When we first meet Alice, she has blanketed her Upper East Side neighborhood with $2,000-reward posters for her missing dachshund-Chihuahua mutt, Maebelle. But Alice seems to have lost more than her dog.

Her grown twins have left home for college in California, her husband Peter is packing for a Memorial Day weekend in the Hamptons without her, and the grant application to fund her work as a biophysicist studying the murmuration of starlings has sat untouched for months.

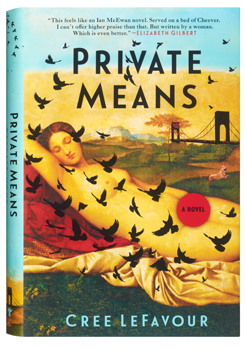

Such is the start of summer for Alice in Private Means, a debut novel by Cree LeFavour ’88. Though this is her first work of fiction, LeFavour is known for a series of award-winning cookbooks as well as her incisive 2017 memoir, Lights On, Rats Out.

“She’d lost track of herself entirely in becoming a thing she’d never dreamed she’d be,” LeFavour writes of Alice. Whether that thing is being a mother, a wife, or an unhappy person, Alice never quite clarifies. We know more about the designers Alice wears—the Stella McCartney jumpsuit, the Emile Pucci bikini, and the La Perla lingerie set—than the waiflike woman who inhabits them.

LeFavour offers alternating narratives from Alice and from Peter, almost as if it’s the conversation they can’t seem to have. Instead, Alice has an impulsive one-night stand that she imagines into a full-fledged relationship before realizing that the man is not at all interested—another disappointment. And Peter becomes dangerously close to acting on a puerile fantasy with a particularly vulnerable patient. They have their lonely interpretations of what’s happening to them as a couple, their separate reckless actions, and their predictably consequent angst.

Throughout the summer, they visit friends and family as they make the weekend rounds escaping from the city. They even visit central Vermont, and LeFavour sneaks in a reference to the much-loved local “creeme,” which will no doubt delight her fellow alumni enthusiasts as much as it fosters the ongoing arguments over its correct spelling.

It’s finally a close friend and fellow psychiatrist who helps Peter, and eventually Alice, step away from their self-propelled solitude and begin to empathize with what the other might be feeling. It’s a slow start to healing and, at last, more than a little hopeful.

Leave a Reply