When Dr. John “Bull” Durham ’80 met Woodjina in a stifling, crowded ward of Port-au-Prince’s La Paix Hospital, the five-year-old girl was dying. For weeks, she’d been confined to a dirty mattress, unable to walk, beset by a spiking fever and festering bedsores. Her left hip was badly dislocated, her lower leg wrapped in a cardboard box. Fixed to the end was a crude traction device, a Coke bottle filled with murky water that dangled by a string from the edge of her cot. Her right leg was wrapped in a homemade splint.

Woodjina’s case was as confusing as it was concerning. An X-ray of her right femur was unlike anything that Bull, an accomplished orthopedic surgeon, had ever seen—perhaps a tumor, perhaps a rare, spontaneous infection. He couldn’t be sure. Her left hip, meanwhile, appeared to be dislocated. “It was just bizarre,” he recalled.

In the U.S., such a condition would have been caught quickly and treated easily; even without insurance, an American can walk into any emergency room in the country and receive world-class care. Woodjina’s family lived in Haiti’s rural Central Plateau, where health care is virtually nonexistent. She had been limping and feverish for three months before she was brought to a hospital in the capital. Her family’s inability to pay for antibiotics could easily have been fatal.

As he often does while working in Haiti, Bull snapped photos of the X-ray films and emailed them to a colleague back home. It happened that the colleague was at a surgical conference in Miami, having dinner with the world’s foremost expert in pediatric orthopedic infections. The surgeons handed the phone around the table, swapping ideas and diagnoses. Within hours, Bull had the consult he needed. Woodjina’s hip surgery would require an anterior, or front, approach—something Bull, a hand specialist, had only performed once before. He called another colleague, a lower-limb specialist in Flagstaff, Arizona, who talked him through the procedure, step by step.

The operation got under way late in the day, with Bull scrubbed in alongside a team of Haitian surgeons and residents. Their fears were soon confirmed. The head of Woodjina’s left femur was necrotic, dead, and would have to be removed entirely. She would never walk normally again. From her right femur the doctors drained a half liter of pus, then scraped away dead tissue and packed the infected bone with antibiotic-infused beads—a treatment nearly impossible to find in Haiti, but which Bull had brought from his clinic back in the States.

“It’s a rare opportunity, as an orthopedic surgeon, to save a life,” he said. “That doesn’t happen very often.”

Within days, Woodjina had left the hospital, returning home to the Central Plateau, and Bull had left the country, returning home to northern Arizona. For a week or two, he received updates on her recovery. Then, silence. He began to wonder if she’d survived after all. A recurrence of her infection could have quickly gone septic, poisoning her bloodstream.

Six months later, Bull was back in Port-au-Prince. He had just finished rounding on patients when a familiar young girl came streaking across the hospital’s sunny courtyard and leaped into his arms.

The doctor wept.

John Durham, “Dr. Bull” to his colleagues and patients alike, first came to Haiti in 2010, just weeks after the 7.0-magnitude earthquake hit that leveled Port-au-Prince, claimed 280,000 lives, and left 1.5 million homeless—one of the worst humanitarian disasters in history. He has since returned to the country more than 30 times. Long after international aid groups have packed up their tents and gone in search of the next crisis, Bull remains transfixed by a singular mission: helping Haiti rebuild its healthcare system, one surgeon at a time.

