The day would begin like most any other in Collinwood, Ohio, a rapidly industrializing suburb of Cleveland. Its 8,000 residents would rise on this morning of March 4, 1908, with most of the men trudging off to work in the railyard that dominated the town or in the foundries and steel mills that had sprung up along the tracks.

Mothers would shuffle their children off to school, to the stately three-story building—just six years old—with its impressive masonry façade, its arched doorways, its high windows. The children, about 370 or so, would trundle into the Lake View School, their footsteps and laughter echoing throughout the building as they tramped across the yellow pine floors—floors that gleamed due to the kerosene used to clean and polish them—and rushed up and down the grand, open front stairwell that rose from the basement all the way to the attic.

Lake View School was aesthetically impressive to behold; only later would the architects of the building admit that it was designed for tragedy.

At some point that morning, there was a spark. That spark led to flame. And that flame led to conflagration.

The school had just two exterior doors; one was blocked by fire, which left a lone opening to serve as the main point of egress for the nearly 400 inside. First responders—mainly the parents of the schoolchildren, who rushed to the building as word of the fire spread—would later speak of desperate attempts to free children from the massive pile of bodies that filled the only exit.

There was no hope to extinguish the blaze. Though there were plenty of cars in 1908, Collinwood’s fire equipment was still drawn by horses, and when the fire broke out, the town’s service animals were hitched to road-grading equipment, smoothing dirt roads more than a mile away. By the time the volunteer fire department arrived, it was too late to do anything but stare in horror. Less than an hour after the first spark, the fire in Collinwood had brought down the Lake View School.

Though some bodies were impossible to identify, town officials ultimately declared that 172 children, two teachers, and one rescuer had lost their lives in the fire. Most of the deceased directly corresponded with the changing demographics of the industrial boom town: 85 percent came from families who had moved to Collinwood since 1900; 79 percent of the victims had fathers who worked in the railroads, in factories, in construction, or as day laborers; and 64 percent of the victims were from immigrant families.

In the days that followed, local and national media amplified the tragedy. Sensationalist headlines screamed (“ONLY ASHES OF DEAD NOW IN THE FIRE’S RUINS,” the Cleveland News; “170 CHILDREN DEAD IN FIRE: Penned in Death Trap in School, Little Ones Are Killed by Scores in Sight of Their Parents,” Boston Post). Teachers—seven of whom out of nine survived—were both lionized and scrutinized. The lone male in the building, the janitor, was initially cast as the villain and probable source of the fire; he was ultimately cleared of wrongdoing and emerged as a highly sympathetic character (three of his five children perished in the blaze). Even a movie emerged from the ashes. A Cleveland entrepreneur named William Bullock was one of the citizens who rushed to the scene, yet unlike everyone else, he did so with a movie camera. Bullock owned Cleveland’s first movie house, and he subsequently screened scenes of the horror to captivated audiences.

And then the story of the Collinwood fire began to recede from people’s consciousness. Not all at once, but gradually, until all that remained was a plaque at the site of the former school and some wispy, fragmented memories in the minds of some. By the turn of the next century, hardly anyone—even people in Cleveland—had heard of one of the deadliest school fires in American history.

Newbury was stunned. A Midwesterner himself, the Chicago native had never heard of the Cleveland disaster.

About four or five years ago, Michael Newbury was researching disasters in America at the dawn of the 20th century. The American studies professor was particularly interested in how stories of these disasters—earthquakes, hurricanes, industrial accidents—were told, and he thought that perhaps his research would lead to a book of essays, a cultural history of disasters. He had been spending a little bit of time learning about an explosion at a flour mill in Minneapolis in the late 1870s when a document trail led him to another Midwestern tale, one that unfolded a quarter century later: the Collinwood fire.

Newbury was stunned. A Midwesterner himself, the Chicago native had never heard of the Cleveland disaster, even though the subject matter, the era, even the location were all areas of his scholarly interest. He quickly discovered why this was: the only professional scholarship on the fire is a 20-page pamphlet produced by the Cleveland Public Library in 2008, the Collinwood fire had escaped the scrutiny of scholars for more than a century. So Newbury turned his gaze toward Cleveland.

Collinwood, Newbury discovered, had everything he was interested in. There was the tragedy narrative, of course—172 children incinerated in a preventable accident. But it was also a story of industrialization. A story of immigration. A story of sensationalist mass media. And it was a story that had not been examined or told, at least significantly, in 100 years.

