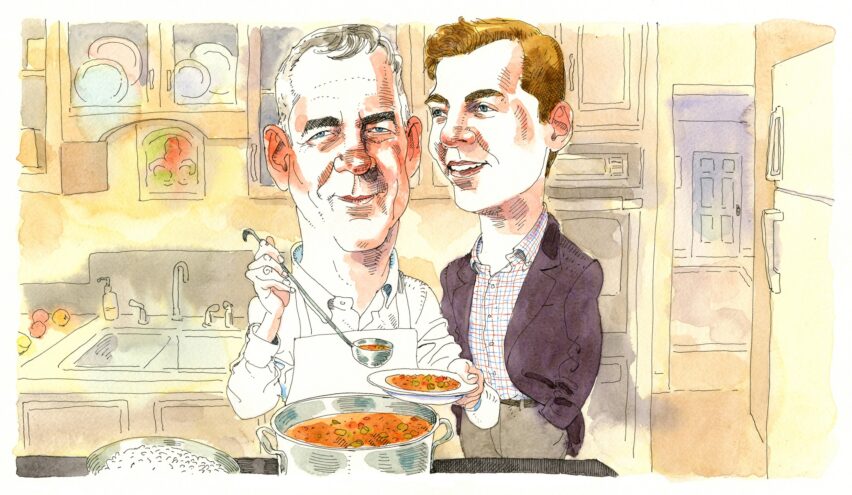

“Just a little buttah . . . ” Dad’s mellow Southern accent melts his pronunciation. He hunches over the stainless steel pot, grinning as he stirs in a quarter stick of butter. “You don’t need the butter.” Mom always gives him a hard time about the healthiness of the Cajun food he cooks. “I put hardly any in!” Dad’s response is as convincing as a kid who, unaware of the smear of chocolate in the left crease of his lips, swears he didn’t sneak a cookie from the jar.

“I put haahdly any in!”

Dad’s response is as convincing as a kid who, unaware of the smear of chocolate in the crease of his lips, swears he didn’t sneak a cookie from the jar.

“He’s a lost cause,” Mom sighs, half critical but mostly loving, as she heads downstairs to work out. She tries to hide her endearing amusement so as to not undermine her ongoing effort to get Dad to adopt a healthier lifestyle.

Dad grew up in Louisiana but moved to New York City in his 20s. My friends consider him extremely Southern, citing his accent as evidence. “You should meet the rest of his family,” I laugh. Their lifestyles—Bible-toting churchgoers who hunt, raise livestock, and serve up overflowing platters of rich comfort food at huge family gatherings—are mostly childhood memories to him.

Despite her health-related concerns, Mom occasionally lets Dad cook his favorite Southern meals. Shrimp Creole, jambalaya, and gumbo are the classics, but when Mom’s not home, it’s a free-for-all. “Dad doesn’t eat any vegetables when I’m gone, even if I stock the fridge with them,” she complains. I shift my gaze to conceal my growing smile as I recall a weekend filled with homemade fritters and fried chicken, the perfect nourishment after a late-fall afternoon of golf. Mom never fails to notice the spattered oil left on the stovetop after our subpar cleanup job, but I like to think of our endeavors as secret.

Last year, in place of traditional family Christmas presents, I suggested we give one another a task to do that we valued and thought could better the recipient. I asked my parents to meditate for 40 days; Mom asked me to floss my teeth; Dad gave me a card. His familiar scribble haphazardly covered the left side, occasionally crossing the crease, encroaching on the generic Christmas message printed on the right. “As a gift this year, I’ll teach you my version of Louisiana gumbo. No meat! No sea creatures! Roasted veggies and a rich veggie broth.”

I had recently gone vegan, a choice constantly contested by friends and family.

“How are you going to get enough protein?”

Mom loves that one. My response cycles between defensively citing pro-vegan research, a sigh of resignation, and frustration.

Any Louisianan will tell you sausage is the most important ingredient in gumbo. It enriches the broth and accounts for the defining heartiness of the soup. To a Cajun food connoisseur, vegan gumbo is an absurd paradox—the exclusion of meat jeopardizes the integrity of the dish.

Prior to cooking, we always golf. Each of us carries one club and ball. Last Christmas, walking the course, Dad asked me about school, postgrad plans, and relationships, and shared with me his experiences with these timeless uncertainties. I asked him about his business and aspirations for retirement. The conversation continued into the kitchen as we chopped an assortment of vegetables, the steam produced by the roux thawing our hands.

Later, I scraped the final grains of gumbo-infused rice from my bowl and smiled at our success. Between spoonfuls, Dad suggested future fine-tunings to our creation. As the soup warmed my still-chilled body, the time spent with my dad warmed my soul.

Leave a Reply