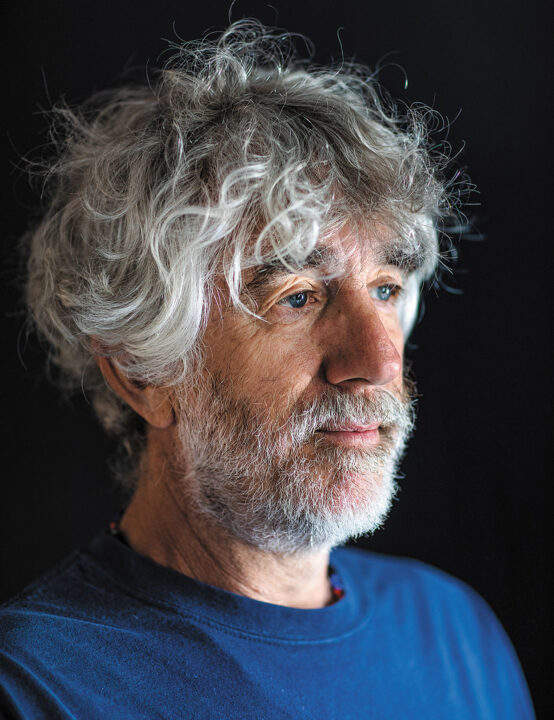

Bull is 60, a fact he finds hard to believe. He’s lean and tan, with strong, confident hands and woolly eyebrows that seem forever raised, above his bifocals, in amusement or wonder. He wears his hair, gone white, long and shaggy, hiding a turquoise ear stud, as if the ’70s never ended. His fashion sense tends toward Waldorf School Dad: fanny pack, beaded African necklace, colorful socks and sandals. With his salt-and-pepper beard, inquiring eyes, and a mischievous smile, he looks like a skinny Jerry Garcia.

Bull was 20 years into his surgical career and a partner at a thriving orthopedic practice in Flagstaff when, overnight, the Haiti earthquake upended millions of lives—including his own. He recalls his first trip to the country, made in the month after the disaster: descending over a blacked-out Port-au-Prince, unloading the plane’s cargo hold by headlamp. The airport tarmac had been converted into a 300-bed trauma field hospital, where critically injured patients were being triaged and treated under enormous tents. Overseeing the operation was Project Medishare, an American nonprofit founded in 1994 by two doctors from the University of Miami who had extensive experience in Haiti.

Bull found himself assigned to three nonsterile operating theaters, alongside nine other orthopedic surgeons; he quickly realized what the effort needed more than anything was a logistics coordinator. “There are a lot of talented doctors and providers in Haiti,” he said, “but no one knew where they were.”

More than 50 hospitals and clinics around Port-au-Prince had been destroyed in the quake. Bull spent two days calling every number he could find, compiling a list of more than 200 physicians around the country who were accepting patients. When he returned to Flagstaff, he left the list behind.

On his second trip to Haiti, acting as chief medical officer, Bull worked with a pediatric intensive care team, treating children with grievous injuries. “On the day I arrived, there were nine kids in the beds,” he said. “By the end of the week, all those kids were dead, and nine new kids had replaced them.” Many of the volunteers from those early trips have not returned to Haiti since, which Bull chalks up to traumatic stress from the experience. “In the United States, we just never see things like that.”

