From the bed where she’d been confined for several weeks, my mom related a story to visiting well-wishers. I’d been warned when I left for college that if I ever came home with a beard, I wouldn’t be allowed inside. I returned one holiday with some scruff on my cheeks, and Mom made good on her threat. Banished, I retreated to my grandparents’ home, removed the scruff with my grandfather’s aged Norelco, and presented myself again. This time I was welcomed, a clean-cut prodigal son.

Though my memories of this event are foggy, there’s no question that Mom harbored a strong distaste for facial hair. When my father grew a mustache in the mid-’70s, it was a dozen years before she’d kiss him on the lips. This was also the time when she was diagnosed with the first of four cancers, which would appear every 10 years, like clockwork.

I remained clean-shaven through my 20s. But my 30th year saw a change. Whether it was the spirit of San Francisco (where I’d relocated) or fond memories of the circa 1972 Jerry Garcia poster that hung in my Battell room, I can’t say. But I put my razor aside and let the facial hair fly.

There was mild disgust in Mom’s eyes when I appeared at her Florida condominium, and there was certainly no kiss. Protestations that under the beard I was still the same person that she had loved so much cut no ice.

My mom never explained her aversion to facial hair. She’d allude to beards as being not neat—as though beards were nothing in themselves beyond a negation of a clean-shaven something else. I suspect they spoke to some undesirable/uncouth otherness for a woman who came of age during the Eisenhower era: Working class? Hobo? Beatnik? Cult member

I’m sure she was also concerned about my career, how her only child’s facial mane might impact his job opportunities. What doors would a beard close? It was as much about me as it was about her.

When my wife and I moved to Portland, Oregon—a land of many outlandish beards—in the aughts, Mom’s position seemed to soften. Bearing facial hair was not necessarily the mark of a heretic or pariah. This was underscored when she and my father attended a presentation for my first book at the venerable Powell’s Books store. Many in attendance wore facial hair. Some even wore ties.

Last winter, after an unsuccessful round of chemo, Mom’s oncologist gave a grim prognosis—six months to a year of life without more treatments; one to two years with aggressive chemo. At 87, she opted to forgo treatment. I increased the frequency of my cross-country visits.

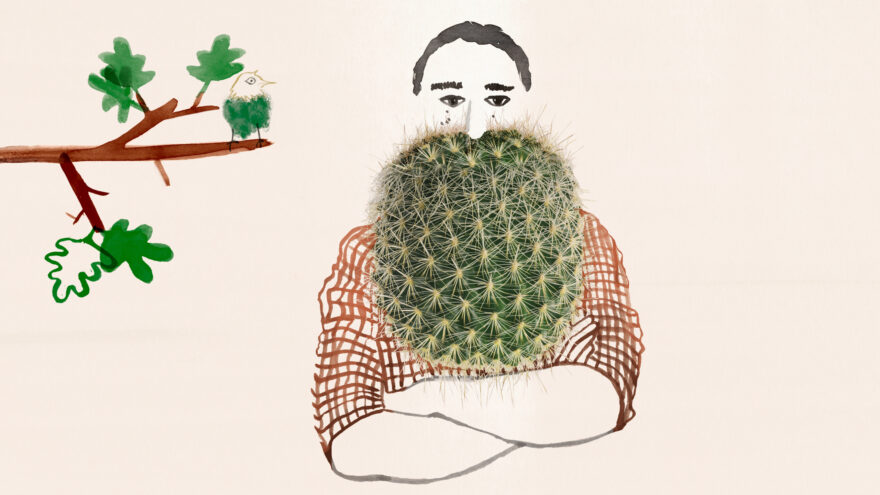

The notion of shaving my beard “for Mom” had come up on a number of occasions as her inevitable end approached. At first I opposed the idea. Was there some battle of wills between mother and son that remained unresolved?

The afternoon before my wife and I were to depart for Florida, I stood before my bathroom mirror, Groomsman in hand. A beard could be grown back; there was a small gift I could give.

That afternoon, I crossed the threshold of my mother’s home with none of the shame or sense of defeat I’d experienced more than half a lifetime before. When I entered her room, she was curled up in a fetal position, facing away from the door. “Your son’s here, and he’s got a surprise,” my wife announced.

I crawled onto the bed, as Mom was unable to turn herself. She opened her eyes, smiled, and patted my cheek.

“That’s my baby,” she whispered.

Leave a Reply