The note reads, “Bill again—what a man!”

It is scrawled beneath a warning slip issued to Ingrid “Inki” Monk Stevenson ’44 on February 27, 1941, that cites her for missing curfew by one minute. Inki’s note lays the blame on Bill, whoever he was—but the wording suggests she wasn’t too mad about it.

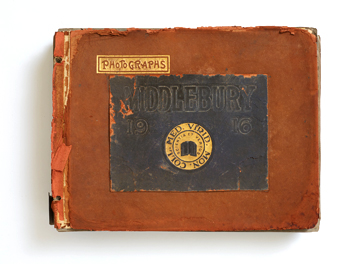

The warning is just one of many mementos that Inki glued to the pages of her Middlebury scrapbook, which her daughter, Connie Gottwald, donated to the College in 2015. It’s part of the exhibit Scrapped!, on display in Davis Family Library. Curated by students Ambar Vasquez-Mitra ’25 and Yvette Fordjour ’26, the exhibit features scrapbook pages dating from the early 19th century to recent decades; they hold whatever small items students deemed memorable during their undergraduate years, everything from notes and invitations to report cards and photographs.

The initial idea for an exhibit came from Mikaela Taylor ’15, public services and outreach specialist for Special Collections, who was looking for an opportunity to make use of the many scrapbooks that had been donated to the College over the years. The majority came from the alumni who had created them, from their families, or from graduating students whose scrapbooks pertained to clubs or organizations on campus.

In October 2024, Taylor presented Special Collections student employees Vasquez-Mitra and Fordjour with access to the entire collection of scrapbooks and asked whether they’d like to build an exhibit around them. The two were overwhelmed at first. “For a good minute,” Vasquez-Mitra says, “we were just looking through the pages, just reading, trying to see what people were saving. We realized that a lot of the things that were preserved in the pages were kind of funny, or things we’ve experienced in our own college time.”

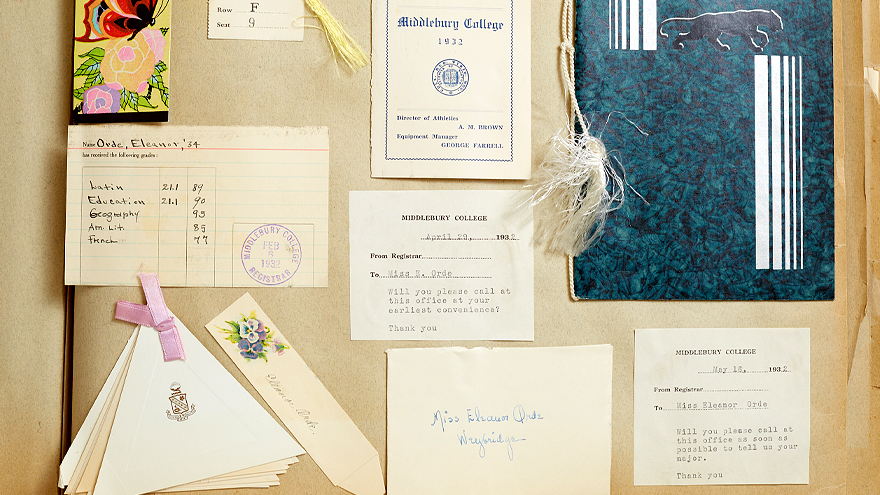

Vasquez-Mitra, a history major double minoring in art history and museum studies and Portuguese, took me through the exhibit, which greets visitors when they enter Davis’s main floor and continues downstairs in Special Collections. After considering a few different approaches, she and Fordjour picked a number of themes—including “Sports,” “Winter Carnival,” “Reconciling the Past,” and “Dorm Life”—and chose scrapbook pages that fit those themes.

Vasquez-Mitra liked seeing what different students thought was important enough to keep. Many scrapbooks feature pressed flowers and confetti from parties, mementos that would have no context for anyone except the saver. Other items remind us how much has changed: for example, dance cards, relics from a bygone era when young men had to reserve turns on the floor with desired dance partners. But the exhibit also reminds us how much has stayed constant, juxtaposing pages and photos from similar events, such Halloween dances, that occurred decades apart.