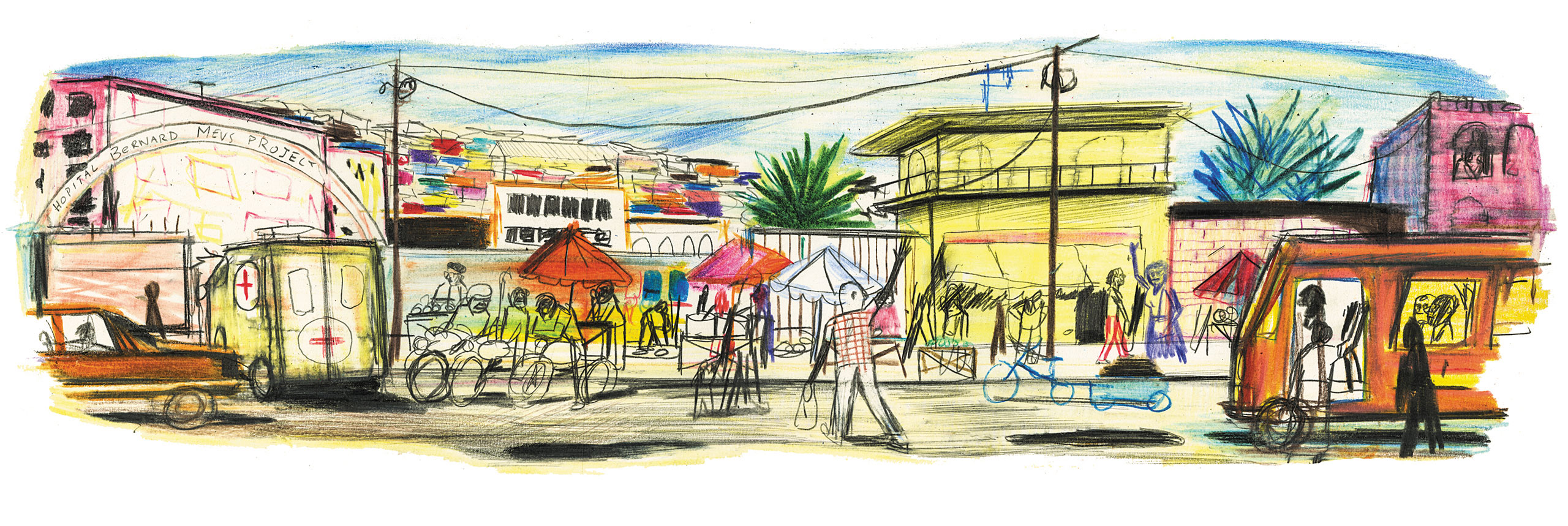

By the summer of 2010, Project Medishare had begun to wind down operations at the field hospital, transferring patients and equipment to Bernard Mevs, a private, 50-bed hospital in the city center, owned and operated by twin Haitian surgeons. Like nearly all buildings in Port-au-Prince, Bernard Mevs had been badly damaged in the earthquake. Project Medishare invested heavily in its restoration, with the aim of transforming it into Haiti’s premier trauma center. Nine years later, it is one of the only critical-care hospitals in a country of 11 million people. Bull has now spent so much time at Bernard Mevs that he is beginning to know the nurses, attendings, and residents as well as those back in Flagstaff. “It feels like coming home,” he said.

Bull’s first home, his childhood one, was in Monson, Maine, a town of 800, where his grandfather owned a furniture factory. His father, a Middlebury graduate, helped run the family business, and his mother, a nurse by training, raised Bull and his two younger sisters. From a young age, Bull was enamored of the small town’s family doctor, a fellow named Lightbody who lived out in the country, made house calls, and would always stay for dinner. Bull dreamed of one day carrying a leather doctor’s bag himself.

He was a talented student and dutiful son, more interested in washing the dishes to get the car keys than smoking dope or playing the truant. Summers he spent with his mother and sisters in a cottage down east, near Belfast, where he ran a small lobster fishing business. He built his own traps, knit his own heads and bait bags, and fished the bay in a small rowboat, a gift from his grandfather, plying his catch to the summer crowd.

Skiing, though, was his first great love. He came of age as the freestyle scene was taking off—the days of

“Airborne” Eddie Ferguson and films like The Good, the Rad, and the Gnarly. In high school, Bull competed in ski ballet, twirling down the slope and flipping over his poles in a flowing white satin costume while John Denver’s “Windsong” played over the PA.

He arrived at Middlebury in 1976. He was assigned a room in the basement of Stewart Hall, affectionately known as “the Pits,” where he quickly formed a tight-knit circle of friends. “Bull was always hitting the books harder than anyone else,” Billy Erdman ’80, who lived down the hall from him in the Pits, said. The two spent late nights studying for chemistry exams and mooning over their latest campus crushes. “We were a studious group, but we had a mischievous side.” Erdman recalls fashioning tennis ball cannons from soda cans and duct tape, and launching blocks of sodium from the roof of the science building with a slingshot, producing sensational fireworks in the puddles below. “Bull has never been short on energy,” Erdman said. “He was always the instigator of the group.” Days after graduation, Bull and his classmate Dave Halsey ’80 rigged up Bull’s beloved red Jeep with two jerry cans of gas, two spare tires, and a chainsaw; loaded the rear chuck wagon with food; and hit the road for Alaska. He was to start medical school at the University of Vermont in the fall, but first he wanted to taste life on the frontier. He got a job on a salmon boat out of Yakutat for the summer; for a kid who grew up on the water, it was a dream come true. In July, he called UVM and asked to defer for a year.

“They told me I’d need to reapply. I said, ‘Send me an application.’”

“Bull has never been short on energy,” Erdman said. “He was always the instigator of the group.”

