In this country, and around the world, ideals of shared civic values that transcend political, religious, or ethnic differences are under threat, arguably more than at any time since the Second World War.

Nationalism and authoritarianism are on the rise, undermining freedom, inclusivity, and equality of opportunity everywhere. Communities have lost the ability to debate, strategize, and organize with one another to solve problems in a constructive way.

So what are we doing about it?

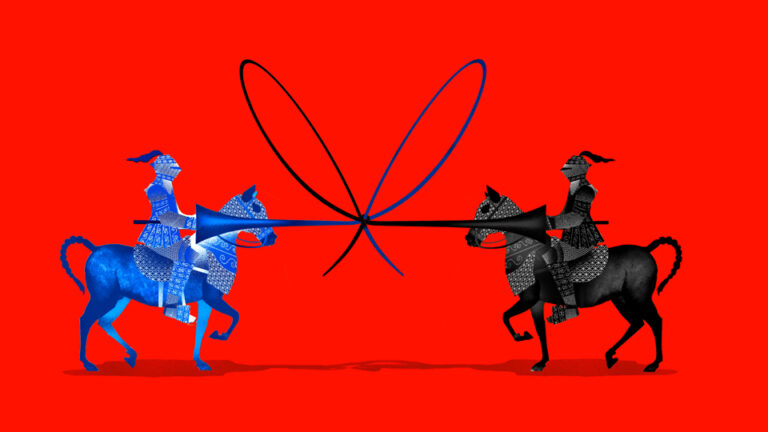

We can’t end all conflict, of course. But can we transform how we deal with it?

Conflict transformation—analyzing the structural issues that contribute to conflict and designing solutions that place inevitable tensions on a positive, rather than negative, trajectory—is a growing practice. And at Middlebury we are making such a practice part of our system of values.

Many of you may know that last spring, Middlebury received a $25 million grant to establish the Kathryn Wasserman Davis Collaborative in Conflict Transformation (CCT).

The collaborative formalized a structure that had been building over the course of a year and a half, as faculty, staff, and students met to think through how we develop Middlebury’s considerable strengths in these areas.

Through the CCT, we have created five areas of focus to infuse conflict management skills in all parts of Middlebury: 1) in the high school curriculum through our Bread Loaf Teacher Network; 2) throughout our undergraduate curriculum, with a faculty focus on classroom conversations and a student focus on restorative practices; 3) among our experiential learning opportunities outside the classroom and through our extensive internship program; 4) in our graduate curriculum through fellowships in conflict transformation; and 5) within our global curriculum as we provide intercultural experiences for students to learn about other approaches to conflict. We are also funding key faculty research in current global political and environmental conflicts, the historical resolution of conflict, and the role of decision making in conflict situations.

In all of this, our goal has been to create “conflict transformation as a liberal art” and make the skills of managing conflict available to all our students, faculty, and staff. Over the seven-year course of the grant, we hope to share our approach with the world of higher education and learn from similar initiatives at other institutions.

I am excited to report on what we have been learning in our first eight months. We have been developing a new curriculum in leadership and literature at the Bread Loaf School of English for BLTN, our deep network of high school teachers across the country. We have trained over 80 undergraduate students in conflict transformation skills, including restorative practices. We have hosted a College-wide symposium, the Clifford Symposium, in the study and practice of conflict transformation skills. We are training 25 new faculty in advancing facilitation of difficult dialogues and launching a Conflict Transformation Skills course for J-term in 2023, with over 70 students enrolled. At the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, we have funded 68 student fellows to study conflict transformation skills and integrate them into their foreign policy and language teaching professional development. Their projects include the study of the impact of the war on nuclear power in Ukraine and scientific collaboration as a form of conflict transformation in totalitarian states. And in our Schools Abroad we are funding transformative student experiences, such as the environmental conflicts in Brazil and the role of women in conflict mediation in Cameroon.

We have also funded major research grants for faculty. Want to learn about food scarcity and conflict in Cyprus and Turkey, or global models of labor arbitration, or North Korea and strategic empathy, or water rights and conflict transformation? Ask a Middlebury faculty member.

There is so much more to share in terms of the specifics of our progress. But the more important thing to share is what we are learning. The most important lesson for us in these early stages is, as executive director of the collaborative Sarah Stroup has put it, the power of experiential learning in teaching conflict. I like to use the phrase the power of making democracy concrete through the active management of conflict. In 2022 and beyond, we learn best about how to navigate a difficult democracy by being active in it.

What do we mean by this? Connecting the skills in conflict management to democratic citizenship is an important link to make. That begins, of course, with participation. We already expect all our students to participate in democratic processes—and indeed they do. Our Middlebury students vote! (Middlebury won in three out of four categories of the NESCAC Votes All-In Campus Democracy Challenge on voting rates. And Washington Monthlyranked us one of the top two colleges in student voting and among the top 15 who promote turning students into citizens by promoting democratic participation.)

But to be a citizen is to be a leader. And so, at Middlebury, it is not enough just to participate in democracy; it is important to find a way to answer the need in our society for people to step up and lead. And in today’s polarized world, that means being unafraid of fractious conversations and contentious public spaces—in other words, being willing to tackle conflict head on.

Take the example of our student Gayathri Mantha ’25, who served as an intern at Addison County Restorative Justice Services this past summer. In her work, she was asked to help adult and youth offenders acknowledge and repair the harm they had caused through their actions. At first, it was challenging for Gayathri to help people who had caused a lot of harm to the community, but through her internship she realized that community support can turn damaging conflicts into situations of constructive engagement.

Or consider the class How Democracies Die, taught this past fall by Sebnem Gumuscu, associate professor of political science and director of the Collaborative’s undergraduate focus. In the course, Professor Gumuscu explored with students the dynamics of threats to democratic systems, using Venezuela, Turkey, Hungary, India, the United States, and the Philippines as her case studies. Together, they asked, “What are the driving forces to the backsliding of democratic systems and the rise of autocracies in the 21st century—including the roles of the political elite, failing institutions, eroding norms, and ordinary people?”

The roles of ordinary people struck a particular chord with her students. Professor Gumuscu reported that her students were incredibly engaged in studying the role of conflict, and the resolution of conflict, in both thriving and struggling democracies. She had students think about real ways to tackle the conflicts they were studying. Gumuscu also remarked how much students wanted to be leaders in this work out in the world. Her challenge to the students was this: “OK, your first piece of work is in our American democracy: go to a Thanksgiving meal and actively facilitate a conversation across political difference that you know will be incredibly hard.” As a result of this experience, Gumuscu is thinking of teaching a follow-up course, How to Save Democracy, which will look at case studies where conflicts large and small were mediated and democratic systems were preserved. Her students’ wish to be out there in the world inspired this idea.

So, this year we have been learning together about what higher education can do to revitalize our democracy, one conflict at a time. Democratic leadership is the capacity to facilitate different viewpoints, and live with conflict, and then transform it so that its trajectory is positive. That is what makes democracy real—the ability to engage opposing perspectives with skill, rigor, and compassion.