By the time Will Bellaimey ’10.5 was in fourth grade, he already had two copies of the Scholastic Encyclopedia of the Presidents and Their Times. One had stiff, square pages; it was his prime, stay-at-home copy. The other was his beater. The cover was warped, edges tattered, every single page wrinkly from being dropped in the bathtub—because he read it in the bathtub. Bellaimey had the tremendous force of a fourth-grade boy’s interest, yet while other classmates learned every notch of a stegosaurus or pored over Ken Griffey Jr.’s baseball stats, Bellaimey focused his attention on the U.S. presidents. Every single one of them. And he was obsessive. When an opportunity arose for a class project: U.S. presidents. When talking to an adult: the presidents. Lunch table conversations: ibid. His friends, well, they humored him. They would hit pause on their own ramblings about when a triceratops was first discovered during the “Bone Wars” to allow for Bellaimey’s monologue on how William Henry Harrison eschewed an overcoat and rolled up his sleeves on a cold and rainy Inauguration Day—and died of pneumonia a month later.

But as his peers moved on from dinos, the presidents never left Bellaimey; or, he never left them. Middle school, high school, college. Presidents, presidents, presidents. This facet of American history was part of the reason he decided to study political science. He thought he’d join his idols one day. He thought he’d be president.

So when, even years after Middlebury, a friend asked, “Can you tell me the history of the United States?” he was prepared, with a caveat: “I can tell you the history of the presidents.”

But he may not have been prepared for her response.

“OK, great. When?”