As if in a Jack London novel, Bull crewed the boat down to Seattle at the season’s end and found work in a crab-packing plant for two months, throwing around hundred-pound boxes of fish. As the cold arrived, he made his way back to Alaska and Turnagain Arm, where, for 10 bucks, the Forest Service gave him 20 acres of land to clear-cut for firewood. He worked the lifts at Alyeska Resort and skied enough days to make up for the four lousy winters he’d had at Middlebury. “My only regret is that I didn’t do it for another year,” he said.

Even once he got to UVM, his trajectory was anything but linear. “I didn’t know what an orthopedic surgeon was when I started med school,” he said. In his third year, he did a two-week ortho rotation and hated it. “All the docs were assholes, and I couldn’t wait for it to be over.”

The last day of the rotation was a particularly miserable one. His dad had just died of a sudden heart attack, and he was living with a friend in an unheated cabin outside Burlington. “I was depressed, and I couldn’t face going home and having to start a fire. It was a Friday night, and I called the chief resident and told him, ‘I’m taking call tonight.’”

The resident, confused as to why Bull would volunteer for an extra shift, nevertheless assigned him two chapters of reading on internal fixation and told him to come to the ER when he was finished. “That night, as a third-year med student, I put a plate on a tibia fracture, which is unheard of. I walked out of that surgery and said, ‘Holy fuck. This is what I was meant to do.’”

In his third year, against the counsel of the department chair, Bull took six months off from school to volunteer in the south of India with the Nilgiris Adivasi Welfare Association. There, he worked in a small rural hospital, providing care to the region’s indigenous tribal population. “We’re talking grass huts, tigers, and rogue elephants that would destroy entire villages,” he says. “It was exotic.” It was his first taste of medical mission work, and it sure beat sitting in Vermont, churning out research papers.

When Bull returned to the States, he sought out Sigvard Hansen, the father of modern traumatology, who ran the orthopedic program at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle. He spent the next six months working alongside Hansen before returning to UVM to finish his degree. True to form, graduation day found him not in a cap and gown, walking alongside his peers, but back in Alaska, windbound in a snow cave at 12,000 feet on Mount St. Elias, the second-highest peak in United States. Three weeks of foul weather shut down his summit bid, but he wouldn’t have had it any other way.

While in Seattle, Bull had met a clinical social worker named Lisa Jobin, a redhead with a disarming smile who worked for Child Protective Services. When he matched to a residency program in Albany, New York, she moved east and became a maternal HIV counselor in the hospital where he was training. Bull and Lisa wed in 1987. By the time they moved to Iowa City, where Bull had accepted an upper-extremity fellowship, she was pregnant with twins. Following the fellowship, the couple settled in Flagstaff, where he joined a fast-growing orthopedic practice and she took on the full-time job of raising their young sons.

In the late ’90s, Bull got involved with the Northern Arizona Volunteer Medical Corps (NAVMC), which organized international mission trips for local doctors and nurses to far-flung destinations, including Mexico and Brazil. The group often took a siege approach to their missions: an advance team would host a clinic, see a hundred patients, and select 40 for surgery. The docs would parachute in and do as many procedures as they could in a week. “Then we’d go home and hope someone followed up on them. As time went on, I became interested in what we could do to make our work sustainable—to do more teaching.”

He began organizing trips to a trauma hospital in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, using a different approach. “We were teaching residents, working alongside them, developing relationships. I thought, ‘This is it. This is what I’m going to do—once a year, I’ll come over here.’ I was planning the 2010 trip when the earthquake struck Haiti. Thirty-two trips later, here I am.”

The streets of Port-au-Prince are a riot of color, an intoxication of scent, a cacophony of sound. Smoke settles heavily over the city—diesel fumes, charcoal grills, wood stoves, burning tires. The crush of traffic between the airport and Hospital Bernard Mevs obeys no laws or street signals, but ebbs and flows with a kind of contained chaotic precision. Jacuzzi-size potholes dot the roadways, and drivers freely use the sidewalk as a third lane.

