His baritone voice rose in the fall on home football weekends, resonating across the gridiron and across the decades. Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, please remove your caps . . . He introduced each game when Youngman Field was still young in the 1990s. The deep voice and slow cadence and old-school formality echoed Sherm Feller, the legendary Red Sox announcer who called the games at Fenway Park, just a block from where Russ Reilly’s family owned a printing business. Over years of announcing Middlebury football games, Russ made the phrase his own. Along with the turning leaves, it became for us a signature of the season, an indelible part of our autumn landscape.

In July this past year, Russell L. Reilly passed away from cancer at his home on Dog Team Road in New Haven, five miles north of campus, three days short of his 75th birthday. With everything else Russ Reilly had meant to Middlebury over a 40-year career as coach and mentor and athletic director, the silence reverberated, and reverberates still.

Like Sherm Feller, Russ had a voice built for radio, for announcing. As a father with kids in Middlebury’s community theater, he was, naturally, tapped to play the role of the announcer in Annie, then the booming Nazi soldier in The Sound of Music. But it was when announcing football games that Russ Reilly became full-throated. And the booth, for him, turned out to be the perfect combination of work and play. Though it was a volunteer job just four Saturdays each fall, Russ took the job seriously. He prepared meticulously, writing scripts, learning and practicing the names of the opposing players ahead of time. He was annoyed by visitors interrupting him during his work. He respected the natural rhythms of the game. He’d call the dramatic play in stentorian fashion — . . . the pass is COMPLETE! FOR A MIDDLEBURY TOUCHDOWN!—and then pause, waiting until the cheering had died before recapping the details of the score.

But he never took himself too seriously. He wore a cowboy hat in the booth. He was a big University of Michigan fan and often played a tape of the famous Wolverine marching band over the loudspeakers. He liked to update the Division III scores from around NESCAC and then add, And now some scores from our sister conference, the Big 10 . . . Two or three times a game—not enough to become self-conscious or self-aggrandizing—he threw in unexpected vocabulary that became poetry, as much a part of his signature as his voice: . . . a gaggle of flags thrown on the play . . . where he’s led out of bounds by a pack of Mules . . . swarmed by a congress of Continentals . . .

He felt a professional obligation to call the game right, but he never forgot it was only a game. His longtime spotter, Gary Margolis ’67, remembers Russ’s good humor even as they wedged in shoulder-to-shoulder in the crowded announcer’s booth—and also how Russ sat quietly during breaks in the action to simply take in the sweeping view of the field and Bread Loaf and the Green Mountain range beyond. “Russ said there isn’t a more beautiful stadium for watching football in the fall,” Margolis recalls, “even if you’re sitting on concrete steps.”

Russ carried that big perspective and awareness to his more important roles at the College. He arrived in Middlebury in 1977 to be an assistant men’s basketball coach. As a six-foot-one college player at Bates, Russ had been a mechanically sound but unspectacular player coming off the bench. He had an intelligence about the game, though, and the kind of positive, earnest attitude that made him what coaches call a great practice player.

Coaching was in him. Following Bates, working toward a master’s degree in physical education back near home at Boston University, he served as an assistant men’s basketball coach. He taught earth sciences for a year in nearby Natick, “but he’d run back as fast as he could to BU at the end of the day, to coach,” recalls his widow, Jane. The two had Bates in common—Russ was a senior, Jane a first-year, when they met. They married not long after Russ’s graduation.

“I accepted that sports would always be a big part of Russ’s life,” Jane recalls. “Happily.” They returned to Bates when Russ took a job as a trainer and assistant basketball coach. It was there, taping ankles, that Russ first said aloud his deepest ambition: to be the head coach of a NESCAC basketball team, and someday, God willing, an athletic director.

It took him all of one season at Middlebury to achieve his first goal, when he took over the men’s team from Tom Lawson, who was moving up to become Middlebury’s director of athletics. Russ immediately made a mark on the program. Lawson’s teams had enjoyed a lot of success playing a tightly controlled, methodical brand of basketball. Russ favored the up-tempo style of Indiana’s famous coach Bobby Knight: fast breaking and opportunistic, with relentless, pressing, individually accountable man-to-man defense. Middlebury went from winning games 55–53 to routinely scoring in the high 70s and 80s, and the players had a blast.

As a coach, he was tough and profane. Kevin Kelleher ’80, one of the players on Russ’s early teams, remembers a scrimmage in 1979 when the starters were getting badly beaten by a very physical second team. “I complained to Coach Russ about the constant hacking that was going on,” recalls Kelleher. “And he said in his booming voice, ‘Suck it up and hack back!’”

He preached that rebounding was toughness. In the locker room at halftime during a tense game, he’d yell at his big men, “You’ve got to want the damn ball more than they do!”

