Thomas was just 37 years old, full of youthful energy and ideas (if not experience), and while Hamlin had been hired to save the College, Thomas was appointed to elevate it among New England’s best. And he did.

During his tenure, Middlebury’s endowment doubled, the campus grew from five buildings on 30 acres to 13 on 144, the faculty tripled in size, and enrollment grew at a steady rate.

Part of Thomas’s vision included the further establishment and growth of the Women’s College, and that meant building a women’s campus. (Stameshkin notes that Thomas believed he had inherited a “feeble” institution and was a strong proponent of the coordinate system of education.) Not long after taking office, Thomas got together with Joseph Battell, Class of 1860, an already-generous supporter of his alma mater who would become one of the most influential benefactors in the school’s history. Battell owned 12 acres of land on the north side of College Street, directly across the road from Middlebury’s main campus.

As Glenn Andres, Professor Emeritus of History of Art and Architecture, tells the story, Battell and Thomas walked the land, where the Johnson Memorial Building and Wright Theatre stand today, and as Thomas spoke of his vision for a women’s campus and his desire to site it at just that place, Battell offered right on the spot to donate the 12 acres. Not missing a beat, Thomas then pointed westward toward a hill that looked down on where they stood. “Imagine us building up there, too,” Thomas said. “We’d have views of the Adirondacks and the Greens.”

That Battell didn’t own the land was no obstacle. He purchased the property, known as the Twitchell Farm, and donated those 23 acres (and the buildings that sat upon the land) to the College as well.

Concurrently, Thomas was in talks with a Chicago philanthropist named D. K. Pearsons, who had donated several million dollars to other colleges and had a professed interest in the education of women. Thomas wrote to Pearsons in the spring of 1908 asking for $50,000 to help establish the Women’s College at Middlebury. The philanthropist responded that $50,000 wasn’t enough to build what Thomas had conceived, and he wanted to know where else he would get the money.

Thomas wrote back to Pearsons, explaining that he expected to raise at least $250,000, but he pleaded with the philanthropist for the $50,000 to start the fund: “For the sum named, we will erect a building that will do lasting honor, and will be a blessing to hundreds of girls who otherwise would be without opportunity of higher education. Such a gift would make you the virtual founder of our work for women, as hitherto we have had no gifts especially for a Women’s College.”

Pearsons responded with the offer of a $1-to-$3 match; if Thomas could raise $75,000, Pearsons would donate $25,000. Thomas convinced a skeptical board to endorse the plan (Stameshkin writes that several trustees laughed at the prospect), and, on the day of his inauguration in late June 1908, he announced the Pearsons challenge to thunderous applause. He received more than $20,000 that day alone, and in less than a year, he had hit the $75,000 goal. (A gift of $30,000 from A. Barton Hepburn, Class of 1871, helped put the fund over the top, and Hepburn would prove to be a pivotal figure in the history of the Women’s College in the years to come.)

