“My internist, who is also a very, very close friend of ours, she called and said, ‘You don’t sound good.'”

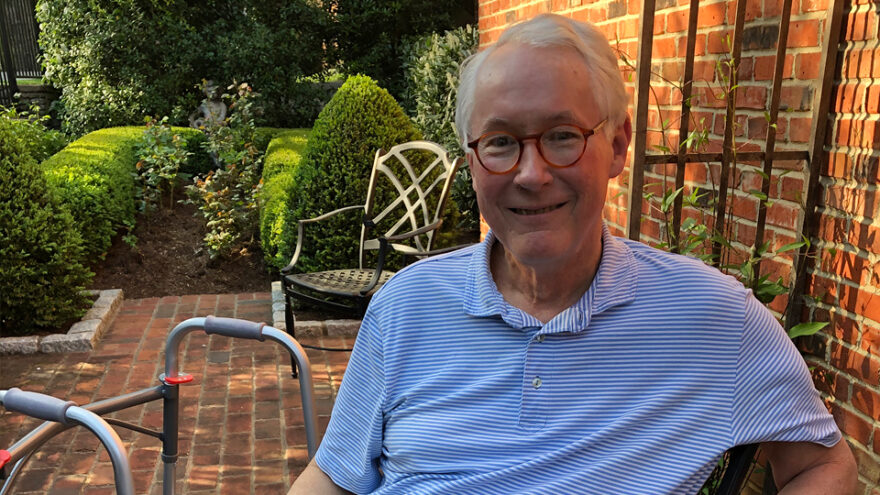

—Dick Clay, Bread Loaf student and Covid-19 survivor

Laurie Patton:

You’re listening to Midd Moment. I’m Laurie Patton, president of Middlebury and professor of religion. In this special series, I’m checking in with our community to see how people are doing so that we might get a better idea of what it’s like to be alone, together.

Today I’m speaking with Dick Clay, a Bread Loaf student who recently recovered from COVID-19.

Dick Clay:

My name is Dick Clay, and I am entering my third summer, which will be the summer of writing, which I will do here in Louisville, Kentucky. By training, I’m a lawyer with 42 years of experience.

Laurie Patton:

Dick, thank you so much for joining us. We’re so glad you’re healthy, and we’re so glad that you’ve been able to be with us. How are you feeling? How are you doing today?

Dick Clay:

Well, I’m standing up as we speak, and I’m perfectly vertical. I’m in great shape. I’m walking two or three miles a day, fast. It’s just an absolutely wonderful, miraculous thing that I’m back.

Laurie Patton:

You’re feeling miraculous because you, in fact, have suffered from COVID.

Dick Clay:

Yes.

Laurie Patton:

Tell us a little bit about your journey, story. How did the story of COVID-19 begin for you?

Dick Clay:

I chaired the board of the Speed Art Museum here in Louisville. Every year, the first Saturday in March, we have a ball. This was the ball on Saturday, March 7. My wife and I went, and I remember at the ball that night, people were doing the elbow bumps and all of that, but I don’t think anyone really took it seriously. We are pretty sure we were exposed there.

Laurie Patton:

So, you got home from the ball, you had a great night dancing.

Dick Clay:

Yeah. The symptoms came a week later. And I felt like I had a fever. Elizabeth, my wife took my temperature. It was 102. It really didn’t occur to me that time that I was COVID positive. For the next 10 days, I was home with a fever the entire time. We were fortunate in that my wife and I have some good doctor friends and one of them got us into testing that afternoon. The test results, for me, didn’t come back until I already was in the hospital. We were both positive. Elizabeth was asymptomatic the entire time, with the exception that, ultimately, she lost her sense of taste and smell. The fever, some slight coughing, and then an increasing feeling of a lethargy, I think were my primary symptoms. I found out I’d lost taste and smell when after talking to my internist, she said, “Well, stay home and self-quarantine.” I couldn’t smell or taste all the bleach products we were using to clean our house.

Laurie Patton:

Wow. So you were at home for 10 days, feeling like it was a kind of flu-y thing. Then, you got to the hospital because your condition worsened?