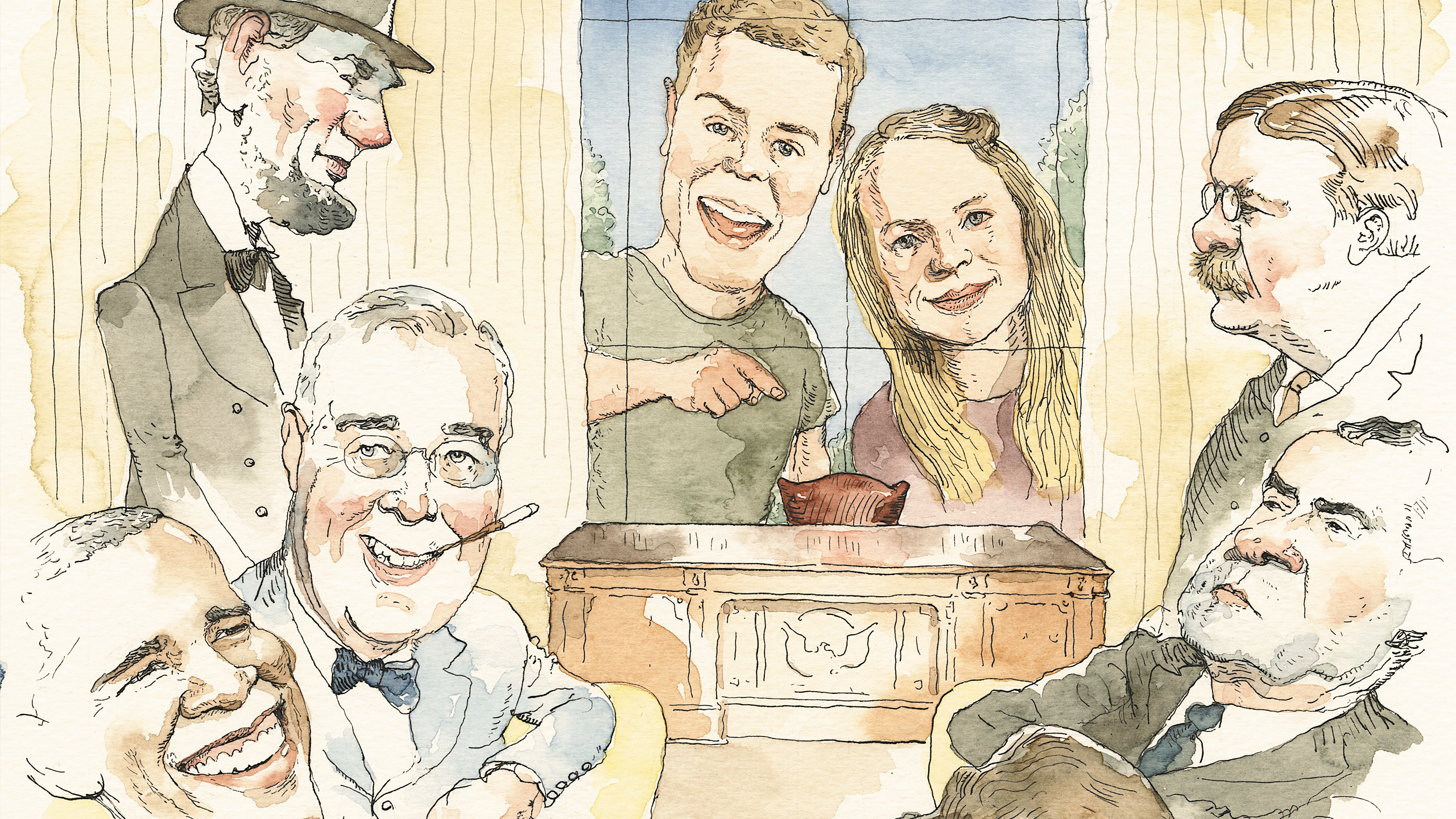

Will Bellaimey and Bianca Giaever ’12.5 don’t exactly recall when they first met. There is a distinct memory of one encountering the other in costume on top of Chipman Hill, but, no, that doesn’t make sense; they’d already known each other when all that happened. It could have been that one was dating a friend of the other’s, or maybe it was just they’d met outside a party, or heard about another cool Feb. No matter. What is easy to remember is just how well they hit it off, how quickly the two imaginative brains were working together, creating recklessly.

Giaever had that same curious drive, the need to know. But like most everyone else, she aimed it at something other than the U.S. presidents. For Giaever, it was stories. She’d long been asking questions, seeking advice, talking to strangers, and when a journalism teacher in high school encouraged her, she found she could make something out of that curiosity. She spent an entire year working on a feature story for her high school magazine, interviewing, spending time with, and getting to know a classmate with terminal cancer. Eventually, the story would land on the cover of Seattle Weekly. She was 17, but the possibilities cracked open. Writing, radio storytelling, video. There was a whole world out there, and so many ways to tell its stories.

When the two met, they immediately started “creating ideas,” Giaever says. There was a scavenger hunt on the Trail Around Middlebury. There was the time they enticed a bunch of strangers to have dinner together, an event that evolved into regularly scheduled gatherings involving strangers, well, having dinner together.

And then there was that not-to-be-named storytelling event, the one inspired by a national organization, the one that produced large crowds and a “please don’t use our name” cease-and-desist letter from the organization itself. But even when they weren’t staging events that most everyone on campus was talking about, they were conducting their own personal salons, their tenacious curiosity leading one to spill all they knew about any given subject while the other soaked it all in.

And then they went their own ways—graduation, life, jobs. Bellaimey set aside his presidential ambitions and went into teaching; Giaever produced a senior video project, the Scared is scared, that went viral and captured America’s heart and attention. She began to tell stories for a living, earning Emmys and acquiring a talent agent.

Of course, they remained great friends and saw each other frequently; they just didn’t have the time to collaborate on big projects like they used to. Until one day, they did.

It turns out that Bianca Giaever proved to be the perfect, imperfect partner to Bellaimey’s presidential obsession. In college—or shortly thereafter—she had come to grips with her lack of knowledge of U.S. history; while she had been focusing on discovering and sharing stories, the one about the U.S. never quite stuck. Which is how she came to ask Bellaimey to offer his take, and he said he’d tell her about the presidents instead.

It was early 2017, and Giaever and Bellaimey sat in Bellaimey’s apartment, knee to knee in the Harlem studio, bed in the corner, kitchen in back, a few cans of La Croix between them. Giaever’s microphone was there, too—“Bianca uses her microphone as an excuse to have conversations she wants to have,” says Bellaimey—and in this case Giaever wanted a deep dive into the American presidency. She’d been working at the New York Times podcast The Daily, and with more coverage than almost ever before focusing on the presidency, she wanted the expertise of her friend. She wanted the context, the history, those unseen connections, parallels, and repetitions.