Everything is for sale—bras and blouses, eggs and oranges, cell phones and cigarettes, griot (fried pork) and pikliz (spicy cabbage), liquor and lotto tickets. The hills are awash in color, with cinder block homes painted pink and canary, robin’s egg and sea foam, like a pastel Modigliani as far as the eye can see. At the filling stations, moto-taxi drivers slouch on their bikes, swapping gossip and waiting for fares.

Haiti has long been one of the poorest countries on earth. According to the UN, one quarter of Haitians survive on less than $1.25 per day, and youth unemployment hovers around 40 percent. Less than half the population is literate, and just a third will attend high school. The infant mortality rate is 10 times higher than in the United States. Annual healthcare spending is 46 dollars per person.

As Bull often reminds new volunteers, “The United States has not been a friend to Haiti.” For the first 60 years of the country’s independence, the U.S. refused to recognize the new “Black Republic.” In 1915, U.S. Marines invaded the country, oversaw the creation of a new constitution favorable to American corporate interests, and occupied Port-au-Prince for nearly 20 years.

In the ’70s, fears that a swine fever epidemic might hurt the American pork industry led to the nationwide slaughter of the Haiti’s native Creole pigs; USAID replaced the animals with American pigs poorly suited to a Caribbean climate, few of which survived. In the ’80s, the Reagan administration flooded the country with cheap American rice, feeding hungry families but crippling Haiti’s domestic rice industry.

In 2010, following the earthquake, the Red Cross raised $500 million in donations, but an investigation by NPR and ProPublica later revealed that, with that money, the organization built just eight permanent houses. Since the disaster, a devastating cholera epidemic has killed some 10,000 Haitians and sickened more than a million; the outbreak was quickly traced back to a UN peacekeeping base, which was spilling human sewage into the Artibonite River, one of the country’s main water sources.

Haiti is the only nation in history born of a successful slave revolt, and it can seem, at times, as though the country is still paying the price.

In early December 2018, Bull brought a team of 16 surgeons, nurses, and techs from Flagstaff to Bernard Mevs. For weeks this past winter, violent demonstrations roiled Port-au-Prince, stemming from corruption charges against the president. Street battles between antigovernment protesters and national police left at least eight people dead, including an officer who was reportedly burned alive. Schools and businesses were closed, and two days before the group arrived, the State Department evacuated all nonemergency personnel. “Haiti is always in crisis, but this crisis is the worst I’ve seen,” a moto-taxi driver told the Associated Press. Bull knew this was not necessarily everyone’s idea of a vacation. “It can get pretty fucking intense down here,” he said.

Each member of the team arrived carrying two 50-pound duffel bags. Inside were the contents of a mobile operating room, from gloves, gauze, and shoe covers to plates, screws, and titanium rods. Organizing and inventorying the 1,700 pounds of supplies took half a day, by the end of which Bull was beat but beaming.

In the morning, the team hosted an open clinic. The hospital’s staff had spread word in advance of the team’s arrival, and patients had traveled from across the region in hopes of being seen. In the States, orthopedic surgery tends toward sub-specialization; when he was in private practice, Bull operated almost exclusively on hand patients. In Haiti, he’s never sure what might walk through the door next.

In clinic, the surgeons evaluated an aging woman, frail and stooped, whose mandible was missing, lost to cancer; in its place was an exposed metal plate, which she hoped could be replaced with something more permanent. A young man hobbled in on crutches with open, weeping wounds on his hip and ankle; X-rays revealed that tumors had destroyed both joints. A woman who’d been attacked and raped in Cité Soleil, leaving her with keloid scars on her neck, wanted to know if the disfiguring tissue could be removed. A young man in a wheelchair—an ex-gang member and father of two, whose wife was killed in Hurricane Matthew—with gaping pelvic pressure sores was told that closing the wounds only risked deadly infection. A four-year-old boy, whose foot had been so badly burned as an infant that the appendage was now barely recognizable, came in with his mother; the doctors discussed amputation before deciding that his best hope was to see a prosthetist. A 30-something woman with exposed tendons at the site of her wrist fracture was scheduled for surgery both to repair the break and graft new skin. A car accident victim in a plaster ankle cast was deemed operable, as was a grandmother with a broken hip. “When we’re done,” Bull promised her, “you’ll go dancing.”

