Reproductive justice is serious. Miniature golf is fun. Leave it to Carly Thomsen, assistant professor of gender, sexuality, and feminist studies and creator of the Games Project, a pedagogical tool, to put the two together. The result, made possible through a wide-ranging collaboration between students, educators, colleges, and organizations, is what Thomsen believes to be the first-ever Reproductive Justice Mini Golf Course. On Friday, May 12, it opened to enthusiastic crowds on the rink floor of the currently ice-free Chip Kenyon ’85 Arena.

I interrupted a very busy Thomsen the morning before the opening, while students and helpers buzzed around us painting plywood, setting up holes, cleaning, making phone calls, or briefly popping in to ask Thomsen last-minute questions. Though she clearly had other things to do, and confessed to a lack of sleep, she took me on a tour of some of the 11 holes—designed like individual stage sets—that would soon be open for play.

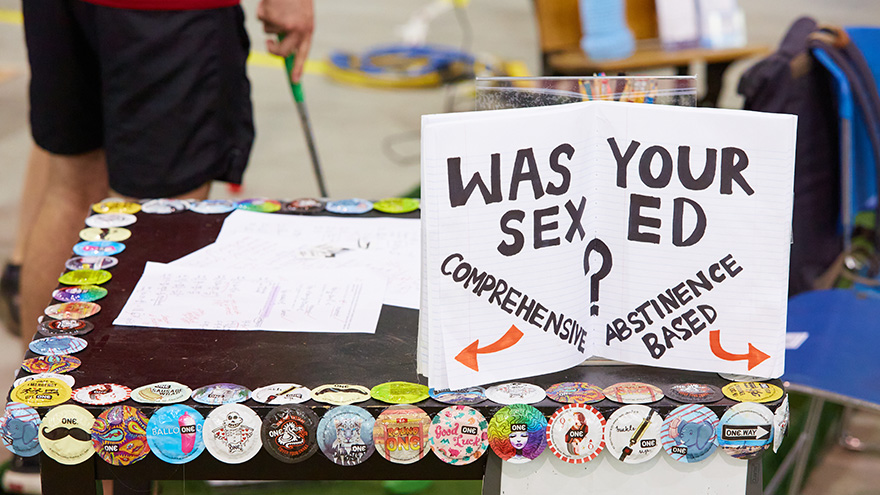

Each hole represented a different aspect of reproductive justice, from sex education and incarceration to legislation, adoption, abortion access, and more. At a glance, the course looked like a typical, quirky miniature golf course, each hole built like its own stage set. A deeper look, however, revealed designs, artwork, and multimedia installations reflective of a much deeper theme.

Some holes merged content and gameplay. On a hole dedicated to foster care, for instance, the player’s ball falls through a Plinko-like set of pegs. The ball’s outcome, like a child’s foster care experience, relies largely on chance.

Other holes moved beyond thought-provoking to heart-wrenching, such as the hole that examines the effect of incarceration on families, where players putt through an enclosed 6-by-9-foot space—the size of an actual solitary confinement cell. They can pick up a telephone handset outside the cell to hear preserved recordings of conversations between a current Middlebury student, who was 10 years old at the time, and her then incarcerated mother.

Next to the course, Rayn Bumstead ’21 raced to finish painting a row of bright green, cartoonish plywood dinosaurs, which would soon be placed at the beginning of each hole. (Bumstead designed the dinosaurs, as well as the course fliers and website.) Variously clad in bouffant wigs, lingerie, fishnet stockings, and vintage bathing suits, the dinos—which Bumstead described as “unruly, feminist, monster-type things”—added a kitschy touch reminiscent of roadside mini golf courses. Each would soon sport an informational placard and QR code that players could scan for more information about the topic of the hole they were on.

“The placard text on the dinos is meant to just pique people’s interests,” Thomsen said, “and then they can start learning more while they’re here.” She explained that the playfulness of the dinosaurs was to help offset the gravity of the issues raised at each hole. “In all the QR codes, there’s not a single hole that doesn’t talk about racism and classism and metronormativity and basically the impacts that our social location has on our lives.”

A BROAD COLLABORATION

After the tour, Thomsen invited me into a cramped, Plexiglas-walled space off the rink—the announcer’s box in the colder months—that was serving as her temporary office. There she explained to me that for the past seven years she has incorporated project-based learning into her teaching. The Games Project challenges students to demonstrate their understanding of the studies by creating educational, playable games for their classmates. The mini golf course grew out of her desire to build on that model, but “to improve, or scale up, or try it in a new way.” She landed on the idea of miniature golf as a way to turn a single game into a group project that could extend the learning—and the fun—to the whole community.

After securing modest grant funding from a variety of sources, Thomsen and her collaborators began pulling the project together. Students in the studio art class Feminist Building, which Thomsen cotaught with studio art technician Colin Boyd, built most of the holes. Students in her Politics of Reproduction class created the text of the QR codes and the placards. Students in David Miranda Hardy’s introductory film class made short films to be played around the course. Students and faculty at other colleges—including the University of Kansas, Providence College, Metropolitan State University of Denver, and Hamilton—and staff at nonprofits such as Vermont Works for Women helped with design and construction.