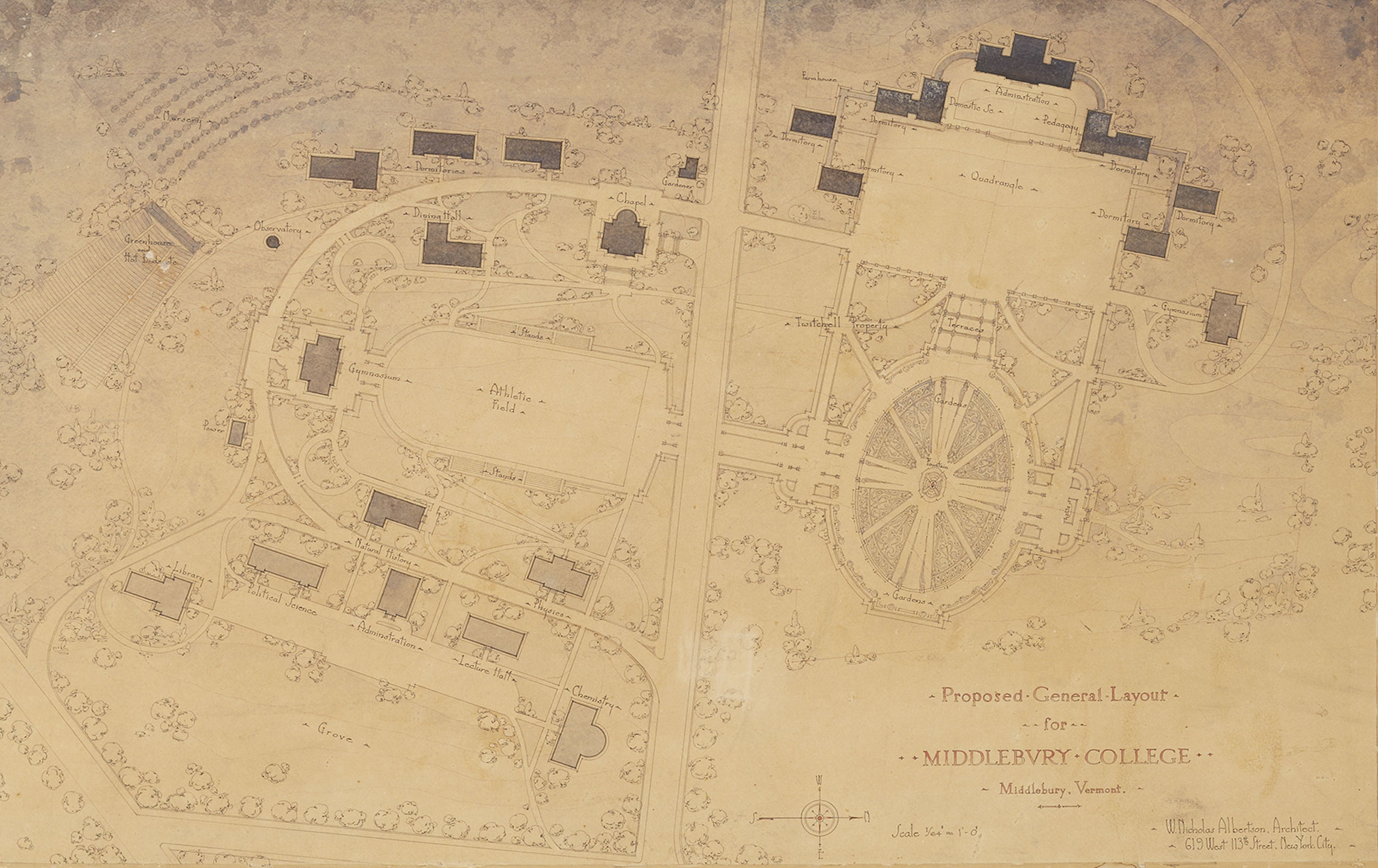

With funding in hand to construct a new dorm and plans to convert the former Twitchell farmhouse (today’s Adirondack House) into a dining hall, Thomas’s vision for a women’s campus began to take shape. He subsequently commissioned a master campus plan from the noted architect Nicholas Albertson, a plan that would not only create a new campus for women but would remake the men’s campus as well.

Not too long ago, Glenn Andres visited me in my office, and he brought with him copies of various architectural plans and drawings relating to the College. We sat at a table, he placed the plans facedown so as not to reveal anything until he was ready, and we began talking about the Albertson plan.

It was a bold move, Andres said, but one of necessity. Those rumblings of Middlebury remaining a weakened institution had not abated. (In fact, the Carnegie Foundation’s General Education Board, a primary source of funding, had been threatening to “reject Middlebury’s applications for funds because it appeared to be in danger of becoming a women’s college.”) So Thomas not only needed to further the coordinated system of education—and there was no better way to do that than establishing an entire campus for women—but he needed to strengthen the men’s side. “And,” Andres said, “the Albertson plan did just that.”

Andres turned the plan over, though covering the right side, the women’s side, with his hand. Looking first at the men’s campus, we saw that the emphasis was on building a gymnasium on the south end of the quad that sits west of Old Stone Row, with a vast football field to its north. Then a proposed chapel on the hill to the west of the field and a cluster of new dormitories both west of the quad, near the chapel, and east near Old Stone Row.

