by Elizabeth Fink Farnsworth

When Elizabeth Fink Farnsworth ’65 is nine, she returns home from a sleepover to find her father crying in the bedroom. “We lost Mother last night,” he tells her. “She’s gone.” Though Elizabeth knows her mother has been in and out of the hospital, and has even seen her “purple scars where breasts had been,” she can’t quite fathom what he means. “She’s gone somewhere for reasons we don’t understand,” she tells her stuffed bear, Louie. “We’ll find her—I promise.”

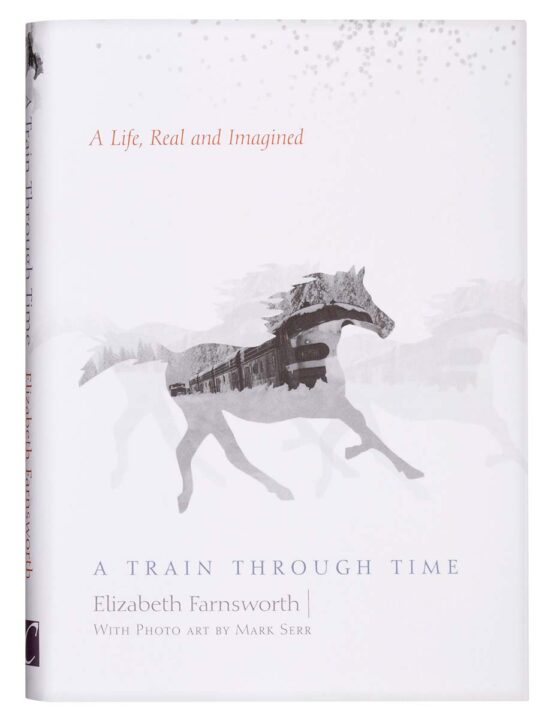

In her affecting new memoir, A Train Through Time, Farnsworth strives to understand not only the mystery of her mother’s death but also the way it shaped her career as a filmmaker and foreign correspondent. Reporting for PBS from places ravaged by war and tyranny—Pinochet’s Chile, post-Khmer Cambodia, Haiti under military rule, a scorched Vietnam—she is drawn to stories of grief, resilience, and redemption. Am I most comfortable on the edge of loss? she wonders. Brief, disconnected scenes from these reporting trips intermittently punctuate the central narrative, which follows her and her father on an epic train trip from their home in Topeka to California, a destination that resembles the Oz of the Frank Baum books she reads along the way: colorful, verdant, restorative. Peering out the window, Elizabeth studies every face they pass, searching for her missing mother.

Their six-day journey proves both cathartic and highly eventful. Somewhere between Utah and Nevada, Elizabeth’s father apologizes for all the euphemisms and tells her what happened. “It was the first time anyone had used the word dead when talking about my mother,” she writes, in one of the book’s most powerful scenes. Fortunately, there are plenty of distractions on the train: she and another girl discover a shuttered car carrying a spirited white horse. The train gets stuck in a blizzard, losing power when it hits a wall of snow. Passengers cut up curtains to keep warm. Food and water supplies dwindle. The air grows fetid. Emergency generators spew carbon dioxide into the berths, sickening passengers.

Anyone paying attention to the slender volume’s subtitle—A Life, Real and Imagined—won’t be surprised to learn in the final pages that the journey didn’t transpire exactly the way Farnsworth so vividly describes it. Though she meticulously fact-checked the snippets from her reporting trips, she explains, she let her imagination remake her memories of the train trip—and help her reconcile her mother’s death. It makes her an uncommonly sensitive and engaging companion for readers along for the ride.

Leave a Reply