“That’s a rare thing to find.” Michael Newbury and I are talking in my office in late November, and the wan smile he offers when speaking of this unlikely discovery is in keeping with a personality that can best be described as chill. Newbury has slightly sunken eyes, with a shadow of dark rings below each. His hair is tufted and white and never quite in place, though it’s not entirely disheveled, either. He speaks smoothly and is quick to laugh, though in an understated way. Chill.

He tells me that the more he learned about Collinwood, the more interested he was in that disaster and less keen to work on his other finds—the explosion in Minneapolis, an earthquake in South Carolina, a shoe factory fire in Massachusetts. He says that by the spring of 2014, he was thinking about possibly pulling the Collinwood essay from his collection. Were he to focus not just on the fire itself but also on the greater contexts of the time and place, he would have enough material for a book-length manuscript; he saw potential for a book on an American disaster that had never been written.

At the same time, though, he had just submitted a different project proposal to a new initiative at Middlebury. That year, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation had granted the College $800,000 to support digital scholarship. The newly created Digital Liberal Arts (DLA) initiative featured a faculty fellows program that would provide faculty with funding while they were on academic leave if they used digital tools for scholarship. Newbury had thought he might want to use geographic information systems to analyze and digitally interpret that earthquake in Charleston, South Carolina. When the DLA steering committee responded to his proposal with clarifying questions, he told them he had changed his mind.

“I said, ‘You know, this isn’t actually what I want to do. I’m going to send you a completely different proposal,’” he tells me. “It was after the deadline, but I didn’t care. I figured they could either approve it or not.”

The new project would focus on Collinwood, though what it would be, Newbury admits, he didn’t really know.

While Newbury’s proposal was before the DLA and as he obsessed over Collinwood, he attended an evening screening of films produced by students in the Department of Film and Media Culture. Though he was there ostensibly to watch his daughter act in a short about Abraham Lincoln, he was wowed by another film, an animated piece titled 11 Paper Place. The CGI animation about two pieces of paper that are ejected from a malfunctioning copier, dropping into a recycling bin where they magically transform into paper people and fall in love, would go on to win film festival awards and be honored by the streaming video platform Vimeo. But for Newbury, the film captured his imagination. What if you were to use that medium, the medium of animation, to anchor a scholarly project? He would subsequently bump into Daniel Houghton ’04, then Middlebury’s arts technology specialist and the director of 11 Paper Place. He posed the same question to him, while probing further: What would students be learning? What would he be learning? What product would emerge?

Newbury didn’t know this at the time, but Houghton was, as he would later tell me, “clinging to uncertain career prospects.” His contract had an end date, but he was also presented with the tantalizing opportunity to create an animation studio at Middlebury, at least in name. Though dedicated space for such a studio had not been identified, Houghton was told that if he had students interested in creating animated films outside of a classroom setting, he would be afforded the necessary time and resources to shepherd such projects. “The big risk was, if I couldn’t find anything to do or if I couldn’t encourage student work, the notion of an animation studio would be deemed a failure. At least, that’s what I thought would be the case,” he says. And then along comes Michael Newbury. “And we basically said, ‘Let’s do a thing.’ Whatever that turns out to be,” says Houghton, laughing.

While Newbury and Houghton conversed further, attempting to determine whether they could effectively work together on a project of indeterminate shape and scope, Newbury turned to his colleague Jason Mittell, who had been appointed the faculty head of the DLA. Mittell had been aware of Newbury’s work for some time—he had read several draft chapters of the once-planned book of essays on disasters, he had advised Newbury on his original DLA proposal that focused on the South Carolina earthquake, and he had consulted with him on his first stab at a digital Collinwood project. “I think originally he thought he might want to create a three-dimensional model of Collinwood and have that model be interactive,” Mittell tells me. (For various reasons, the idea of a Collinwood “video game” faded, not least of which had to do with the prohibitive cost of producing a quality gaming experience and the fact that Houghton, Newbury, and a team of recruited students were more interested in film narrative than games.)

“But the core of his concept was the use of animation to visualize disaster. He told me the story of Collinwood, how so little was known of what actually happened, how there were all these sensational, often contradictory media reports, and he believed that a digital visualization narrative could best capture all the complexities of the subject.

“And that’s what excited me the most,” Mittell says. “It was the type of project that was unimaginable without the technology. And it was the type of project that played to the strengths that we have as an institution—in this case, moving images and sound in support of historical research.”