Then Andres removed his hand from the right side of the page, revealing that the two campuses were connected by a road crossing the east-west axis of College Street. On the women’s side, directly across College Street and symmetrically linked with the football field, was an elaborate, elliptical garden. To the west, on the ridge (that Thomas had convinced Battell to buy from the Twitchell family) sat a series of dormitories, with Pearsons Hall in the middle, as the anchor.

From this plan, only three buildings were constructed: McCullough Gymnasium and what would be Voter Hall on the men’s side and Pearsons on the women’s. When asked why this was as far as the Albertson plan had progressed, Andres replied with one word: “Money.”

During the next several years, Middlebury made incremental progress on establishing a more robust campus for women on the north side of College Street. In 1912, it purchased a few more acres contiguous to the former Twitchell Farm property. In 1913, the Board of Trustees established a women’s advisory board, which would advocate for the Women’s College as a conduit between it, the Middlebury administration, and the trustees. In 1916, Eleanor Ross was hired as dean of women, the third dean in a handful of years; after the prior two deans didn’t work out, Ross proved to be a pillar of stability, serving in the position for more than three decades.

Yet, the trustees grew restless. In their view, Thomas was not moving quickly (or strongly) enough to establish a clearer distinction between the men’s and women’s colleges. So Thomas appointed a trustee committee to study the matter, naming Hepburn, now on the board, as chair of the committee. Hepburn’s report, submitted to the board in December 1919, laid out a handful of options:

- Close the College to women immediately after those already in school

had graduated. A “radical step,” yet one that would “relieve all conges-

tion as to housing, recitations and otherwise.” - Incorporate a college for women with a separate Board of Trustees,

separate commencements, separate classes when practicable, and

distinctly different names. - Or, “Go on just as we are at present, as a Co-educational institution.”

At the trustee meeting a month later, the board adopted a measure that seemed to be a hybrid of the second and third recommendations, stating that “the most feasible plan to preserve the tradition of the College . . . and to meet the growing demand for further separation of men and women at the College . . . would be to develop a semi-detached institution for women, which may or may not bear the same name of Middlebury.”

Though he didn’t say anything publicly, Barton Hepburn was not happy with the outcome. As the man most capable of funding the buildout of a women’s campus—the president of Chase National Bank, Hepburn was one of the country’s leading financiers and worth millions—he never donated money for construction on the women’s side of College Street, despite Thomas’s best fundraising efforts. Hepburn felt that the Middlebury president had not gone far enough to better segregate the two colleges.

That might have changed when Paul Moody replaced Thomas as the president of the College in 1921. Moody used his inaugural address to argue forcefully for segregated institutions, and he often spoke of coeducation with disdain (he suggested that since Middlebury first admitted women in 1883, it had “stood still” while colleges such as Williams and Dartmouth had progressed).

Moody and Hepburn may very well have been the perfect ideological match, and Middlebury’s president may have found the ideal donor to pursue his—and the College’s—renewed vision for a completely separate Women’s College and campus. But he never really got a chance to find out. In January 1922, just a few months into Moody’s tenure, Hepburn was hit by a bus and killed on Fifth Avenue in New York.

Suppositions about his dissatisfaction with Middlebury had been well founded. While Hepburn’s will had initially stated that the residue of his estate should be left to Middlebury for the “purpose of establishing a Women’s College,” a subsequent codicil had revoked this bequest. Instead, the multimillionaire bequeathed $200,000 to his alma mater.

Despite the loss of an ally in Hepburn, Moody kept beating the drum of more completely segregating the sexes. In a letter to trustee James Gifford not long after Hepburn’s death, Moody excitedly shared an idea he had heard from a friend: that the following year’s first-year class of women should be placed at Bread Loaf. In addition to alleviating a housing crunch, such a move would “indicate clearly to the public that we are dead in earnest about segregation,” Middlebury’s president wrote.