Some students saved their grades, progress reports, course warnings, GPA calculations, and even notes on what they’d need to score on a certain exam to pass the class. “Academic stress,” Vasquez-Mitra says, “is timeless.”

While the scrapbooks show the throughline of college experiences from Middlebury’s earliest days, they also highlight cultural shifts from the 19th century to the 21st. “We are very much aware that these scrapbooks are a product of their time, and of the social norms that were acceptable,” Vasquez-Mitra says. She points to the “Women’s College” display, which shows how the first co-eds at the College were heavily policed, from their social habits to their clothing; and to “Reconciling the Past,” which reveals casual attitudes to racism and colonialism that today look starkly offensive.

In the corner of a placemat-size 1930s pen-and-ink map of the campus, for example, a brief history of the College hails Gamaliel Painter’s arrival to Middlebury with an apocryphal tale claiming that he drove out all the wild animals (except the panther) as well as the “Injuns.” A cartoon illustration—considered humorous at the time, cringe-inducing now—shows a man with a gun chasing three fleeing Native Americans.

Vasquez-Mitra thinks it’s important to include these darker aspects of Middlebury, once celebrated in print and in song, even if they make us uncomfortable today. “Middlebury has this history. It’s also attempting to move forward, through the land acknowledgment and learning more about the past.”

Choosing what to include in the exhibit was a large part of the challenge; Vasquez-Mitra and Fordjour worked many hours from October through J-term pulling the exhibit materials together. But Fordjour had to leave for a study away semester before the exhibit was launched, so it fell on Vasquez-Mitra to set up the displays. She turned to Taylor and Joseph Watson, preservation manager for Special Collections, for guidance in everything from the physical setup and label writing to exhibit promotion.

Watson taught her how to handle and preserve the delicate paper and materials in the scrapbooks, which he says were not easy to display. “Many of them are large, and sometimes they’re not in the best condition because the people who originally made them looked at them a lot over the years,” he says. “Plus many of the contents, like a place card or napkin from a party, were meant to be used once and discarded, so they’re not sturdy. And there are a lot of odd-shaped things included too, like dried flowers, candy, paper hats, matchbooks—there’s even a cigarette.”

Fordjour, a junior Black studies and English double major, says they joined Special Collections last year “not knowing the importance of the archival record as it pertains to institutional and cultural history.” They learned a lot about the technical aspects of curating an exhibit as well as a lot about Middlebury students: for example, how students during World War II perceived the general war effort and how that played out in their scrapbooks. “Especially when thinking about my fields of study, I find the possibilities that archives hold for gleaning unique and highly personal perspectives particularly rewarding and enriching.”

Fordjour enjoyed the time planning the exhibit with Vasquez-Mitra. “It was such a pleasure working with her and building these different cases that highlighted the expansiveness of Middlebury history, both the beautiful and the ugly.” And they recommend that current students check out Special Collections for themselves. “Its vast collections hold so much potential to see oneself represented.”

Taylor says that in recent years Special Collections has been trying to get more students involved in curating exhibits, not only for preprofessional experience, but also for the fun. She says once she showed Vasquez-Mitra and Fordjour the scrapbooks, “they took off running with the idea and made it their own. They went above and beyond what I could have imagined.”

She also expresses gratitude for the past students who preserved the seemingly trivial things that mattered to them. “These physical, material memories are important. We wouldn’t be able to tell this story if students didn’t save the little papers and ephemera and stuff they considered important.” She encourages today’s students to hang onto such things as well. “Having something physical to hold or look at means being able to get semi-close to what these students were thinking and feeling. It’s not the same as looking through a phone screen and taking a picture. Maybe consider saving some old junk to keep.”

“Old junk” is a relative term; scrapbooks, almost by definition, contain items saved not for their intrinsic value but for what they represent to the individuals who save them. Take, for example, Inki Monk’s scrapbook. Whatever came of the young romance that not only made her miss curfew that night but also prompted her to preserve and annotate the resulting warning?

It turns out that her sweetheart—“What a man!”—was Bill Stevenson ’44.

Reader, she married him.

Scrapped! is on display at the Davis Family Library and Special Collections through Reunion in June.

Leave a Reply