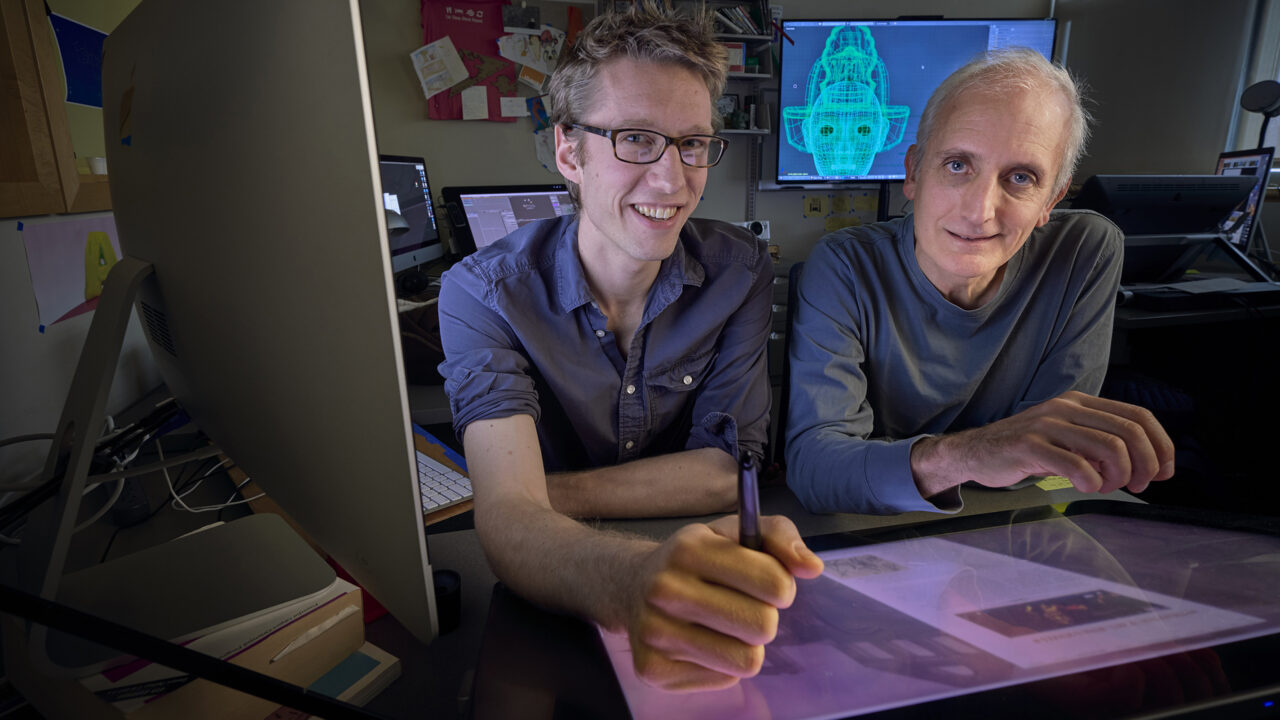

The project that would become “The Collinwood Fire, 1908” was a go. Houghton recruited a team of students fresh off independent projects or animation courses with the flexibility of dedicating a year to one project; and he and Newbury began a series of conversations and debates about just what “The Collinwood Fire, 1908” would be.

When talking to Newbury and Houghton these days, it’s easy to forget that a few short years ago, they didn’t really know one another. Speaking to them in my office one afternoon, they skillfully play off each other, one offering an anecdote that leads into another’s story, or another gently amending one’s recollection of a stressful event in a professional collaboration that has evolved into a genuine friendship. But a couple of years ago? They were essentially strangers, and this was one of the biggest unknowns and critical risks of their endeavor: Would they be able to work together?

The DLA was launched with “the idea that we want to encourage faculty to take risks, to do things they wouldn’t otherwise have an opportunity to do—not just the tools they work with, but how they think,” Jason Mittell says. This ethos of risk taking can be liberating, sure, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that those taking risks are comfortable with the process, especially in the moment. Which, of course, is the point.

For Newbury, scholarly work had always had one constant: solitude. “My mode for scholarly work had always been this: you go into a room, you soundproof it, you put a sign on the door that tells people to leave you alone, and then you close that door,” he says with a chuckle that all but acknowledges he may be exaggerating slightly, but not by much.

