In 2012, a 29-year-old oil worker named Kristopher “KC” Clarke went missing from the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota. At the time, he was working for Blackstone, one of the white-owned companies that had recently gained access to the prairie’s oil-rich shale through the advent of fracking.

For Sierra Crane Murdoch ’09.5, Clarke’s disappearance embodied the dark side of the oil boom transforming the reservation, which she had spent the previous year reporting on. Crime was on the rise, she noticed, in large part because the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation—the three affiliated tribes that populated Fort Berthold—had no criminal jurisdiction over the throngs of white outsiders looking to get rich off their land. By determining what happened to Clarke, she hoped to shed light on the violence, greed, and despoliation scarring the reservation.

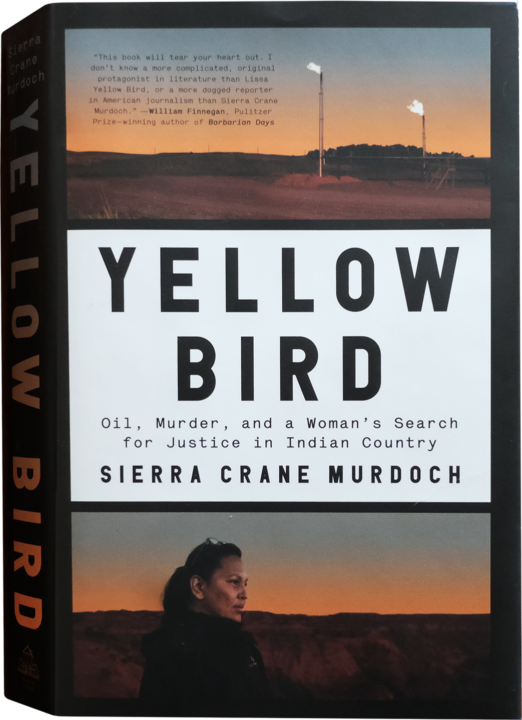

Murdoch wasn’t the only one interested in Clarke’s disappearance: in 2014, she met Lissa Yellow Bird, the key source, driving force, and flawed moral center of her captivating new book Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman’s Search for Justice in Indian Country. Lissa is as iconoclastic and compelling as any antihero ever to star in a work of nonfiction. She’s a whip-smart recovering addict who spent two years in jail for possession of meth; a prickly but loving single mother of five children, two of whom she once proposed killing rather than sending them back to the abuses of foster care; a proud steward of native culture who has worked as a bartender, a stripper, a carpenter, and a welder; and a relentless amateur detective who helped solve the Clarke case through savvy use of social media, fake identities, and bald manipulation.

Murdoch wisely chose to build Yellow Bird around Lissa. Though it works well as a pacey and suspenseful murder mystery, the story gains piercing depth and nuance through the lens of Lissa’s experience. She becomes a much sought-after expert in finding people who go missing from the reservation—and a shocking number do, most of them indigenous women—and her quest sharply illuminates the injustices the native population still endures at the hands of the government and nonnatives. In an author’s note at the end, Murdoch shares her trepidation about being a white woman telling this story. But ultimately, what prevails is the intimacy of her partnership with Lissa, the obvious trust accrued over months and years of searching for the same truth.

Leave a Reply