On a Sunday evening in mid-April, the editors of the Middlebury Campus clicked into frame, Brady Bunch–style, from their bedrooms and dining room tables and makeshift home offices. Editor in chief Sabine Poux, a bespectacled senior with a wave of dark hair, logged on from Westchester, New York. Managing editors James Finn ’20.5 and Bochu Ding ’21 jumped into their rectangular boxes from Mississippi and San Francisco, respectively—Finn bracketed by an old-fashioned headboard, Ding offset against a blank white wall.

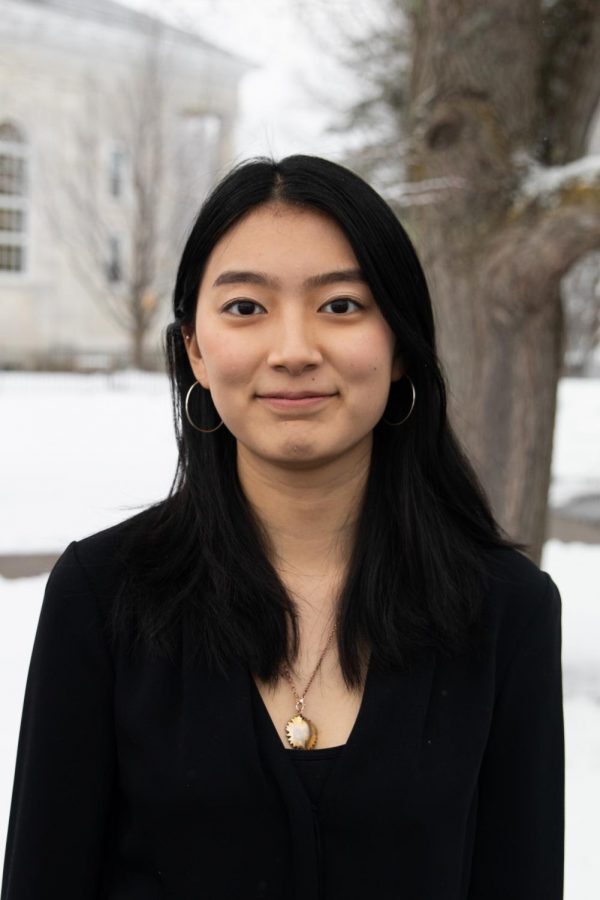

Once on-campus classes were cancelled in mid-March, the work of producing a college newspaper became a globe-spanning operation, with student editors forced to work from their childhood bedrooms (or wherever they might have landed for the duration). There’s an opinions editor, Jake Gaughan ’22, in Honolulu. Arts and academics editor Rain Ji ’23 is working from her home in Beijing, China, five hours ahead of her colleague Elsa Korpi ’22 in Finland. On that particular Sunday night in April, Ji was backlit by early morning Beijing sunlight; on the East Coast of the United States, editors flicked on overhead lights and desk lamps against the growing dark.

Since 1905, the Middlebury Campus has been the continuously published record of student life at Middlebury College. This spring, under Poux’s leadership, the 115-year-old institution was, for the first time, producing that newspaper entirely remotely. (Full disclosure: I was editor in chief of the Campus in 2007–08.)

When the College ended in-person instruction in March, roughly 120 students who could not safely get home remained on campus in Vermont; the rest of the student body, including the entire editorial board of the Middlebury Campus, decamped to ride out the COVID-19 pandemic at home, with friends, or in lodging cobbled together in the frenzied days and weeks after the campuswide shutdown.

Earlier in the semester, these student journalists would have congregated for their weekly Sunday editorial meetings in the basement of Hepburn Hall. No longer, as a virtual reality took hold, with the students gathering instead via Zoom on Sunday evenings to discuss their editorial planning. And this, it turns out, has been the easy part: Slack messages and emails, texts, and Google docs. The logistics aren’t necessarily complicated for digital natives.