Now, James Gifford was no shrinking violet when it came to promoting separate institutions, but he found this idea to be ludicrous. Responding to Moody, he wrote that he was a “doubting Thomas” on the matter and his mind was unlikely to be changed. He wrote:

“First, to put 100 girls in the midst of the forest of the Green Mountains six miles away from the railroad would be like sending them to Dannemora, which by the way, you may know, is one of our New York prisons on the edge of the Adirondacks.

“[And] I assume that all the buildings at Bread Loaf are built for summer and not for the frigid cold of a New England winter?”

It doesn’t appear that the idea was brought up again, but the next decade—the 1930s—saw a renewed push for a distinct Women’s College campus on the north side of College Street.

At the June 1930 board meeting, the trustees again took up the issue of coeducation—or affiliated education—in earnest. James Gifford read from the trustee minutes from the June 1903 board meeting when the Women’s College was established, and the board went on record as saying that “a continuation of coeducation as practiced at Middlebury at present is undesirable.”

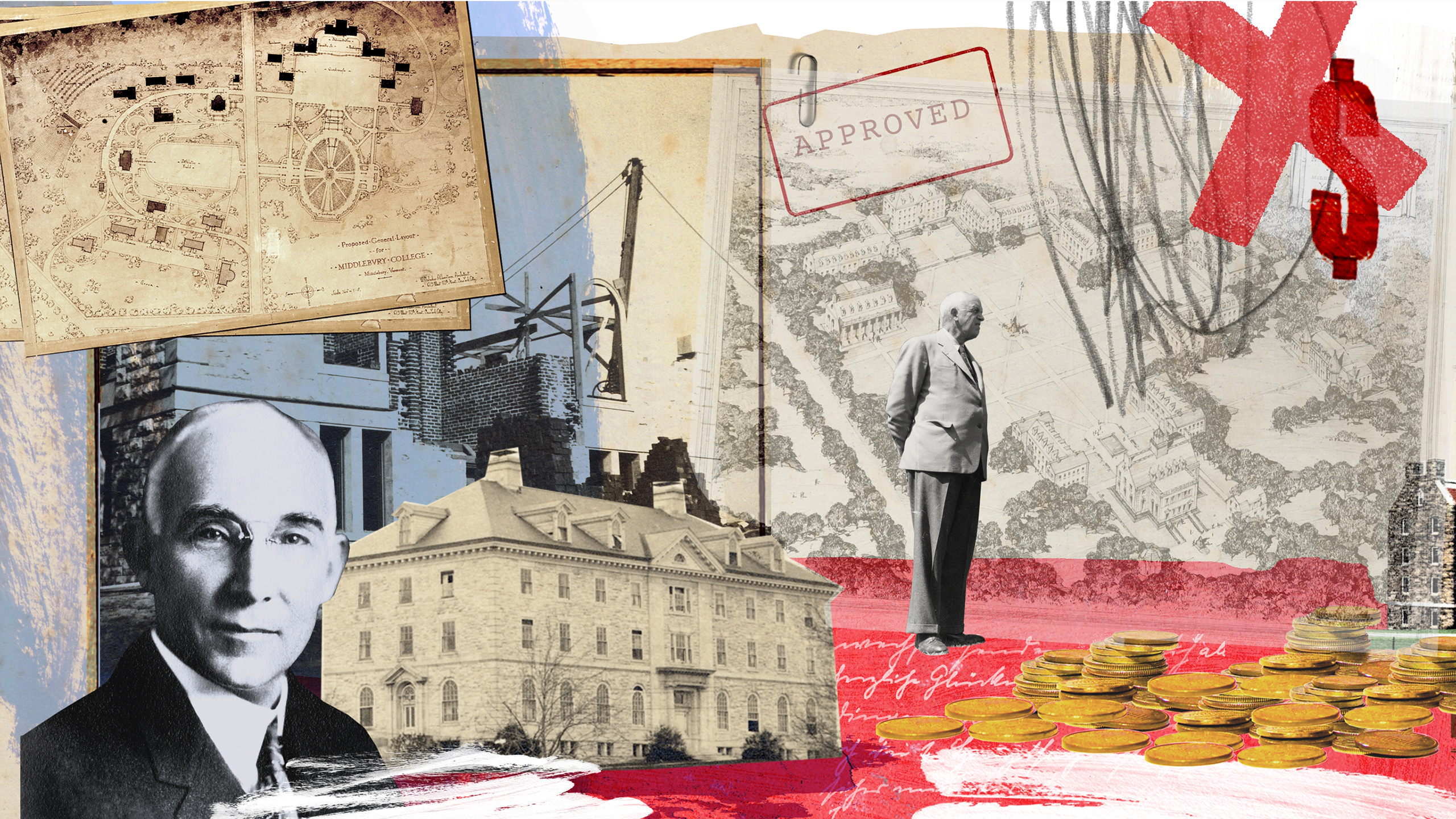

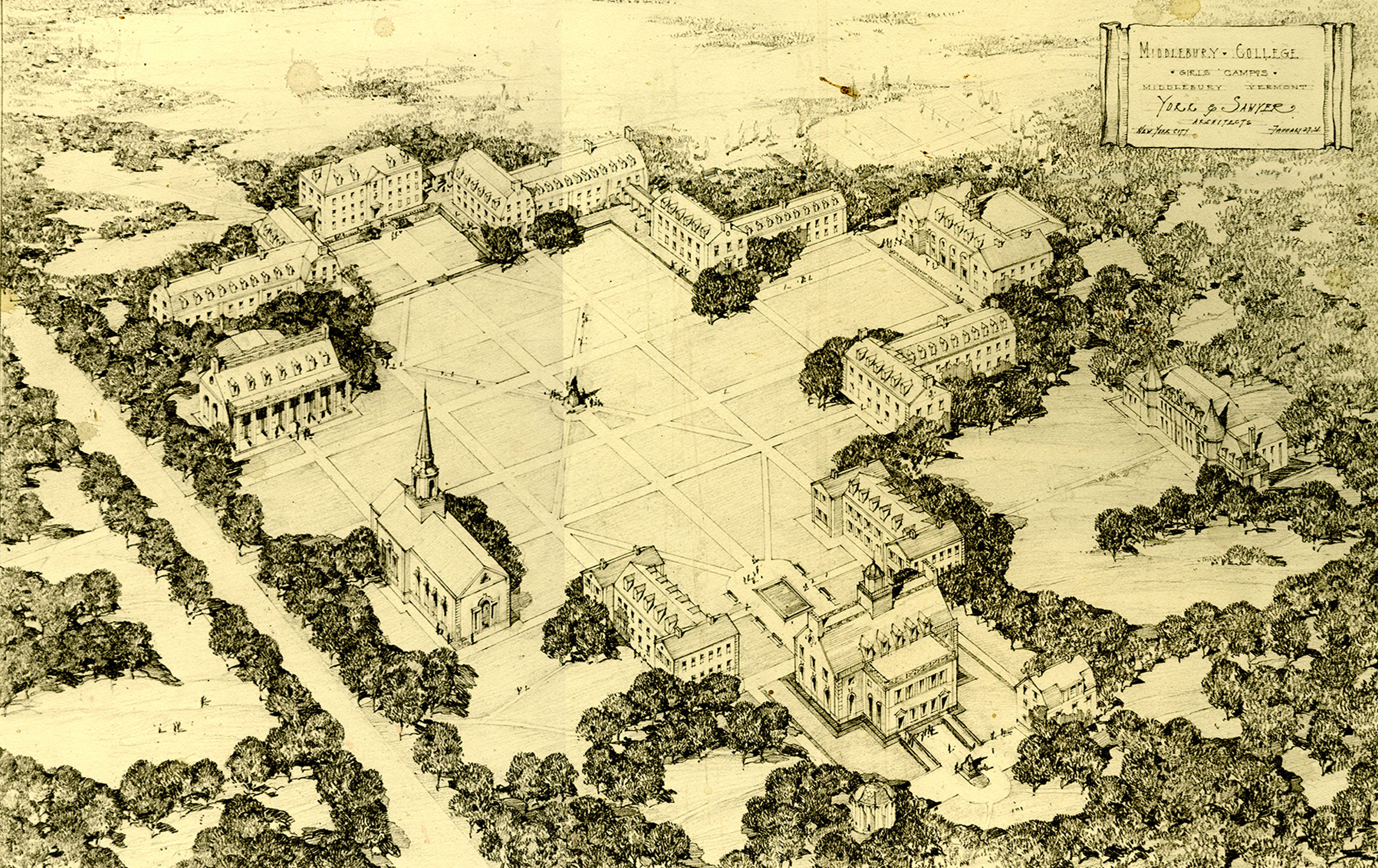

Following the meeting, President Moody moved quickly, commissioning another master plan for a women’s campus, this one designed by the architects York and Sawyer, who had just completed an expansion of Starr Library.

The architects submitted their plan in 1931, and it was an ambitious statement in style and scope. Consisting of 10 new buildings—including a chapel, a library, classrooms, and a gym—all designed in the colonial style, the York and Sawyer campus would be a self-contained entity.