“The model for this project was forced human interaction and all that entails,” he continues. “There’s a volatility that most academics aren’t used to. I might want one thing out of this project. Daniel might want another thing. Each student might want their own thing. I remember thinking, ‘Am I really going to want to deal with all of this?’”

Houghton had more existential concerns. “Yeah,” he laughs. “I was asking to work on this one project, asking students to work on this project, for a fair amount of time. If, at the end, it all felt like a failure, whatever that might mean, and this was our first go at it, would I ever get another chance? Or would this all evaporate?” (And by “all” he’s implying his dream of an animation studio.)

And informing all this angst? What Houghton and Newbury were attempting had never been done before. “I think it’s fair to say we were in a form where there were not comparable models to follow,” Newbury says. “Sure, there’s a good model for making animation and a good model for building a website, but these things require expertise that most faculty don’t often have, I certainly didn’t have—managing a team, learning reasonably sophisticated computer coding, mastering the tools of animation. And then all is being employed in the service of historical scholarship.”

He pauses. “There were a lot of places for us to fail,” he says.

The formlessness of the project at the outset—“Let’s make a thing”—which both Newbury and Houghton insist was critical both to the creative process and to figuring out how to work together, gradually began to take shape. “The Collinwood Fire, 1908” would consist of an animated film and a resource-rich companion website.

For so long, I would just sit there and become convinced that it would be impossible to do anything less than a 90-minute film,” Houghton says.

Houghton says that there came a point in the project’s development when he would see what Newbury was producing for the website—Newbury was coding the site himself—and he would be simultaneously excited and relieved. “Knowing that the website existed felt like this safety blanket for the film,” Houghton says. “If we didn’t have a support team in a book’s worth of articles, I think I would have been adrift in the content of the story.”

But this wasn’t always so. For the first couple of months, Newbury, Houghton, and a team of students would meet weekly for what essentially was a three-hour download session, part history seminar and part animation tutorial. (“It was just hanging out, until we were exhausted,” Houghton says. Newbury glances his way and smiles. “We beat each other to a pulp.”)

Newbury would bring drafts of chapters that would eventually make their way to the website. Each essay—on the history of mass media at the dawn of the 20th century, on educational standards of the time, on industrialization—was essential to understanding Collinwood and was something to be considered for the film. “For so long, I would just sit there and become convinced that it would be impossible to do anything less than a 90-minute film,” Houghton says, dropping his head and slumping his shoulders at the memory of the moment.

“I think that might be where—if I were to pick a certain category of disagreement—I would say, ‘Well, there’s this other thing,’ or ‘This needs to be in there,’” Newbury says, as much to Houghton as to me. Houghton nods. “But we figured it out.” And what emerged was contextual. There was the context of the Collinwood story itself—the time, the place, the conflicting stories of what happened that day—the context of the animation as it would exist within the website, and then the context of the entire project. Gradually, everything began to gel.

“The initial walls of suspicion came down,” Houghton says. “And in its place became a trusting, working relationship, where you could make mistakes, inch toward the right path, whatever that undefinable thing is that is better than the last draft in a space where you’re not being judged—”

“You’re being judged,” Newbury says, laughing, “but you really put up with it.” Houghton laughs harder. “Right. Well, a space where you’re not being despised.”

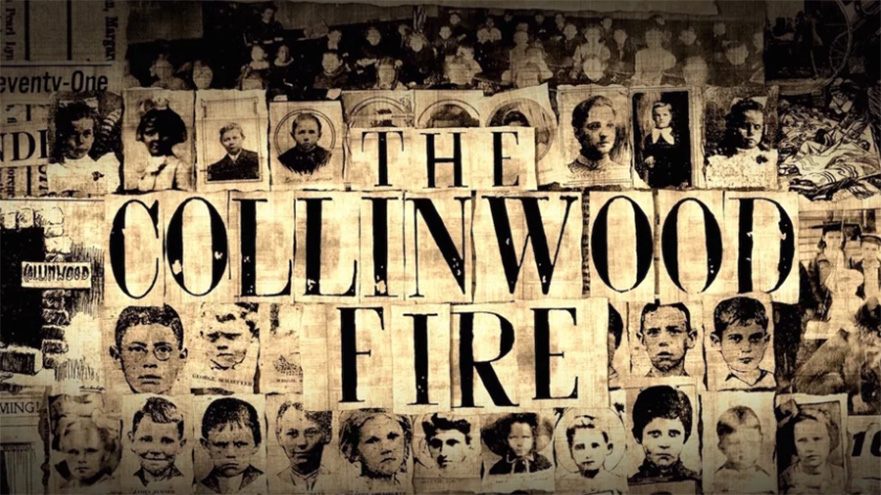

“What did I just see?” That’s the thought I had the first time I watched the animated film The Collinwood Fire. (Please note: From here on, The Collinwood Fire refers to the film and “The Collinwood Fire, 1908” refers to the larger project.) Michael Newbury is pleased when I tell him this, as this is just the prompt the Collinwood team was hoping for.