John Humphrey ’88 was a hard-nosed four-year starter and captain for Russ. He became the program’s all-time leading scorer in part because of Russ’s run-and-shoot offense.“Two minutes into one game my senior year,” recalls Humphrey, “after a turnover and a missed shot, Coach took me out and let me stew for seven or eight minutes. When he finally put me back in, I was in full rage. I had a pretty strong game from that point on, and we won comfortably. After the game, icing in the trainer’s room, I was still upset. I said to him, ‘What the hell were you thinking?’ He answered, ‘You always play better when you’re pissed off.’ And he was right.”

Russ worked hard over time to rein in his Irish temper, which flared in later years mostly on the golf course. (“I think there still may be a golf club or two floating down the Androscoggin,” says Jane. “And more than one or two up in the trees at the Middlebury course.”) He screamed at referees, flung his sport coat; and one time, notoriously, kicked over a courtside chair. He wasn’t afraid to show his competitive side. “I hate the color purple,” he said more than once. “I don’t want to be anything like Amherst or Williams. Especially Amherst. There’s something about them . . . it just makes you want to knock the stuffing out of them.”

He dedicated himself to preparation. In the summers he worked the circuit of basketball camps, befriending other coaches around the Northeast and picking the brains of the best of them.

But from early on, Russ’s strengths as a basketball coach and teacher were innate. Despite the wide-open style of play he loved, in his own work he was disciplined and detail-oriented—the same way he’d be in the football booth, the same way he obsessed over the cutting of his own lawn, the way he painted houses in the job he took in the summers to help pay the bills.

Years after they graduated, players would recall him as the most organized coach they had ever played for. He ran his practices on time and to the minute. In between game drills, he squeezed in conditioning sets while the boys “rested.”

He was relentlessly positive. One of his daily rituals was walking into the trainer’s room and bellowing, “It’s a great day to be a Middlebury Panther!” No matter how he was feeling, when asked how he was, he answered, “I’m doing amazing!” After games, he didn’t dwell on wins or losses but picked out positive aspects of the play and reinforced them. His optimism was infectious. He believed so strongly in his players that they grew to believe in themselves.

More than anything else, Russ coached the game the way he lived, with humanity and compassion. He preached the importance of teamwork. He talked to his players about their lives, their classes, got to know them off the court. He welcomed them into his house, hosted dinners for them, gave a place to stay to anyone stranded over the Thanksgiving holiday, gave references, opened doors, modeled generosity and the importance of community and personal relationships. Russ and Jane made it a point to get to know the parents of the players and became lifelong friends with many of them. Their daughters were a constant presence in the field house. They made art projects out of blister pads and gauze, kept stats at away games, made the players part of the Reilly extended family. It was all of a piece.

He learned of a local fan named Butch Varno, whose cerebral palsy made it difficult to travel, and became head of a posse that made it possible for Butch to attend games. He helped institutionalize a game-day ritual that became known, simply, as “picking up Butch.” His basketball players became responsible for doing just that for every home football game. The football team, in return, picked up Butch and brought him to Panther basketball games, where he sat behind the team bench.

In time, Russ and Butch created a deep bond, and the players learned something special. Forty-five years after Butch was picked up for the first time, what had been a private local story made national news. On CBS television in 2007, Russ said, “Once you met Butch, you became a friend for a lifetime. For those kids who come from fairly affluent backgrounds at our institution, having the opportunity to go down and pick Butch up in his environment . . . that was a life education they couldn’t get in a classroom.”

Over 19 seasons, Russ coached 433 basketball games, a NESCAC-record at the time. He received a merit award from the National Association of Basketball Coaches for his years of service and was selected by his peers, in 1988, as the NABC Northeast District and UPI New England Division III Coach of the Year. In 1996, Russ achieved his other dream when he was named athletic director, succeeding Tom Lawson for a second time.

As athletic director, Russ oversaw the construction of the Chip Kenyon ’85 Arena, Kohn Field, and a softball diamond, along with extensive expansions and renovations of the fitness center and field house. He staunchly advocated for the role of coaches as educators, ensuring that the “student-athlete” model at Middlebury remained paramount. On his watch, without a whiff of scandal or impropriety, playing the games the right way, Middlebury teams won 35 NESCAC championships and 22 NCAA Division III titles.

When Russ retired as AD in 2006, the same year he was inducted into the New England Basketball Hall of Fame, then president Ronald Liebowitz said that “Russ Reilly has been the understated but essential force” in Middlebury’s program, responsible for setting the tone that defines our values.