Dick Clay:

Yes. My internist, who is also a very, very close friend of ours, she called and said, “You don’t sound good.” This was on March 24. I said, “Oh, I’m sure I’ll snap out of it.” She says, “What about shortness of breath?” I said, “Well, when I walk up the stairs, I feel a little winded at the top.” She said, “You need to go to the hospital.” She said, “I’m going to talk to Elizabeth.” So, she called Elizabeth downstairs in our basement, who was at that time, making a quilt on our pool table. Elizabeth came upstairs with tears in her eyes and said, “I need to take you to the ER.” So off we went, and suddenly, the enormity of it all hit me.

Laurie Patton:

Hit you, yeah.

Dick Clay:

I was feeling so badly a couple of days earlier that—I had so much time on my hands—that I thought, “Well, Elizabeth has always asked me to write my obituary or at least give her a rough draft of it,” so that was on my to-do list. So, I just did it. But it didn’t totally register with me or occur to me that I could possibly die.

Laurie Patton:

Were you put on the ventilator right away when you got there the first time, or did your condition worsen over your stay in the hospital?

Dick Clay:

I went from the emergency room to ICU. I remember they gave me a cheeseburger, and I was so happy. It was delicious. So, I must have been hungry. I spent the night in ICU and then the next morning, an anesthesiologist came in, Dr. Cheryl Callins. Dr. Callins said, “We’re going to intubate you.” My reaction was, “Well, I have no choice. You’re in charge and that’s fine.” I said, “Can I call my wife? Can I call home?” They said, “Well, we don’t really have time, but we’ve called her already and we’ll call her again.” I thought, “Oh, I’m a bit player in this drama.” For the next seven or eight days, it seems to me as if it was a bit of a blur.

Laurie Patton:

In your narrative we went from shortness of breath at the top of the stairs, to going to the hospital, to needing to be on a ventilator. Did you experience a shortness of breath so dramatic that you needed to be on the ventilator, or were you thinking, “We’re all okay,” but they put you on the ventilator anyway?

Dick Clay:

That’s what I thought. The shortness of breath creeps up on a person so that he or she gets so used to it, that they don’t notice it.

Laurie Patton:

Six or seven days, you were on a ventilator, initially. Then, you came off the ventilator when you woke up.

Dick Clay:

I was on the ventilator for two or three days. Then, they wanted to see if my oxygen levels had stabilized. If I was in—the optimal oxygen is 95 percent or over. I had been down in the 80s, which is a bad, bad thing. So, they took me off the ventilator. They still had oxygen tubes going through my nose, but again, the oxygen level fell. So, the next morning they put me back on the ventilator. I was off the ventilator just overnight. Can I say a few things about the doctors and the staff?

Laurie Patton:

Of course. You can say anything you want.

Dick Clay:

The doctors who treated me were young. So, if you have students at Middlebury who want to be doctors, this is a word of encouragement because these young people, and I can say young, I’ll be 69 in July, were superstars. They would come in and talk to me. They, of course, had masks. They had rubber gloves, but they both did not hesitate to hold my hand. This is very emotional. They are at home with young children and they’re all frontline. They’re all very, very brave, and they’re not paid what they’re worth, and they can never have adequate recognition.

Laurie Patton:

Yeah. You went through this and you were kind of, it sounds like, in a haze. Then, there was a point at which you felt that you were ready to move out of the ICU and recover. So, probably my guess, you can tell me if this isn’t the case, that the seriousness of the situation maybe only hit you when you started to recover.

Dick Clay:

That’s wonderful perception on your part. They let me bring my notes from ICU out with me. I feel fortunate that they did. They’re all in pencil. Remember, I couldn’t talk because of these feeding tubes and the ventilator stuff all going down my throat. I couldn’t talk, but they would let me write questions in ICU. The one question is, “Will I live,” question mark. That was the one that is, perhaps, the most telling about my state of mind. It’s some time in that blurry period. You’re talking to a litigator of 42 years training. Lawyers don’t tell their clients they are going to win. You can encourage them, but you don’t want to get their hopes totally up, in case there’s a result that is not what you or they expected. So, these doctors were doing the same thing, and the nurses. I think one of them told my wife, “We’re cautiously optimistic.” Anyway, off to recovery, I went. That had its own new set of learning opportunities.