“Our mantra from the start was ‘Ken Burns on some kind of psychedelic drug,’” Newbury says. “It was never meant to be a documentary, to be seen as ‘real.’ But it was meant to be historical. It was meant to cast you into a place where you had to wonder about the accuracy of the history you were seeing.”

Because that’s at the heart of the Collinwood story, multiple questions with conflicting answers that have been posited over time. Kids playing with matches started the fire. No, the negligent janitor did. The teachers were heroes. No, they weren’t. The doors wouldn’t open. No, the doors were wide open, there just weren’t enough of them, and a stampede occurred.

“The animation,” Newbury says, “calls attention to the unreality of the narration.” And it was up to Houghton and his students to pull this off. I visit him one afternoon in Room 216 of the Davis Family Library. This is now the home of Middlebury’s Animation Studio. Consider it, if you will, the room that “Collinwood” built. After bouncing around from temporary quarter to temporary quarter in the Axinn Center—the corner of a computer lab, the basement edit suite, an overcrowded side edit suite—the Collinwood team moved to permanent digs for the last six months of the project.

The studio has a comfortable, lived-in look with creative flourishes. There’s the well-worn sofa, the large monitors, some toys and clay, the full-length mirror to better study facial expressions. New Yorker cartoons snake around the doorway, storyboards and sketches for current projects are taped to one wall, and there, above the south-facing windows and running the length of one wall, are stills from The Collinwood Fire.

Wearing jeans, a flannel shirt, and black sneakers, Houghton doesn’t appear to be much older than the students he supervises; he certainly looks at home in the space. (And he has a new title: Animation Studio Producer.) We get to talking about the film, and he says that one of the challenges at the outset was helping the students adjust to a different model of storytelling. He explains that most animated shorts function by focusing on “very small, carefully crafted moments. You usually have one or two characters who go through some sort of change, they experience a revelation, and then you’re out. Collinwood was sprawling and epic and didn’t present examples that were easy to show.”

But the team had the time to figure it out—and to determine who was best suited for what aspect of the animation. Houghton speaks about his former charges the way a coach talks about athletes with special skills. Elise Biette ’16 had a background in theater and costume design, and she meticulously researched the clothes of the era and designed the wardrobes. Maddie Dai ’14 designed the buildings, including the introduction of one of the film’s more surreal elements: having the interior walls of the burning school consist exclusively of newspaper accounts of the disaster. Jon Broome ’16, a standout lacrosse player, focused specifically on the movement of the characters. Hosain Ghassemi ’17, a molecular biology and biochemistry major, built a system to control several hundred of the animated characters in crowd shots. James Graham ’15 worked as a prop master—he researched vehicles common to the Midwest in the early 1900s and designed the cars and trucks seen in the film—while also doing a lot of the camera work. (It’s odd to think of animation using a camera, but of course it does, just not in the conventional sense.)

I ask Houghton about the style of the film and how he came to interpret Newbury’s desire for a surreal approach that reflected the sensational storytelling of the day. “In my heart, I feel like a style should boil down to one thing, but this was different,” he says. “Here we had this style collision between what one might call a graphic cartoon style and a historical photograph style.” The style, he says, became that collision. And like everything else in the six-minute film, it is grounded within a historical context. “It is representational,” Houghton says. “It was a time when newspaper representation and filmed images of disaster were colliding, when two worlds of an upper social strata and a lower social strata were colliding. And if this style functions correctly, it’s representative while becoming invisible, as the audience engages with the story.”

