Room 235 in Bicentennial Hall contains the biology department’s collection of preserved invertebrates, one of the most significant being the Duncan J. McDonald Insect Collection. The McDonald Collection resides in a large metal cabinet that stands about seven feet tall and contains two rows of stacked wooden drawers, 48 drawers in total. There are thousands of insects here, many of which were collected and preserved by McDonald himself, a biology professor at Middlebury from 1967 to 1985.

“Professor McDonald’s contribution to the biology department has been unique,” states the honorary minute that was written upon his retirement in the spring of ’85. “In contrast to the conventional professionalism of the other members of the department, he has been a generalist, a nonconformist, and an original thinker.” McDonald died in 2005; those who knew him at Middlebury, including the recently retired Tom Root and emeritus professor Chris Watters, each chuckled at the description of their former colleague, citing the observation as accurate.

“In the most fundamental sense of the term, he was a natural historian,” says Watters. “He was a lifelong learner and enjoyed being a contrarian. And he always enjoyed contributing to the conversation, whatever that conversation may have been.”

And, in a way, his collection has been continuing a conversation ever since he arrived in the summer of 1967 and began collecting insects.

“The collection is an extraordinary asset to illustrate the great diversity of insects in Vermont and, by extension, the world, in our courses,” says Tom Root. “While the collection correctly accumulates many specimens within each taxonomic group or order of insects, we also take selected examples from each of those to illustrate all of the orders at one time.”

At a glance, the viceroy butterfly could be mistaken for the monarchs that appear in the previous image, an act of mimicry that is intentional on the insect’s behalf. Spritzer, the department chair, uses the collection in his course on animal behavior, using butterflies—with specific attention paid to their wings—to illustrate instances of cryptic coloration and mimicry.

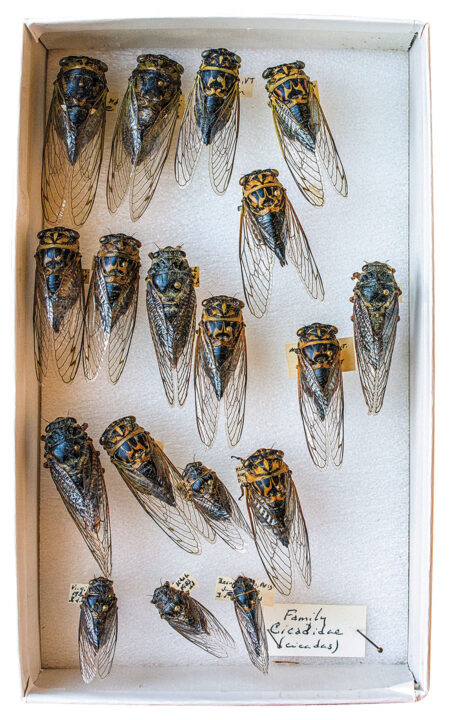

Cicadas have been featured in literature since the time of Homer; Ellery Foutch, an assistant professor of American studies, has used the collection in several of her courses, including the first-year seminar Mermaids, Mummies, and Mastodons: Capturing Nature in America. “I ask students to carefully study a specimen, and then they might write a thorough description of it, working on their observation skills and sense of narrative; or they might write an ‘it’ narrative, a story from the perspective of the specimen itself.”

Anna Mullen ’15 and Sadie Coffin ’19 each took Foutch’s class. Mullen calls the experience “an academic delicacy: a rare (and neglected) kind of intimate inquiry . . . and one of the most generative things I did at Middlebury.” Adds Coffin: “I loved the investigative feeling of uncovering stories about the collector, learning about the science behind patterns on a butterfly’s wings, and studying the broader cultural significance of the creature.”

These spider wasps, commonly referred to as tarantula hawks because females will hunt them and lay their eggs on the spider corpse, are indigenous to the southwestern United States down through Mexico and into Central America. McDonald collected these specimens during a summer research trip to southern Utah and northern Arizona.

“The artistic value of the collection should not be minimized,” says Tom Root. “It is used as a goal when students start their own collections to illustrate the exacting techniques used to mount specimens in specific ways so that they best display their anatomy—but also their beauty, as well.” We close this photo essay with these dragonflies. It is, indeed, a beautiful display. Further, the specimens here were not only collected by Duncan McDonald (in Vermont between 1968 and 1984), but also by his students, James Douglas ’79, Julie Alden ’84, and Diana Hegarty ’85.

Leave a Reply