His “retirement” gave him the room to work for fun in the pro shop at the golf course—and return to the football booth and the basketball court, where he served as an unpaid assistant coach for the next 13 seasons. His new charge was working specifically with the frontcourt players, “the bigs,” as he called them, and the modeling and influence deepened. He focused on fundamentals, ran the players through old-school Mikan drills and heavy-ball exercises. But he also sensed when they needed to cut loose and when their energy was ebbing. Then his voice would ring out in Pepin Gymnasium, “It’s a little quiet in here! Boys, gimme some thunder!”

And one after another his bigs would drive to the basket and slam the basketballs down through the iron rim.

They called it the thunder drill.

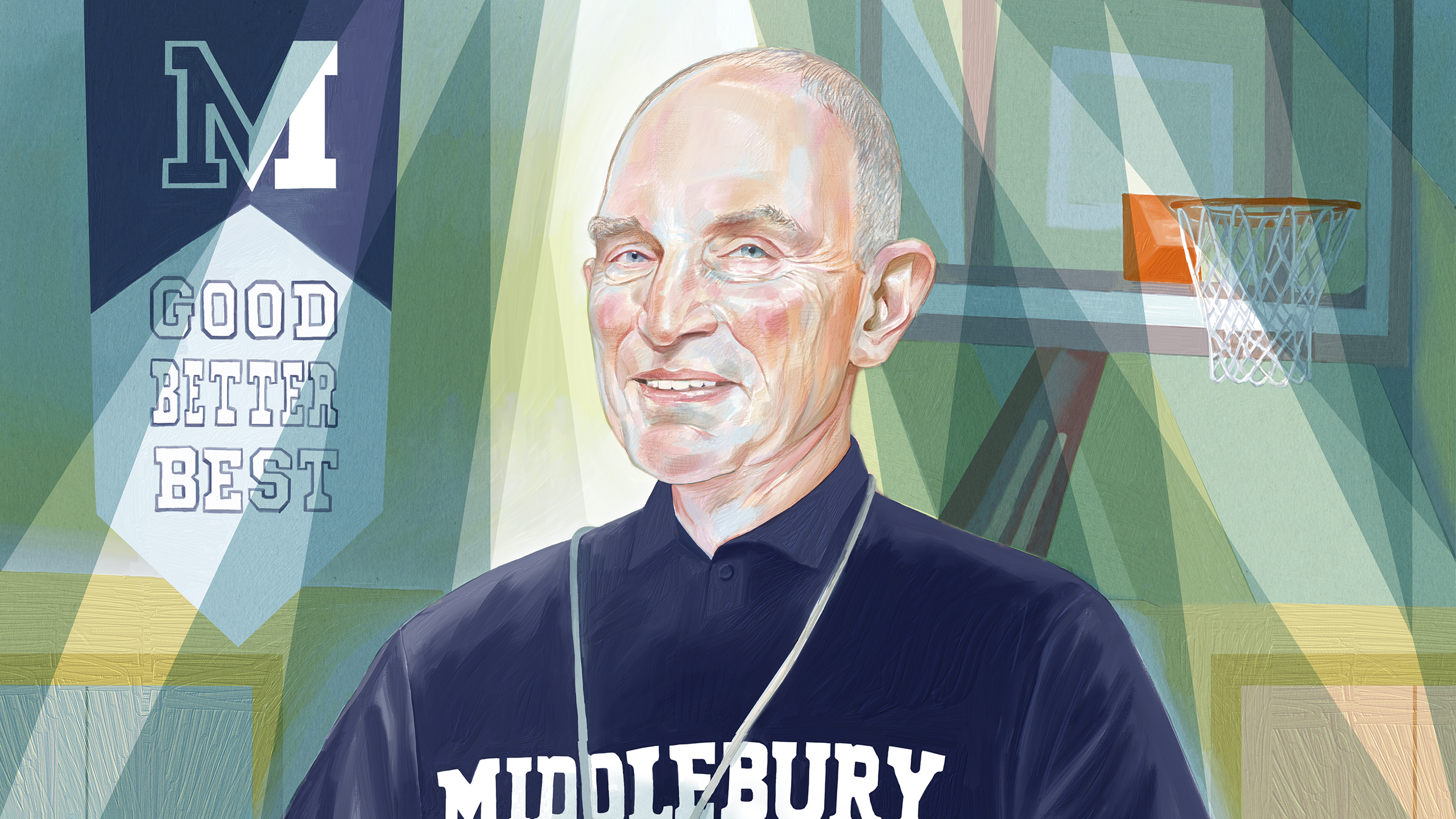

He pulled his bigs together into a tight circle at the end of practices and for pregame huddles, where he often repeated his favorite mantra, Good, better, best; never, ever rest; till the good gets better and the better gets best. From anyone else, the saying might have sounded cornball, but because he believed in them, Russ Reilly’s players took it to heart.