“I had gone to see Will teach before for fun, and I really admired his teaching style. I wished I could take his class,” says Giaever. Bellaimey was the history teacher Giaever never had, she says. He doesn’t stand at the front of a room and lecture. He moves, engages, tells stories. He involves everyone, she adds.

Afterward, she kept thinking, Wouldn’t it be great if more people could experience that? So when Giaever wanted to know more about the presidents, she brought her mic so that others could listen in.

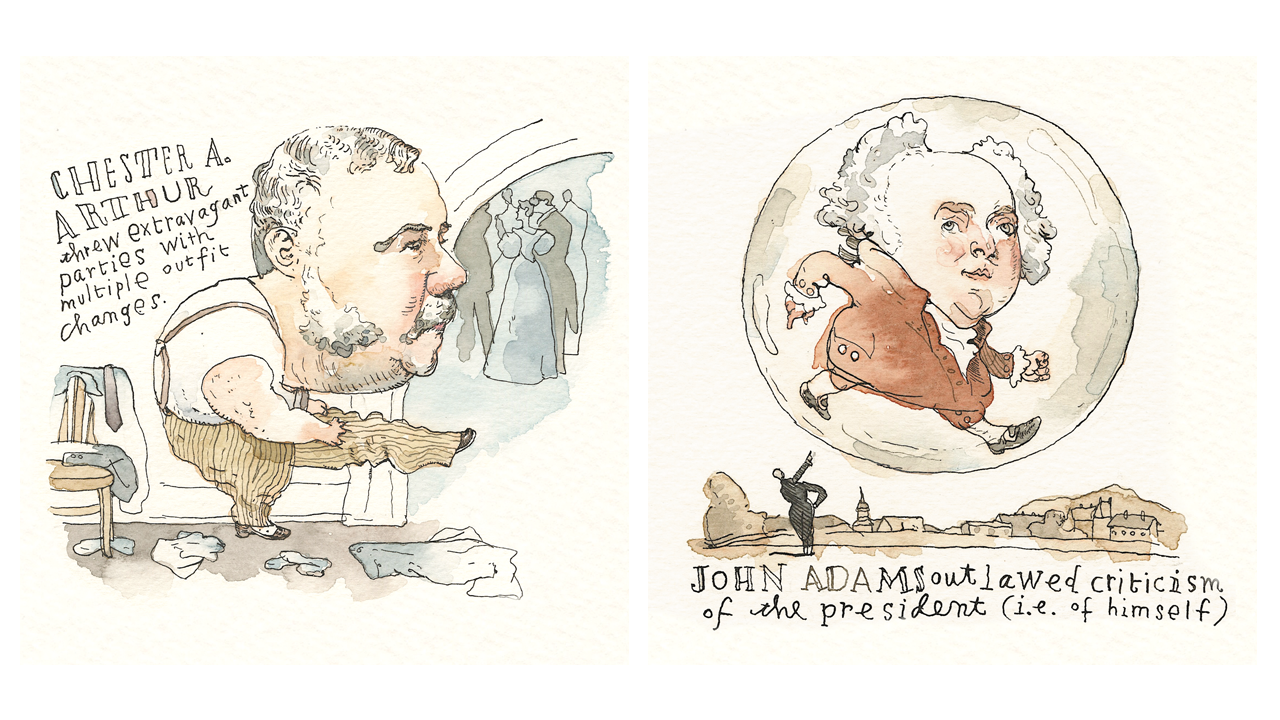

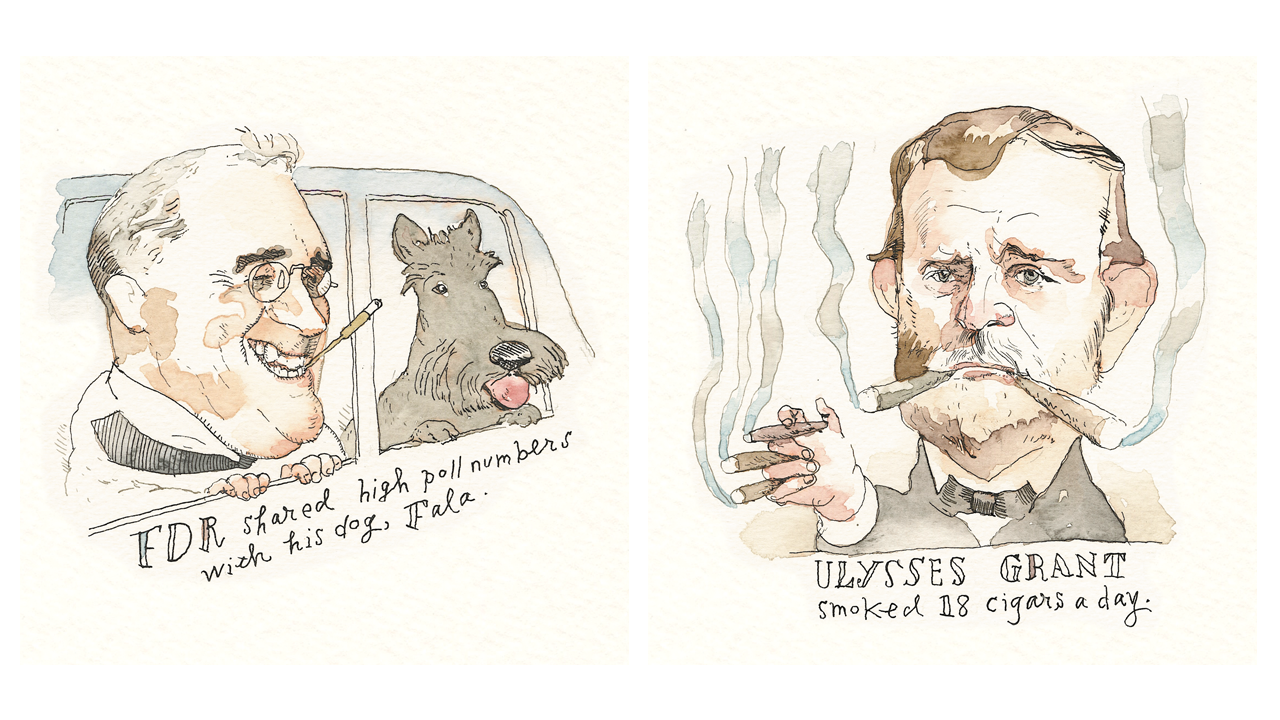

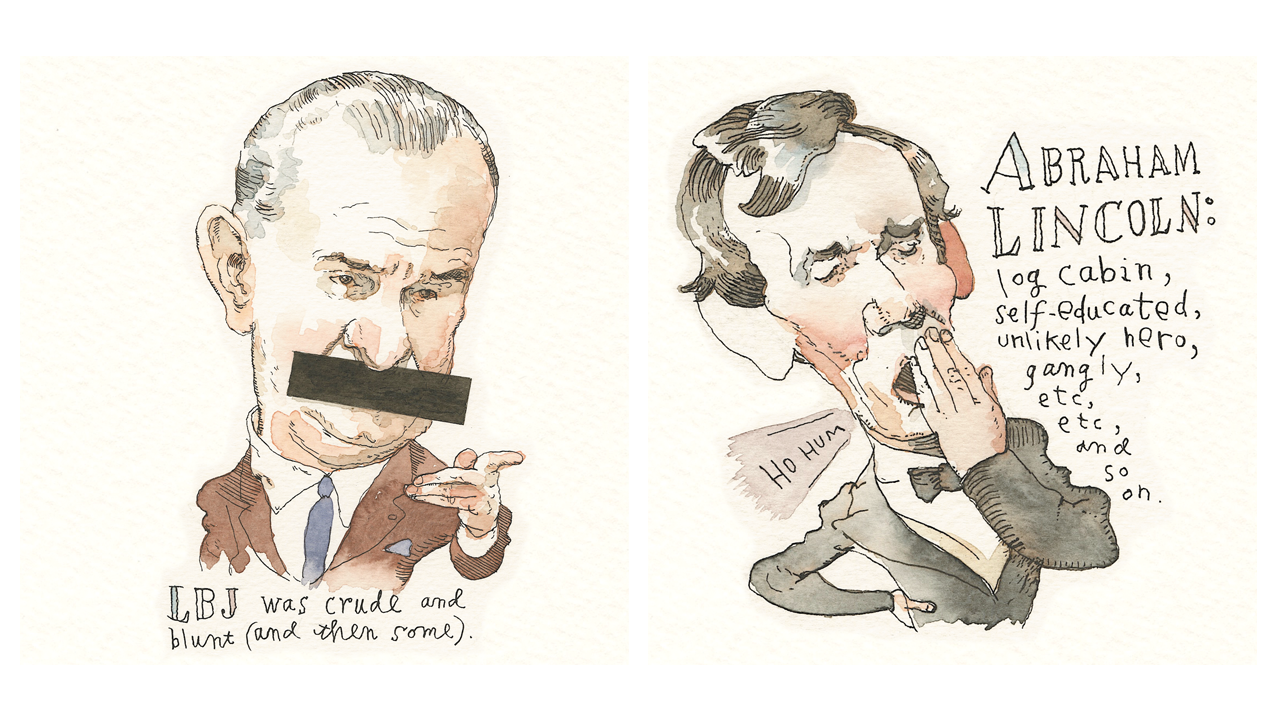

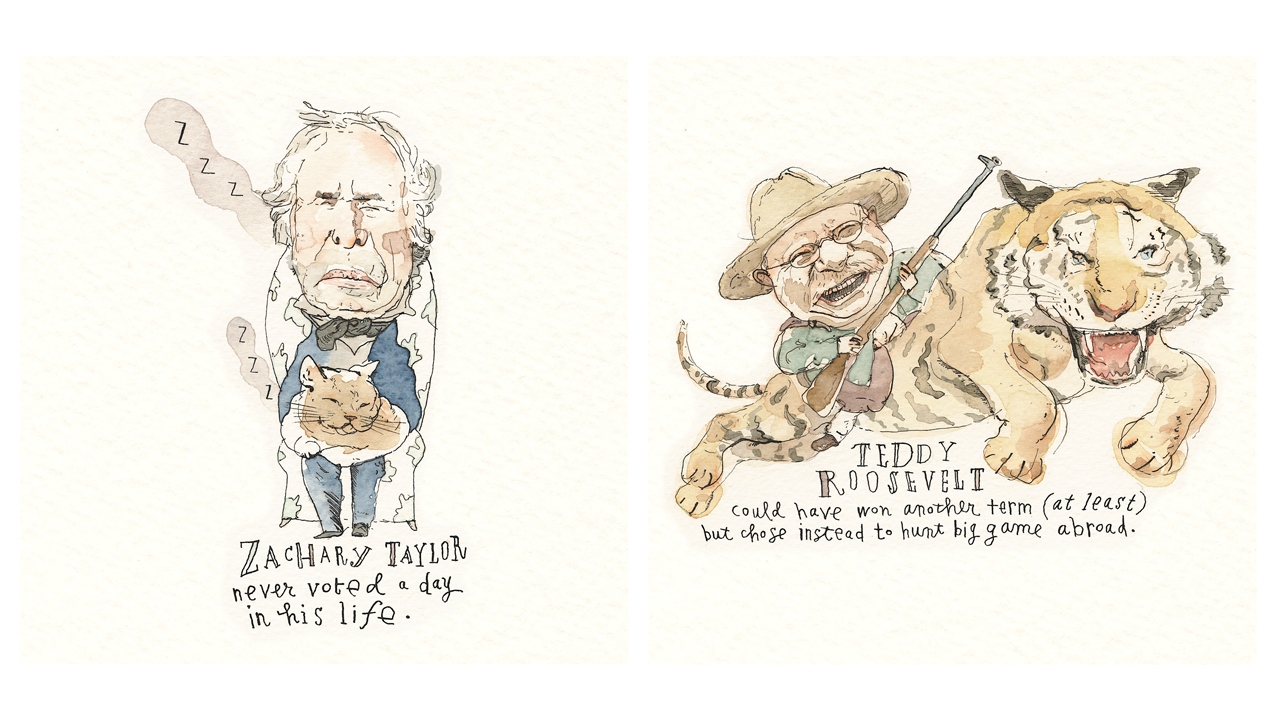

“Tell me about George Washington”—and off Bellaimey went. It was as if his thoughts were artesian—information naturally springing forth, effortlessly. Nixon avoided accusations of corruption (temporarily, at least) by giving a speech about his dog, Chester Arthur was a clothes horse who would change outfits multiple times during the same party, James Buchanan was likely our first gay president. Bellaimey was excited and excitable, pausing to think, to get the details right, before rushing through the back end of a story, his voice rising into a shout, then dropping, his tone changing to do a different character. He didn’t use notes; everything Bellaimey said sprang from memory.