The harder part? Figuring out what it means to cover a college in diaspora, a tight-knit community disbanded to the corners of the earth. Amid the churning global news cycle surrounding COVID-19 and, later, national unrest over police brutality, the Campus editors have gone to work—reporting on students struggling to get home from far-flung study abroad programs, diving into the complexities of grading classes conducted remotely, surveying student opinions on returning to Middlebury next year, and capturing the range of student activism following the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

They’ve written about academic equity and staff wages, student vandalism and business layoffs in the town of Middlebury, protest marches in Vermont, and tension surrounding the unwelcome return of some seniors on what would have been the weekend of their graduation.

“In the beginning, we were trying to give people information that they felt they didn’t have, and we were realizing how important it was to represent as many perspectives as possible,” said Poux. “We want this to be a place for people to be connected to Middlebury again.”

A handful of classmates stood at the front of the room, giving a presentation in Spanish, largely oblivious to the mounting drama.

“It really was totally out of the blue,” said Finn, recalling the semester-shattering news—on Tuesday, March 10—that Middlebury College was sending students home for what would turn out to be the end of the spring semester. Finn had spent the weekend prior worried more about classwork and deadlines than a global pandemic. But by Monday night, the mood on campus was starting to shift—dramatically so, by Tuesday morning.

Poux’s sources began reaching out early on Tuesday, warning that an announcement might be coming later in the day. A faculty member had inadvertently leaked the news first, forwarding to two of his classes an email announcing the school’s intention; that email spread like wildfire across campus.

“I was in class at 11 a.m. that day, when that email started circulating,” said Finn. It was chaos. “Everyone was checking their computers, seeing these screenshots that were going around.” A handful of classmates stood at the front of the room, giving a presentation in Spanish, largely oblivious to the mounting drama.

“It felt like in the space of 10 minutes, Middlebury was sort of over,” said Ellie Eberlee ’20, the senior opinion editor, who was in the library. “The jig was up. People were leaving their thesis carrels. . . . A bunch of people up and went to the bar.”

Soon, Finn, Poux, Ding, and senior news editor Cali Kapp ’21 met at Atwater Dining Hall, snagging food before finding a corner in which to talk. Looming above their personal circumstances—how would they get home? where would each go? what about their stuff?—was the question of the newspaper.

“One thing that James, Sabine, Cali, and I felt really strongly about was that we needed to get it right,” said Ding. “Anything that we published had to be accurate and wasn’t introducing more chaos into whatever situation that was. I felt as if that day we really clearly defined what we were as an organization and our role, which was to provide clarity.”

It was Finn who framed the angle: they couldn’t yet confirm the College’s plan, but they could write about the leaked email’s existence and the ensuing tumult on campus. They published a story a few hours prior to the College’s official announcement that afternoon.

Then came the next question: Would the Campus go to print as usual, as it had on every Tuesday night in the years prior? At that point, students believed they had just over 72 hours to leave campus. (That deadline was eventually extended by two days.) Many students skipped classes for the remainder of the week, toggling between the logistics of getting packed and home and the desperate desire to spend time with friends. Could the Campus leadership ask its staff to go to work? Texts began flying among editors: “Are we supposed to be in the office in a couple of hours?” “Are we still doing this?” “Are we still publishing?”

But cancelling the issue felt like “throwing in the towel,” said Poux. “‘School’s over, we’re giving up, fuck it.’” She felt a responsibility to the historical archive to produce a physical record of the largely unprecedented news of the week. Personally, she wanted a sense of closure. Yes. They’d publish.

The days that would follow, Poux said, gripped students with a sort of “apocalyptic fervor.” But before that set in, the paper’s leaders made a plan. There was never any real debate as to whether they’d continue their work; the Campus would go remote. And before anything else, they’d put out a newspaper. “We all assumed that it would be the end of us all being on campus,” said Poux.

They worked hard and smart and fast that night, leaving the office around 12:30 a.m.—hours before they usually put the paper to bed.