Where the Albertson plan had intentionally aligned with the men’s campus, the York and Sawyer version purposefully did not.

Back in my office, with the York and Sawyer design spread before us, Glenn Andres pointed out that the main entrance to the women’s campus did not align with anything on the men’s campus. “With that, with the style—everything was going to be in red brick—the architects and Moody are really making a statement here.”

But the plan never caught on. It’s been suggested that a colonial style was a step too far. And then there’s the timing. In 1931, the country was just two years removed from the stock market crash. But that didn’t seem to inhibit Moody; two years after the York and Sawyer plan came and went, he commissioned another master plan, this one conceived by an architect named Dwight James Baum. This plan was more conventional—stone buildings, a central quad—but still ambitious, with a chapel facing Pearsons across the quad and a library on the north end, on a straight-line axis with Starr Library across the road and to the south.

Despite a price tag of $3 million to $3.5 million, the board approved the plan at its June 1935 board meeting (this in spite of the fact of, you know, the Great Depression), and placed an emphasis on construction of one or two dorms that would face College Street at the east end of the quad.

Since first seeing the Baum plan in 1933—and facing another housing crunch—the trustees committed to building one of the dorms that lined the east-west road into town. But Moody’s plan to raise $2 million couldn’t get off the ground (again, the Great Depression), and the board scraped to find a way to pay for the new dorm, which had an estimated price tag of $160,000. (From a 1933 report from the Women’s College Committee: “Can the finance committee find out how we can get a hold of $160,000?”)