Student-made art appeared around the golf course. Some was created as part of a Public Feminism Fellowship supported by the Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies last summer. Some was made at a Feminist Earth Day event in spring 2023, through which students created art that represented overlaps in environmental and reproductive justice. The Earth Day event was organized by Thomsen’s research assistants Isa Perez-Martin ’25, Lu Mila ’24, Arthur Martins ’23, and Liza Obel-Omia ’23.

Thomsen says the breadth of the collaboration was both the best and the hardest part of the project for her. “I’m proud of the fact that we managed to do something that is entirely unlike anything that’s been done before. And in the process, I feel like relationships have been deepened, sustained, and created.” On the other hand, she admits, “it’s a lot of moving parts.”

I shared with Thomsen my apprehension that I’d be walking into an aggressively activist space, what might be called “woke,” in its co-opted, pejorative sense. She wasn’t surprised, saying feminist and queer studies as a discipline is often assumed to be synonymous with feminist and LGBT activism. “For the most part,” she said, “you’re not going to find feminist or LGBTQ or trans activist slogans here. . . . In many ways, what you’re finding is that feminist studies is giving us tools with which we can critique dominant ideas about gender that circulate among people who think of themselves as feminists or queer.” She believed players who engaged with the QR codes would “leave with a much more developed understanding of what feminist and queer studies as academic fields can offer our thinking about reproductive justice.”

I also expected the course to focus mostly on abortion rights. It did not. Part of the goal of the course, according to its website, was “to push feminists to see issues other than the legal right to abortion as crucial reproductive concerns. Doing so requires fighting against the sexism, racism, classism, ableism, and homo- and transphobia that make both parenting and accessing abortion more difficult for some than others.”

A term Thomsen used earlier—“social location”—stuck with me. The words highlighted the disparity of reproductive justice depending on one’s place, in both a geographical and socioeconomic sense. Not just abortion access but things like the availability of prenatal care, child care, and a safe environment in which to raise children varies widely, between states, between rural and urban areas, between people of different financial means. Even one’s proximity to places prone to natural disasters—an increasingly common issue related to climate change—can affects one’s access to reproductive justice.

I asked Thomsen if she worried that anyone might be offended by the themes raised by this project. While she acknowledged that there are people who might not agree politically with the message of the mini golf course, she welcomed them. “If they’re here, then they must be open to some degree to conversations that maybe they’re not used to having. Or that’s my hope.” She went on: “What I hope, really, is that [the course] inspires people to think in more complicated ways about what reproductive justice means, what feminist studies’ and queer studies’ approach to reproductive justice gives us, and then ultimately to do something with that information and knowledge.”

THE GRAND OPENING

I returned on Friday afternoon, during the opening, to find the halls of the Peterson Family Athletics Complex bustling with students and families with children, who laughed and talked as they headed for the rink or for the exits, some nibbling popcorn, others clutching scorecards.

I ran into a family of four on their way to get dishes of lu•lu ice cream outside the course. The mom, Rhoni Basden, is the executive director of Vermont Works for Women, whose staff had built a hole designed remotely by a team from MSU Denver.

She said, “I think the idea of raising awareness about a social issue, especially a women’s rights issue, in this way that’s interactive and that you can engage families in is super cool.” She said her kids, who are eight and five, had a great time playing, and although some of the topics were beyond their developmental level of understanding, the course prompted them to ask questions. “It gets them thinking about things differently and it allows them to recognize that these issues are important,” she said.

Outside the crowded rink, I met one of Thomsen’s research assistants, graduating senior Arthur Martins, who had worked on the project in numerous capacities, including writing some of the copy for the QR codes. Martins, who hails from Brazil, admitted he had never played miniature golf before this project. He described the experience of seeing this group effort come to fruition as “just fun” and was happy to see the community come together over difficult issues like reproductive rights and climate change. “It feels very appropriate, instead of feeling so gloomy and doomy about everything that’s going on, to just put a ball down and then hit it with a putter and play some mini golf.”

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

A few days after the opening, I emailed Thomsen for her impressions. “Not only did approximately 400 people attend the opening event,” she wrote back, “but students and staff have been playing nearly every time I have stopped by the rink since the grand opening, and I’m receiving lots of emails and texts asking about open hours.”

Reiterating that there was more behind the golf course than players might know, she praised the many people who had contributed their art, design, building, and research. “The physical mini golf course is just the tip of this much larger iceberg,” she said. And the overwhelming response to the course proved it had succeeded in engaging people on important topics in an entertaining way. Thomsen concluded, “Seeing this excitement and interest makes me hopeful for the future of feminist activism.”

Before leaving the opening that Friday, I had asked Martins how he would define the Reproductive Justice Miniature Golf Course: was it a game, an art installation, or an educational tool? He didn’t have to think long. “It’s what happens when you think of the classroom as the entire world, and you center fun in your learning.”

The Reproductive Justice Miniature Golf Course will remain open in Kenyon Arena through July 15. Hours are Thursday, 4–7 p.m., and Fridays and Saturdays, 2–5 p.m. Learn more at https://www.feministminigolf.org/.

Leave a Reply