“I’m really grateful for Sabine’s leadership. I think a lot of us were tired, and to be quite honest, there were moments when I felt like I’d rather not be putting out a print issue right now, I’d rather be with my friends who are graduating,” said Finn. “[Sabine’s] vision really guided us.”

And in the end, at the conclusion of a “really, really nightmarish” week, said Finn, “it felt really triumphant to put out that issue.”

Poux’s time at the Campus had been bracketed by two unexpected, newsworthy maelstroms. She ended her tenure navigating a virus that had pushed the paper, and College, into uncharted territory. The first, though, came in her first-year spring, shortly after she joined the editorial board as an arts editor. The controversial social scientist Charles Murray was slated to speak at Middlebury; the protest and weeks of news coverage that followed threw the community into the national spotlight.

“We had so many great conversations as a board in that room,” Poux said. “The Sunday editorial meetings were really special, and we got close because we were having to cover that and deal with the terrain that came with Charles Murray.”

It was a coming of age for the writers at the paper at that time. In the wake of the Murray event, the Campus turned to Jason Mittell, professor of film and media culture, to take on the role of faculty advisor. Mittell watched as Campus editors grappled with a new sense of themselves as journalists. “That was the first moment that the Campus realized that because they had a digital platform, they would be read beyond just the immediate physical community,” said Mittell. “That led a lot of students out there to up their game. The fact that they had that experience of being in the spotlight, and learning how to create work that was ready for consumption on a short turnaround and publish outside the weekly schedule—that really primed them to thrive in this moment.”

In the intervening years, the Campus staff has taken on a series of ambitious projects. Digital director Amelia Pollard ’20.5 began overhauling the website in 2018. In 2019, the team launched “Zeitgeist,” a massive survey of the student body that used data visualizations to share opinions and demographics on a wide range of topics. Increasingly the newspaper reported on issues around staff, including on the topic of salaries and morale—a story no one else was covering.

Poux was poised to come full circle: the College Republicans issued another invitation to Murray in January. Senior news editor Kapp remembers sitting with Finn and Poux as the Campus prepared to break that news.

“All three of us looked at each other. ‘Is this really happening?’” said Kapp. The senior editors spoke at length about how to cover Murray’s planned March visit without overshadowing the rest of the semester. “Murray’s visit is big, no doubt, but there is more to Middlebury than that visit,” wrote Poux in a missive to the community. “If you’re looking for clickbait, look elsewhere.”

It was good training for the conversations that would come as COVID-19 upended campus life, scuttling the Murray visit and threatening to drown out all other news.

“I think this spring, [between] Murray and . . . all these crazy events that have spiraled out of control, it’s given us a really good set of tools to deal with crises,” said Ding. “It’s given us a new lens through which we can understand reporting. What matters? What is the most essential thing to cover? How can we serve as a platform for people’s voices?”

For some people, I think it’s been cathartic to pour all of themselves into this,” said Poux.

With the last print issue put to bed, it was time to—as the posters around campus urged students to do—“box, label, and leave.” Poux drove back to her family’s home in Westchester, New York. It was an easy trip compared to those facing some of her colleagues. Opinions editor Gaughan petitioned to stay on campus, but hopped an 11-hour flight to Honolulu when his request was denied. Ji drove to Montreal with friends, boarded a plane to Beijing, and spent two weeks at a medical quarantine facility.

“I think there was always a kind of mutual understanding that we would continue to work remotely, just because there is so much news coming out of this and so many stories that need to be told right now,” said Finn. But senior editors were gentle with one another and their section writers; they made it clear that if anyone was overwhelmed, it was perfectly acceptable to take a step back from the work. Very few did.

“For some people, I think it’s been cathartic to pour all of themselves into this,” said Poux.

Eberlee recalled logging on for the first virtual meeting on Zoom during that two-week spring break. “When we all Zoomed in, that was like the greatest thing that had ever happened,” said Eberlee. “We sat on Zoom for 2 hours and 40 minutes and no one wanted to hang up.”