Laurie Patton:

There’s a wonderful phrase, that I used in a letter, that was penned by a Midd alum, called the “wilderness path of recovery.” It’s almost as if we’re experiencing this now, all over the country, that the practice of recovery is almost as disorienting and hard as the actual pandemic. So, tell us about that.

Dick Clay:

The wilderness experience. I learned the simplest little things have meaning in a recovery room. For somebody who took a Centrum Silver and a Vitamin D pill every day, and that was my total medication going into the hospital. All of this was a new and different experience. Bed pans. I’d never had a bed pan in my life, and moving and being moved so I wouldn’t get bedsores. I couldn’t get out of bed. Plus, I was exhausted. I hadn’t moved, and I’d lost 16 pounds. In recovery, my feet wouldn’t bear weight. None of the rehab centers, at that time—this was sort of early in the COVID game—wanted to take COVID patients. They were scared of us. It’s the first time I’ve ever felt I’ve been—I mean, look at me. I’m Mr. White Male Privilege. I’ve never been discriminated against in my life, but I suddenly was feeling like, “What? They won’t let me come in their doors? What’s this all about?” So, that was an interesting experience. The way we took care of it was, Dr. Kelly said, “Oh, do you think you need to stay another two days?” “Oh, yes, Dr. Kelly, I do.” “Done.” That made all the difference in the world because then I was able to walk with the assistance of a walker.

Laurie Patton:

Part of the heartbreak of this experience for people is that you’re in isolation. When did Elizabeth—she also had it—when did you finally see each other?

Dick Clay:

A van brought me home on April 8 from the hospital. Unfortunately, for my frail ego, it was the day before they started playing “Here Comes the Sun” by the Beatles, with all the nurses outside clapping for you as you left the hospital.

Laurie Patton:

Oh, so you were an unsung hero?

Dick Clay:

I was a unsung hero.

Laurie Patton:

For the last part of our conversation, Dick, I want to ask you about your writing and ask you about Bread Loaf. You’ve made a career move to do this after a long career as a litigator. Tell us, are you going to be writing about COVID for Bread Loaf this summer?

Dick Clay:

Yes, I am. What I want to do is write about my COVID experience in the form of prayers and meditations. I started this with a creative, nonfiction course or tutorial that I had in the summer of 2018 with Gwyneth Lewis. Then also, that summer, I was taking modern British and American poetry with Michael Wood. They’re both splendid teachers.

Laurie Patton:

Yes, indeed. How are you structuring your prayers and meditations for your writing this summer at Bread Loaf?

Dick Clay:

A passage from the Bible, either the Hebrew Bible or the New Testament. Then, I would write about an experience I had that was informed by that passage. Then, I would end it with, generally, a brief prayer or something from someone smarter or a better writer than I. What I want to do is take this experience and put it in the context of poetry by John Donne and George Herbert, who both wrote during times of plague.

Laurie Patton:

What I’m interested in, in particular—because I knew about your engagement with the Filson Historical Society. I grew up in Danvers, Massachusetts, formerly known as Salem Village. My folks were very engaged in the local historical society. I’m interested in whether a kind of local history of the experience of COVID during this time might be something you’d consider working on.

Dick Clay:

Definitely. The Filson already is collecting in any way we can get it, written forms, either in handwriting, emails, whatever. One thing that’s informed all of this is we have a pretty extensive collection of the pandemic in 1918. We have pictures. We have writing from that. It’s been very telling to look at that history as compared to what we’re doing now.

Laurie Patton:

We also feel that your joining us at Bread Loaf is two reasons for celebration. One, it’s good for Bread Loaf. But, the other is that it’s a sign of great vitality and love of life on your part.

Dick Clay:

Yeah. It’s fun to be the about the oldest person there.

Laurie Patton:

Right, and it’s a sign of your recovery. So, that’s also a reason to celebrate. I wish I could say I would see you on the mountain this summer. I cannot say that at the moment, but I can’t wait to see you back on the mountain very soon.

Dick Clay:

Excellent.

SHOW NOTES

- This episode was recorded before the killing of George Floyd and the weeks of unrest that have followed.

- Slimheart by Bitters via Blue Dot Sessions

- Waterbourne by Algae Fields via Blue Dot Sessions

You can subscribe to Midd Moment: Alone Together at Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or Spotify. We encourage you to do so today!

Leave a Reply