In that moment in that studio apartment, the history of the United States became a novel with 45 main characters. (Obviously the presidency isn’t the entire history of the nation, but it’s “a chance to get into everyone’s brain,” he says.)

The first day they went all the way from Washington to Lincoln. One after another. In order. It took hours, and both emerged a bit shell-shocked. A few weeks later they convened again, this time advancing from Andrew Johnson to FDR. And a few weeks after that—they both needed a presidential detox in the interim—Truman to Trump. They went straight through in chronological order. They couldn’t do it any other way. If you did, says Bellaimey, it’d be “like picking up Harry Potter at the end of the thing. You can’t do that.” You’d miss the themes, the story line, the arc of history that includes 45 presidents over more than 200 years.

When Bellaimey finished talking, Giaever had more than 11 hours of material.

“I never thought the tapes would go beyond the apartment,” Bellaimey says. Not that he mistrusted Giaever; he just figured life would get in the way, and what could she do with 11 hours of material?

Well, cut it to eight and divide the eight hours into 45 chapters, one for each president. And even with three hours on the cutting-room floor, what you hear is almost exactly how the conversation proceeded. “I wasn’t doing much narrative framing,” Giaever says. “Will had already done that in his head. I was sprucing and trimming that.”

The resulting podcast, All the Presidents, Man, can be listened to episodically (chapters run between five and 12 minutes), but you’re going to want to binge many at a time.

The story of American presidents—Bellaimey’s story of American presidents—is one that will have you standing with an unfolded shirt above your laundry basket for five minutes as you learn that the colossally prickly but short Martin Van Buren had the nickname “Old Kinderhook,” which he’d shorten in a signature to OK, purportedly leading to our modern term of approval. Or that James K. Polk had the campaign slogan “Fifty-Four Forty or Fight,” which is one of the most intense statements I’ve ever heard about latitude, or that Chester Arthur could write in Latin and Greek, simultaneously, with a pen in each hand. It’s a story that leads you to stare blankly into the middle distance, uttering, “That’s weird,” while wrinkles set into the chinos you haven’t even dug out of the bottom of the laundry basket yet.

The podcast is escapist, sure, but not in a mindless way. In fact, it could be seen as an antidote to our times. It taps into our need, our drive, our hunger for presidential politics, but without the life-or-death consequences of the present. We know what the outcome is—we are living it—which makes the gambles, laws, corruption, and oddities palatable rather than overwhelming and all-consuming. We are given enough space from the presidents to think about them, analyze them, be entertained by them. It’s a space that network news can’t provide. Bellaimey’s reverence for the office and those who have held it is obvious, but he wrestles with the fallibility of the men. He loves George Washington but doesn’t ignore the fact he had the option to free his slaves, but didn’t. Or that Thomas Jefferson enslaved his own son. Or that the Republicans traded the end of Reconstruction for the election of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Over the course of eight hours, we are able to see the recurring themes and drives of the American political machine and those who have helmed it.

For many months, Bellaimey was right: the podcast didn’t go anywhere, save for a file he emailed to his mom and a replaying of the George Washington episode during one of Giaever’s road trips. But

reality—current events, the presidency, all the mess that has renewed public interest in presidential history and politics—seemed to demand a bigger audience for the project.

“Things we are struggling with today have their own echoes in things we were struggling with in the past,” says Bellaimey. “Things that we are really fighting hard for now are things they’ve been fighting for since the beginning.” And that’s something worth holding onto. Celebrating, even.

When all else is unsure, the curiosity born of a precocious fourth grader and the quality of a story well told is all one can ask for.

All the Presidents, Man can be found at Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pocket Casts, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Leave a Reply