The meetings served as a social respite in a time of social distancing, a glimmer of the greater College network that once existed in dining halls and library greetings. “The paper this year has been a much more cohesive, open social space. It feels particularly welcoming socially now,” said Finn—something he credits entirely to Poux’s leadership and encouragement.

And there was no shortage of news to cover. Vandalism on campus spiked in the final days of the aborted semester, leaving bikes lodged in trees and government traffic signs ripped from the ground. The Admissions Office admitted a record number of students. College administrators rolled out an optional “Pass/D/Fail” policy for the semester’s work, kicking off a weekslong debate over equity and how the semester should be graded. The news came down, finally, that the remainder of the semester would be conducted remotely and that an in-person Commencement would not take place. Meanwhile, College staff voiced their concerns and questions to Campus reporters, and editors and writers reached out to local businesses to hear how the shutdown was impacting the town’s economy.

The greater Middlebury community seemed to be responding to the work. Digital director Pollard noted a 400 percent increase in page views on some stories during March over the February numbers. Op-eds flooded in.

“I think people are really grasping for something to maintain their identity as Middlebury students,” said Gaughan, the opinions editor in Hawaii. “Friends who weren’t reading the Campus as much, weren’t engaging with news on campus as much, have really turned to that to maintain their connectivity with their friends and their connection with the College. That’s been really cool to see.”

The Campus is a kind of time capsule for the moving sidewalk of students that progress through the College—so it’s no surprise that the newspaper has always been of interest to Middlebury College Special Collections. It’s a particularly useful way for archivists to capture student experiences, which are notoriously difficult to pin down.

“Students come to college not to think about the past, but to think about their own future,” said Rebekah Irwin, the director and curator of Special Collections. “They’re here with us for this short period of time, and then they move on.” There are diaries and scrapbooks and prints of photographs, but by far the most consistent record of student life has been the student newspaper.

Interestingly, there’s little to no record of the 1918 influenza pandemic in the administrative records of that time. What Middlebury College historians know comes from a student memoir, and from a few notes in the Campus. The College was put under military quarantine on September 30, 1918; classes and social activities were cancelled, though women on campus organized each morning for “drill” and daily hikes. In an October 16, 1918, story, the Campus notes, “It is true that it has taken a sad toll, that of two lives from our number, but, in comparison with the deaths in many other college communities and the localities generally where it has made its appearance, this is the lightest touch.” Come November, the Campus reported on the lifting of the quarantine, and the advent of “moving pictures” in McCullough Gymnasium each Wednesday and Saturday evening.

There’s a term in the collections world—“crisis collecting”—that refers to the act of gathering materials with particular urgency in the wake of a disaster. Poux does have a sense of what she called a “preemptive retrospective look,” and she and her fellow editors are keenly aware that their paper will be a record of this time. In particular, they want to make sure they’re representing as many voices as possible.

In recent years, archives staff have used software to harvest the paper’s digital footprint (in addition to other virtual places of student life, including a popular meme group on Facebook). When the Campus ramped up its remote reporting, “we just kind of turned up the volume,” said Irwin. “They’re thinking about themselves as journalists, not as historians. They should keep doing what they’re doing, and we’ll do our best to have a good record of it.”

As the semester wound down, Poux admitted to having mixed feelings about her final days as a college student. (“I have days when I feel super depressed and days I feel really excited,” she said.) She was applying for reporting jobs, but each day brought further news of hiring freezes, furloughs, and layoffs; like so many sectors in the economy, the journalism industry was getting hammered.

So she focused on some final Campus initiatives that would mark the last days of her editorship. Perhaps the most poignant work to date was the “Off-Campus Project,” a first-person storytelling effort the Campus launched almost immediately after the COVID-19 announcement came down. Only lightly edited, the vignettes share the vastly different personal experiences of the greater College community during the pandemic. The first batch, spotlighting members of the senior class, went live in mid-April.