So I’ll say this about The Collinwood Fire: It’s magical. While there are conventional characters (most noticeably a newspaper reporter with a conscience and the filmmaker, William Bullock, utterly devoid of one), the main character is place, and not just the locus of the action (the school), but the gritty, exhaust-choked avenues of Collinwood and the exaggerated bright lights of Cleveland, just over the hill. The narrative is riddled with marvelous exaggerations and contradictions—some subtle and only learned about with further reading on the companion website; others hiding in plain sight, such as when one particular action takes place right on top of a newspaper headline that describes the exact opposite of what you are watching. And the sound design by Danilo Herrera ’18 speaks louder and more clearly than any spoken dialogue (of which there isn’t any) would; it will take your breath away, and, more than likely, bring tears to your eyes at the film’s conclusion.

“I have a problem with conventional notions of definitiveness,” Michael Newbury says. He would define “definitive” as a large set of competing possibilities, rather than a magisterial, singular interpretation. This applies not just to the Collinwood disaster, he says, but to the very study of history. If this project does anything, he says, “I hope it encourages people to think of history as a process, rather than a collection of facts. Historical events should be consistently reevaluated, where systemic factors receive just as much scrutiny as proximate causes.”

That’s what you see when you visit the website. The film is there, naturally; it’s the beating heart of the project. But the brain and central nervous system of “The Collinwood Fire, 1908” are the rich histories of the day and place arranged in chapters on the site; they are vignettes, of a sort, each making sense on its own but resonating with the others to form a greater whole. Newbury thinks of them as a series of contemplations. And if one is to ask you what happened at Collinwood, the answer is not kids playing with matches or the janitor running the boiler too hot or even a school poorly designed. The answers are many. They are in the film and they are on the site and they are left for you to interpret.

And here’s the cool thing: that’s beginning to happen. Tara Martin teaches history at Middlebury Union High School. Newbury’s daughter was one of her students a few years ago, and Martin and the Middlebury professor got to talking about the project he was working on. Newbury asked if it might resonate with her students; absolutely, she said. But she was also thinking more broadly and began to research how the material could adhere to state and federal educational standards. Her work is now included on the site under the heading “teaching resources.” Martin and Newbury have subsequently spoken at conferences for social studies teachers in Ohio and Vermont and Boston, and next summer Newbury will travel to Cleveland at the invitation of the curriculum and instruction manager for social studies of the Cleveland Public School system. He’ll be speaking to the city’s social studies teachers about how they can introduce “The Collinwood Fire, 1908” into their classrooms.

Collinwood is being forgotten no more.

I could have ended the story right there, don’t you think? Well, there’s one more person I believe you should meet. Last year, as The Collinwood Fire began to win awards at film festivals around the country, the media began to notice. In October 2016, the story of “The Collinwood Fire, 1908” was featured in the arts section of the Cleveland Plain Dealer. In the days that followed, Newbury began to get emails from people for whom the Collinwood disaster was not an unknown story. He heard from someone who grew up in the neighborhood decades after the fire and who recalled the story being a cautionary tale told by teachers after fire drills. He heard from a descendant of Collinwood’s mayor in 1908. He heard from the great-granddaughter of one of the young girls who survived by jumping out a window. And he heard from a man named Bryan Smith. Smith, who now works at NASA as a director of space flight systems, is the great-grandson of Fritz Hirter. Hirter was the janitor at the Lake View School on March 4, 1908. He was the man who was first demonized and then embraced in the days following the fire. Out of his five children who attended the school, only two survived, one a young girl who would eventually become Bryan Smith’s grandmother.

“I greatly appreciate Professor Newbury’s contextual representation of what was going on in Collinwood in that time and on that day.” I’m talking to Smith on the phone, and he tells me that he’s a third-generation Clevelander. Though he grew up having Sunday brunch at his grandmother’s house, the house she inherited from Fritz, which was a stone’s throw from the former school, his familiarity was distinctly familial. (“My parents’ generation might remember something. My generation? Not really. And certainly not my kids’.”)

He says that as shocked as he was to learn that someone had taken such an interest in Collinwood’s history, he was even more surprised, pleasantly so, that Newbury had put into context things he had never thought about. He says that he immediately shared the Plain Dealer story with a sibling and two cousins, and then he spent the rest of the day and into the night on the website.

The next morning, he contacted Newbury. Attached to the email were scans of some documents that are more than 100 years old. The images are of yellowed sheets of paper featuring a child’s drawings and cursive handwriting. It is schoolwork completed by Helena Hirter, one of the three children Fritz lost in the fire.

These images can now be found on “The Collinwood Fire, 1908.”

Leave a Reply