Bull no longer goes to Haiti primarily to perform surgery, but to spend time with the next generation of Haitian orthopedists. He realized, early on, that education would be his force multiplier—that his ability to create enduring change had less to do with his skill as a practitioner than with his passion as teacher. Importing American surgeons to operate on Haitian patients was not a sustainable form of development. He needed to make himself irrelevant. “The only way it makes long-term sense is to teach,” he said. “That’s ultimately what we need to be doing down here: changing our role to that of consultants. Education is so key.”

When he is at Bernard Mevs, residents and attendings flock to the hospital, often after putting in a full day elsewhere. Scrubbing in with him is their chance to work on particularly complex cases and take advantage of the specialized orthopedic hardware and implants he brings from Flagstaff. Bull supervises these surgeries, but the scalpels and retractors stay firmly in the residents’ hands. Likewise, the American anesthesiologists on his team work with their young Haitian counterparts to guide them through sophisticated conscious sedation techniques, such as ultrasound-guided nerve blocks.

The day after the clinic at Bernard Mevs, as surgeries got under way, he caught a ride across town to La Paix Hospital, where he tracked down a group of residents and rounded on the orthopedic ward with them. When he’s teaching, Bull eschews the didactic in favor of the practical. He has little interest in lecturing his students about various grades and classifications of fracture. “I want to teach them things that will be of use to them in the OR,” he said.

The group wended its way through the ward, pausing along the way to examine injuries, take histories, read X-rays, and discuss surgical interventions. Through a translator, he pressed the young docs on diagnoses and tactics. A few of the patients were deemed candidates for surgery back at Bernard Mevs, and they began a pre-op workup with the anesthesiologist. Many more were not.

Bull likens these trips to the city’s public hospitals to a toy-picker machine—random and cosmically unfair. He often tells the story of walking into the ortho ward at Port-au-Prince’s General Hospital a few years ago to find eight patients with 10 femur fractures between them. In the first bed was a young man who’d arrived with both legs broken, but who only had the money to repair one; he’d chosen his right.

Bull and the residents will do what they’re able, with the supplies they have, in the days they can. It is never enough. He can’t say why he keeps returning to Haiti. He doesn’t think of it as altruism, nor born from a sense of guilt or obligation. He’s not one to play savior or post poverty porn on his Facebook feed.

“I know doctors who would say, without a moment’s hesitation, that their work down here is a calling,” he says. “I envy that to some degree. That would make it easier for me, to know I was called to do it. I just really fucking like it.”

When he was in private practice, the trips to Bernard Mevs couldn’t come often enough. “I’d get to the end of my rope about shit in my office, and I’d come down here for a week and it’s like, holy fuck—it puts your life in perspective.” (Last year, he officially retired from his orthopedic group and began operating three days per week in Tuba City, Arizona, on the Navajo Nation—an arrangement that itself resembles international aid work.)

Bull’s friends have their own theories about his urge to serve. “What’s interesting about Bull is his constant curiosity and interest in people from other walks of life,” Frank Sesno ’77 said. “Here’s a kid from small-town Maine, reaching beyond his comfort zone from the very beginning. Whether it’s India or Haiti, his curiosity about people and places exceeds his boundaries. That’s just Bull. He wants to experience the world in almost a literal sense.”

Billy Erdman put it even more succinctly: “His heart is as big as his brain.”

The bone was in multiple pieces—on the X-ray, the fragments appeared to float in space—and without an operation, the young man’s arm would be crippled for life.

In recent years, Bull’s focus on education has carried him far beyond the hospital itself. Since 2010, NAVMC has been funding work at Renmen orphanage, an hour outside Port-au-Prince, where volunteers from Flagstaff have rebuilt a security wall, installed a generator, hired a primary school teacher, and rewired the building. After a 10-year-old boy died of tetanus—an almost unheard-of occurrence in the States—the group brought enough vaccine on its next trip to inoculate all 55 children.