Each February, he and Jane hosted a special dinner at their house and presented the first-year bigs with T-shirts with the mantra printed on the back. When his players graduated and returned to campus, he’d take them down to Mister Up’s, where he knew all the servers by name, and catch up on their lives over a Guinness stout. Another ritual. Alongside basketball, he had weekly breakfasts at Middlebury Bagel with close friends, ate dinners out with the ROMEOs (Retired Old Men Eating Out), and had a regular group of golfing buddies.

There were depths to his character that he kept hidden, perhaps depths that contributed to his humanity.

He was a throwback to an earlier era. He would have fit right into the all-male world of 1950s New England prep schools. “Russ, universally, was considered a good guy,” says Karl Lindholm ’67, one of Russ’s oldest friends, “which means something important to men of a certain generation. But he was more than a ‘hale fellow well met’ who loved his family and his country.”

Russ never spoke of his own upbringing, his mother’s suicide when he was just five years old, the difficult relationship he’d had with his father. There were depths to his character that he kept hidden, perhaps depths that contributed to his humanity.

He also coached 80 varsity women’s soccer games early in his career, and as AD reinforced Middlebury’s commitment to Title IX and women’s athletics, increasing the number of women’s sports at the College to 16, two more than the number of programs for men. He had strong relationships in the department with men and women both. Longtime Middlebury lacrosse coach Missy Foote considered him a friend and mentor. He was close to Sue Ritter ’83, wife of football coach Bob Ritter ’82 and a former Middlebury basketball player. His three children were all daughters—as were two of his grandchildren—and he believed in the power of sports for everyone.

In his final weeks, word of Russ’s condition leaked through the Middlebury community. Ryan Sharry ’12, one of Russ’s bigs, pulled together video greetings and well wishes from former players and their families—an almost overwhelming collection of heartfelt thanks for the difference Russ had made in their lives.

In June, Greg Birsky ’79 took time away from his 40th Reunion to find Russ at the golf course, where instead he learned that Russ was home and not doing well. Birsky bagged the afternoon activities and went unannounced to the house out at Dog Team Road.

“I arrived to a locked screen door with the main door open,” Birsky recalls. “I knocked. The voice boomed ‘Come on in!’ I said, ‘The door is locked.’ And here is the thing . . . Russ heard only those few words and immediately knew who was there. He yelled, ‘Greg Birsky? What are you doing here? It’s your Reunion!’ So there was my coach and mentor, instantly recognizing my voice, knowing it was my Reunion, sitting in his chair fighting and losing to cancer, and all he could think about was how I was missing out on my Reunion festivities. That, in a nutshell, was Russ.”

He passed away at home, surrounded by Jane and his daughters. Cards and emails and phone calls came in from around New England, including from rival coaches and athletic directors who considered Russ a friend. Sue Ritter went down to the Bagel Bakery and sat in Russ’s customary seat for hours, struggling to fathom the loss. Bates College published a special tribute, calling Russ’s death a sad day for Panthers and for Bobcats. An appreciation was prepared for the football’s printed game program by sports journalist Andy Gardiner. Erin Quinn ’86, Russ’s successor as AD, was quoted in it: “A lot of people in athletics are defined by a particular thing. Bill Beaney was the hockey coach. Mickey Heinecken was the football coach. But in a really important and heartwarming way, Russ was more defined by being Russ Reilly.”

In September, in a nearly full Mead Memorial Chapel, on a glorious last-day-of-summer afternoon, colleagues, former players, friends, and community members gathered to celebrate Russ’s life. The AD from Connecticut College was there. The Tufts coach was there. The former UVM coach. The former Dartmouth coach. Dave Hixon, the head coach of the school Russ loved to hate, Amherst, was there. And scores of very tall young men.

Middlebury president Laurie Patton announced that Ted Virtue ’82, one of Russ’s captains, had endowed a new chair in the athletics department: the Russell L. Reilly Basketball Coaching Chair. Missy Foote spoke. Russ’s daughter Jody spoke. She talked of growing up with that oversized voice echoing around town on Saturday afternoons. How her friends who had attended her father’s basketball camps still felt a rush of fear when someone yelled, STANCE!

Playing away at Bates, Middlebury’s football team won 28–0. Youngman Field was quiet.

At the reception in Pepin Gymnasium following the service, impromptu reunions broke out and stories flowed.

“It was hard to keep reminding myself that this was a somber event,” Lindholm said.

Russ Reilly had given voice to Middlebury’s deepest values. As a result, generations of Middlebury students had found their own voices. Hundreds had come here to pay their respects. To show their respect.

Guinness was served.

Leave a Reply