Two years later, the estimated price tag on one dorm had more than doubled to $392,000, but the College had found a lifeline in the ghostly figure of Joseph Battell. The story is well told at Middlebury, but it’s worth a recap: In 1915, Battell bequeathed his 30,000-acre mountain estate in Ripton to the College. And in 1933, strapped for cash, Middlebury sold 22,000 of those acres to the National Forest Service. The receipts for the sale? A little less than $400,000. It was almost a dollar-for-dollar match for the cost of the new dorm, which was completed by the fall of 1936 and named Forest Hall.

The story basically ends here. Forest Hall was the only building constructed from the Baum plan. Every year or so, the board would express the desire to establish a distinctive name for the Women’s College, but at each meeting, they kept deferring the action to the next; the “big” change in 1937 was a word swap: the Women’s College at Middlebury became the Women’s College of Middlebury.

And then came the 1940s and another World War and a very different campus. (In 1941, Middlebury couldn’t fill the dorms on the men’s campus, so in an “emergency motion” the College decided to close two smaller cottages that housed women and move the students across the road, where they would live . . . in Hepburn Hall. The irony is rich.)

And then, the coordinated education of men and women ended not with a bang, but a whisper. The Advisory Committee to the Women’s College was discontinued, and for the first time, women were named to the Board of Trustees. The board’s standing Committee on the Women’s College became the Committee on Women’s Activities in 1949. And in 1950, the institution’s catalog contained just one name: Middlebury College.

Leave a Reply