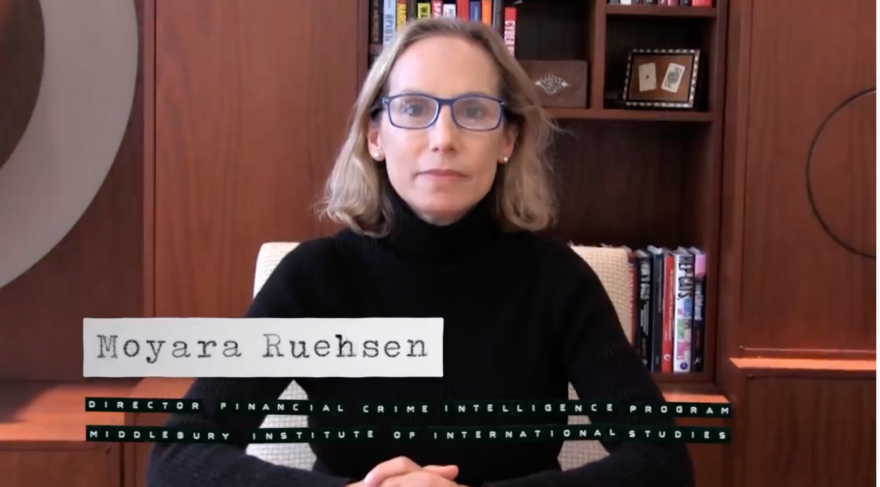

If you listened to this spring’s BBC World Service podcast The Lazarus Heist , you might have heard the voice of Moyara Ruehsen, professor of financial crime intelligence and head of the Financial Crime Management program at the Middlebury Institute (MIIS). In the seventh episode of this 10-part series, which examines North Korea’s 2016 effort to electronically steal $1 billion from the Bank of Bangladesh, Ruehsen explains the general elements of money laundering and which techniques the North Koreans used to try to make their illicitly obtained funds appear legitimate.

Or maybe you saw Ruehsen on YouTube in Vanity Fair’s 2020 series on financial crimes. Her video, “Professor Fact Checks Money Laundering Scenes, from Ozark to Narcos ,” in which she takes a look at how accurately popular TV shows portray money-laundering schemes, has racked up nearly 1.5 million views.

The same qualities that make Ruehsen a popular choice for money-laundering analysis in the media—deep expertise in her field and an ability to make the complex world of money laundering understandable to her audience—also make her a compelling educator. But she says she did not initially plan to go into teaching. As a student, she spent time in the Middle East on a Fulbright Scholarship and earned a master’s in Middle East studies, and she expected she’d work for an oil company or perhaps the World Bank.

Shortly after earning her PhD in international economics and Middle East studies, however, she gave a talk at Berkeley on the subject of her dissertation—the political economy of oil—which opened the door for her to teach there. Although the administration turned down her offer to teach about oil, they agreed to a topic that fascinated her: illicit markets. She spent a year as a lecturer at Berkeley, then took a faculty position at the Institute in 2003 to teach international economics. But she couldn’t stop thinking about the world of financial crime.

While international economics were what she calls her “bread and butter” at MIIS, whenever possible she taught courses on international organized crime, which covers everything from illicit drug markets and arms trafficking to sex trafficking and extortion markets. “I felt like I was wearing a lot of hats, and I thought, I’ve got to concentrate on just one thing,” she says. “And the one thing that excited me most about all of those different topics was the money-laundering piece. That’s what they all had in common. And that’s what I slid into.”

September 11 marked a new trajectory in her career. “All of a sudden you have somebody who understands money laundering—which uses the same techniques they use for terrorist financing—and who has knowledge of the Middle East,” she says. “I was in a really unique position to capitalize on that, and I just suddenly became in demand.”

Ruehsen found herself, in addition to teaching, conducting counterterrorist financing training for the FBI, consulting for the Intelligence Community, and speaking at conferences. Her expertise became even more valuable when North Korea turned to electronic bank crimes (such as the Lazarus heist) to finance its weapons building, as she was one of the early—and largely self-taught—experts on the newly emerging area of cyber-enabled financial crime.

She was instrumental in establishing the Institute’s Financial Crime Management program, and she currently teaches trade-based financial crime, cyber-enabled financial crime, and financial crime investigation, including compliance management.

Ruehsen says students interested in careers investigating money laundering—including counterterrorism financing and counterproliferation financing—often assume they’ll need to learn things like forensic accounting (a separate field). What they really need, she says, are a healthy dose of curiosity, a good grounding in geography, and general knowledge about the world.

International banks, for instance, are responsible for detecting and reporting financial crimes, including sanctions violations. Criminals will often try to obfuscate information on the documentation that the bank’s trade finance department sees, but an employee with a good grasp of geography will notice if place names have been entered in a suspicious way or if a ship takes a circuitous route that stops in an unusual port such as Vladivostok, the closest large seaport to North Korea.

Ruehsen advises prospective students, rather than reading books on money laundering, to read the Economist regularly as a way to keep up with everything from politics and culture to science to the environment. “It’s that general knowledge that makes for a great investigator,” she says, “because they will notice something unusual, which somebody who doesn’t have that general knowledge won’t notice.”

She estimates that about a third of graduates of the Financial Crime Management program go on to work for government agencies such as the Intelligence Community, FBI, DEA, or Homeland Security. Others start at traditional banks, working their way up to special investigations or perhaps jumping to fintech (financial technology) companies, such as PayPal or cryptocurrency exchanges. She’s been at the Institute long enough that former students who took her money-laundering class and pursued careers as investigators are now hiring recent Institute grads. “We call it the MIIS Anti-Money-Laundering Mafia,” she jokes.

As technology advances, so do money-laundering techniques. “In the old days, when people sold drugs on the street corner, sure, you’d get a lot of cash,” Ruehsen says. “In fact, drug revenue is the number one criminal revenue we’re looking at. Now people buy drugs online. So a lot of that revenue is coming in in the form of cryptocurrency.”

The purported anonymity of cryptocurrency makes it a natural avenue for money laundering. That in turn has given rise to the field of blockchain forensics. Ruehsen says, “These are companies that have their own proprietary software to trace and map all of these cryptocurrency transactions to illustrate how the criminals are laundering the funds and where the money is going, to which wallets and which exchanges.”

Ruehsen is particularly pleased with how one of these companies, CipherTrace, is collaborating with the Institute and a handful of other schools. The CipherTrace Defenders League trains students in blockchain forensics through what is essentially a pro bono clinic. Students then earn academic credit by taking on real-world cases that are typically too small for law enforcement to investigate—such as helping someone whose elderly relative has been the victim of a phone scam. Ruehsen calls it a “win-win.”

With money launderers constantly finding new ways to get around the law, experts have to work hard to keep up. “There’s an expression we use in law enforcement: ‘You sharpen the spear, and the criminals invent thicker shields.’”

Leave a Reply