My mom FaceTimed me on Saturday, September 11, joking that I should call up my dad and brother and remind them that I’m the only reason either of them are alive right now. We laughed about it, but it felt heavy.

I know—more than most—what it would have been like to lose someone on 9/11. At the time of the attacks, my dad was working in an office on the 70th floor of the World Trade Center. The story goes that he and my mom had stayed up the night before attending a birthing class. Because of this, my dad slept through his alarm and left twenty minutes late for work. Sometimes, running late is lucky. Sometimes, it saves your life.

He took his normal subway route, but when he got out at his stop, all hell had broken loose. Both buildings had collapsed. Some of his colleagues were able to make it out, and he walked across the Brooklyn Bridge with them. Others didn’t escape in time. Smoke and dust filled the air, and made its way over to 5th Avenue, where my mom was working. She heard about the attacks through a combination of radio and television. Her friends did their best to keep her calm. Cell service had been lost and she had no way of contacting my dad. So she, like so many others across the city and around the world, was left bracing herself for the worst.

My parents eventually made their way home and dealt with the aftermath of the attack together: as New Yorkers whose city was in turmoil, as friends of victims or their loved ones, as Muslim Americans whose moral compasses were being called into question solely on the basis of their religious identity, and as expectant parents who would have to learn how to raise their child in the midst of all of this.

Two years later, my mom gave birth to my brother. And neither of us had to grow up with a shadow of loss hanging over us in place of my father. So, last Saturday, I woke up feeling lucky. A difference of twenty minutes changed the entire trajectory of my life. Sometimes that feels too big to really comprehend.

But it didn’t take long for the dread to settle in, as it usually does. 9/11 shaped my life, and continues to do so, in ways that are often much more intangible than the loss of my father would’ve been.

I’m not always able to recognize how drastically security tightened in reaction to 9/11 because that’s all I’ve ever known. When traveling together, my mom tells us what airports used to be like “in the before time,” and my brother and I react with the same disbelief that we usually reserved for fairy tales as kids. Walking your loved one right up to the gate without having to go through security or take your shoes off, crying while you watch their plane depart—it’s the stuff of movies now, but it was her reality. My reality consists of sitting on cold airport floors, waiting for hours while my mom (or dad, depending on who I’m traveling with) gets questioned by the TSA for being too brown or having a name that sounds too Arab. Freedom of movement is a foreign concept to me, a privilege that I have never been afforded.

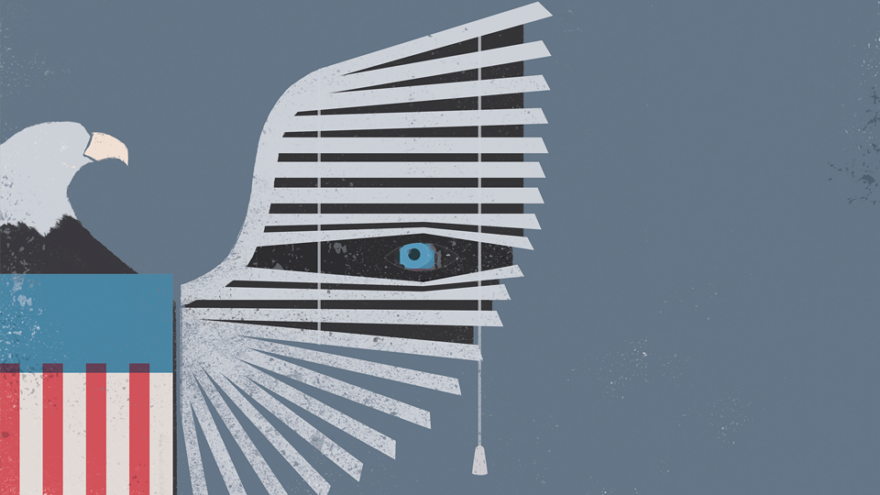

There was a presumed sense of safety that dissipated for everyone in the aftermath of 9/11, but especially for Muslims. The Patriot Act isn’t some vague piece of legislation, but something that has had very real consequences for my community. I live near a section of Astoria, N.Y., called Little Egypt (on Steinway Street), which is home to a large population of Arab and Muslim immigrants. Steinway was one of the areas that came under police scrutiny. When reading through reporting on their tactics, I saw so many familiar places— our local halal meat store, one of our mosques, some of my favorite restaurants. While much of the surveillance is covert, its presence is still felt. It creates a sense of unease. It’s the same unease that follows me around when I am walking to the mosque, in airports and on planes, and in predominantly white spaces. The sense that I am a suspect. Guilty until proven innocent. Terrorist until proven otherwise.

I spent a good portion of my childhood in the library, searching for books where I saw myself reflected as anything else. Through newspapers and TV shows, I learned to see myself through the eyes of people who feared me and what they thought I represented.

Islamophobia is often discussed in the context of “post-9/11,” as if hatred against Muslims sprang into existence the moment the towers collapsed. But my mom dealt with it when she was growing up in Philly—just a different brand of it, rooted in Orientalism, as opposed to the War on Terror. Regardless, the rhetoric against Muslims has always been predominantly negative, especially on and around 9/11.

I feel frustrated when I open social media and am bombarded by posts that are, at worst, borderline white supremacist and, at best, solely ignorant. They’re usually America-centric, often failing to account for the violence enacted in response to 9/11, both at home and abroad. Violence enacted in the name of vengeance, disguised as protection from a war that America created.

This discourse has started to shift, especially with the recent withdrawal of American troops from Afghanistan. But even when we do acknowledge the massive loss of human life that occurred in response to 9/11, it’s still reductionist. It’s a number instead of people with faces, with names, favorite colors, food preferences, and a baby on the way. It’s a perpetuation of “other”ing, even if the intention is to foster empathy. Just as I would have wanted my father to be honored in the fullness of his humanity, I want that for every other victim.

I’m turning 20 next month, just weeks after the 20th anniversary of 9/11. And if I’ve learned anything in the past 20 years, it’s how to make space for nuance. How to balance dominant oppressive narratives with my own lived experiences. How to navigate my so-called dual identity—my Muslimness and my Americanness, which have always coexisted for me, but seem oxymoronic to others. How to both mourn the lives lost on 9/11, and all the lives lost in its wake. How to honor other people’s grief, while making space for my own.

This essay originally appeared in the Middlebury Campus, where Daleelah Saleh is a member of the Opinion Desk.

Leave a Reply