Each December, Bull and Lisa rent buses and take the entire orphanage to the beach for a day; for many kids, it’s their first time seeing the ocean. Bull is most proud, though, of the educations NAVMC has funded; in addition to sending every student to high school, the nonprofit has sponsored students pursuing degrees in nursing, law, plumbing, hotel management, and, naturally, medicine.

One day in 2011, while Bull was working at Bernard Mevs, Lisa arrived from the orphanage carrying a small girl in her arms, a suggestion in her eyes. Anabelle had been left on the steps of a local hospital on the verge of death, malnourished and sick with typhoid. Nurses spent five months caring for her before bringing her to Renmen. At two-and-a-half years old, she could neither walk nor talk.

Bull and Lisa had been empty nesters for just a few months—the twins were finally off to college—and Bull was looking forward to spending more time skiing and kiteboarding, guilt free.

“My immediate reaction was, ‘Let’s go home and get a dog,’” he recalled. “We decided to give it thought for a month.”

Two weeks later, Lisa told him she didn’t see changing her mind. The adoption process took two years, during which time the couple flew to Haiti every few months to spend time at Renmen. Today, Anabelle is nine—a tropical storm of curiosity, a precocious scientist, and an aspiring ballerina.

Reprising the role of Parent of a Young Child has seemed to invigorate Bull, who once again spends his weekends working on science projects and attending dance recitals.

Of all the hats he wears—surgeon, teacher, husband, volunteer coordinator—dad might be the one he delights in the most.

One night in Haiti, while the rest of the team was scrambling to stabilize a cop who’d been brought into the emergency room, barely conscious, with a bone-deep machete wound to the back of his neck, Bull was in surgery with two Haitian attendings and a resident, reconstructing the shattered elbow of a patient they’d met at General Hospital. The bone was in multiple pieces—on the X-ray, the fragments appeared to float in space—and without an operation, the young man’s arm would be crippled for life.

The operating rooms at Bernard Mevs were cool, blue, and bright, like standing at the bottom of a freshly painted swimming pool. The floors and instrument carts gleamed under the powerful lamps overhead. Bull’s stainless steel tools were laid out like a fine dining set, freshly unwrapped from their sterile packaging: clamps, saws, drills, scalpels, forceps, mallet. Beside them was a colorful set of implants: plates, screws, and wires. Four types of suture. A kick bucket for bloody towels. A long-wristed pair of surgical gloves, size nine. A small speaker for reggae and Jimmy Buffett.

Before the operation started, the team paused for a time-out: right patient, right site, right procedure. Tourniquet on. Suction on. The attending made her first cut. Bull watched, unblinking, from behind his bifocals, his hands clasped against his chest to guard their sterility. The scalpel split the patient’s skin like a zipper, down to the fascia, to the muscle, to the bone. Suction off. An energetic stillness, a focused silence, descended on the room—the silence not of a sanctuary but of a science exam. “Give me the worst fracture there is, and as long as the pieces of bone are still in the body, I feel like I can put it back together,” Rob Wylie, an orthopedic surgeon on the team, said. “Fractures, for me, are so cool—it’s a puzzle, and it usually has a solution. Actually, it has multiple solutions that are acceptable, and one that is better than all the rest. I like to find that.”

Bull is a patient teacher, hard to faze. When the attending missed the bone with a screw, he smiled and encouraged her to try again. When the resident grew frustrated trying to fit the puzzle-piece fragments together, Bull gently reminded him not to let perfect be the enemy of good. Two plates and six screws later, the joint was back in place. Bull showed the orthopedists how to use a suture anchor to repair the ligament, to prevent chronic dislocations in the future.

Afterward, still in his scrubs, he sat on the roof of the hospital, sipping rum from a reusable Starbucks cup and watching the city lights. In the courtyard below, patients’ families spread sheets out on the concrete, bedding down for the night. Somewhere far off, a siren wailed. “I just see us all as one,” he said. “A comment I get with some regularity back home is ‘How can you go to Haiti when we have problems here in Flagstaff, or we have problems here in the United States?’ And I understand that perspective—I accept that, I honor that. To those people who might be open to the concept, I just say, ‘My bubble’s bigger. It’s not better, it’s not worse, it’s just bigger.’”

Leave a Reply