Among those who submitted stories was Catherine Blazye ’20, a senior from London who evacuated to the UK with her younger brother, a Middlebury first-year. Her father called the two as they sat in the Crossroads Café during their last days on campus, telling them, “Whatever happens, you both need to stick together.”

“That’s when it really did hit me that this was a very serious thing that was going on,” said Blazye. Armed with hand sanitizer and disinfectant wipes, she and her brother headed to the near-vacant Burlington airport to begin the trip home.

Back in Vermont, when the Campus appeared in dining halls each Thursday, Blazye reliably perused each week’s copy. Now she’s a more avid reader online. “I feel like now, more than ever . . . they are really working to bring that sense of community together,” said Blazye. “They’ve done a really good job, and they’re really trying to reach out to the entire student body and include lots of voices. They must be working their socks off.”

There may not be plays to review or athletic events to cover, but the staff was determined to pursue some stories that weren’t directly tied to COVID-19. As April drew to a close, editors put the finishing touches on the second installment of the popular “Zeitgeist” project, and—for a moment, at least—set aside the tidal pull of coronavirus coverage for a special edition: “The Love Issue.” “Chances are, we’re all in need of a little love right now,” wrote the editors. “So we decided to bring you stories about love—and all the good, magical, and downright disturbing ways it manifests at Middlebury.”

The stories covered the queer love scene at Middlebury, a problematic tradition of “screw your teammate” parties, and a feature that tracked the experience of falling in love at Middlebury from the 1950s onward. The editorial board weighed in with recommendations for “socially distant love languages,” and SGA President Varsha Vijayakumar ’20 penned a platonic love letter to the newly dubbed “Class of ’19.75.”

It was a fitting undertaking for the staff of the Middlebury Campus, even in the age of coronavirus. After all, a college newspaper—produced each week by an unpaid staff, atop a mountain of class assignments and thesis requirements—is a labor of love. To report about a place and its people, in all its controversies and foibles and delights, is to celebrate its very existence. Even when that place isn’t so much a campus as it is a loose tether of keyboard and screen.

At the end of one of her last editorial board meetings—a meeting that stretched over two hours as two dozen editors weighed their endorsement of an SGA presidential candidate and debated a new grading policy—Poux concluded the gathering with a kind word to her staff. “I’m grateful,” she told them, thanking the editors for their time and the conversation. She blew a kiss to the screen. “Have good weeks,” she said. One by one, each logged off.

Postscript

I served as the editor in chief of the Middlebury Campus in 2007 and 2008, and in many ways, my greatest education at the College came during long nights in the Campus office. And so, when I reported this story in April, it was with kinship and fondness that I spoke with so many members of the 2019–2020 editorial board. I came away from our conversations deeply impressed by their dedication, their good humor, and their poise.

In June, I reconnected briefly with Bochu Ding ’21, the new editor in chief, not long after Ding and managing editors Hattie LeFavour ’21 and Riley Board ’22 made the unusual decision to continue reporting over the summer holidays. “None of us even blinked,” said Ding. “It just feels like we can’t stop during the summer, because there’s just going to be so much pertinent information coming out.”

They spent the first weeks of the summer reporting on student and local reactions to the George Floyd protests sweeping the nation, and Ding, LeFavour, and Board penned an editorial addressing the role of the newspaper in amplifying Black voices. Data reporting shed light on students’ off-campus experiences during COVID-19. Meanwhile, editors were still waiting for an announcement, slated for late June, addressing the question on everyone’s mind: What will happen this fall?

Even if all of the Campus staff returns to Vermont in the fall, Ding knows they’re in for an usual year. The crowded, cozy editorial meetings in Hepburn Hall aren’t conducive to social distancing, nor are the marathon editing sessions before the paper goes to print. He’s taking it a week at a time.

“We’ll figure it out,” Ding said. “We always do.”

—Katie Flagg ’08

Leave a Reply