When the Middlebury College Museum of Art reopened to the public on April 15 after a two-year closure due to COVID-19, I went for a visit. As soon as I entered the first of the three main-floor galleries, I could see something was different.

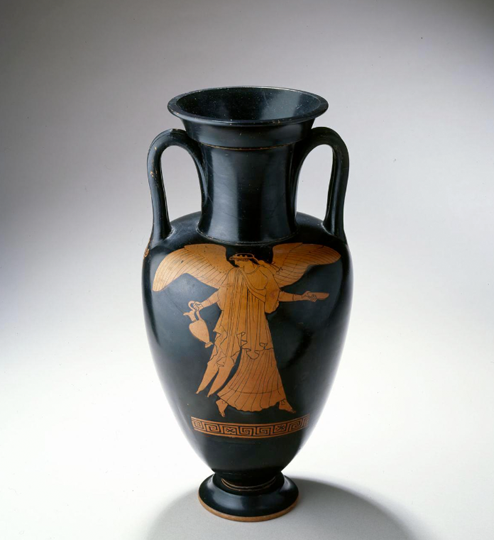

Generally, in museums, exhibits focus on a particular artist, era, region, or style. Here, however, instead of rooms entirely devoted to Van Gogh or ancient Egyptian art, were collections spanning more than two millennia, by artists from across the globe. The pieces were grouped under such broad themes as “The Art of Storytelling” and “Death and Remembrance.” A casual museumgoer at best, I was not prepared for the effect this new setup would have on my experience of the art.

The juxtaposition of such disparate works, ancient and modern, realistic and abstract, could have come across as disjointed. Instead, it highlighted what the pieces had in common. In “The Art of Storytelling” exhibit, for instance, seeing how artists across time and place shared the human impulse to portray narrative in their work, it struck me that we all share the same creative spirit. It binds us to the rest of humanity—those we know, those we don’t know, and those who came before us. This thought was either profound or ridiculous; I wasn’t sure at the time.

When I returned to the museum a couple of weeks later for a one-on-one tour with Museum Director Richard Saunders, I sheepishly tried to explain that deep feeling of connection I had felt with the artists represented in the museum. Saunders just nodded. “That tells us that our concept is working,” he said. “What we want to do is establish threads.”

Ironically, the opportunity to create new connections for museumgoers came at a time of sudden disconnection. In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic closed the museum. Once the staff, working remotely, recovered from the initial shock of the shutdown, they started to think about it as an opportunity: “How can we put this time to good use? How can we take advantage of this?” And that was the beginning of several sweeping changes.

First, staff completely reinstalled the permanent collection. The museum returned to its former practice of housing that collection on the main floor and putting the changing exhibition space upstairs. This way, while a new exhibit is being installed on the upper level, as happens every few months, the main floor can remain open.

Second, staff set out to make the museum more accessible—both physically easier to navigate and more inviting to a wider audience. Saunders explained that while the museum had not changed much since its move to the Mahaney Arts Center in 1992, the student body had. “The installations served their purpose,” Saunders said, “but it was time to step back and say, ‘OK, how can we embrace diversity? How can we embrace inclusivity? How can we embrace accessibility?’”

In response to those questions, staff examined physical access to the museum. To accommodate people using wheelchairs, they hung artwork lower. To help people with visual impairment, they increased the font size of the labels accompanying each work. They also displayed fewer items, giving the gallery more visual and physical space.

“But even more, or equally, important,” Saunders said, “we decided we needed to make sure that anyone who comes into the museum is welcome and welcomed by objects that they can relate to,” even if they’ve never been in a museum before. The museum’s new approach—an effective one, as I had discovered firsthand—was to arrange objects by theme, rather than by geography or chronology.

“That means that you don’t have to know anything about art to find something here that engages you,” Saunders said, “because the thematic issues are very broad, whether it’s materials or whether it’s the act of creativity or whether it’s something defined as a portrait. What’s a portrait?”

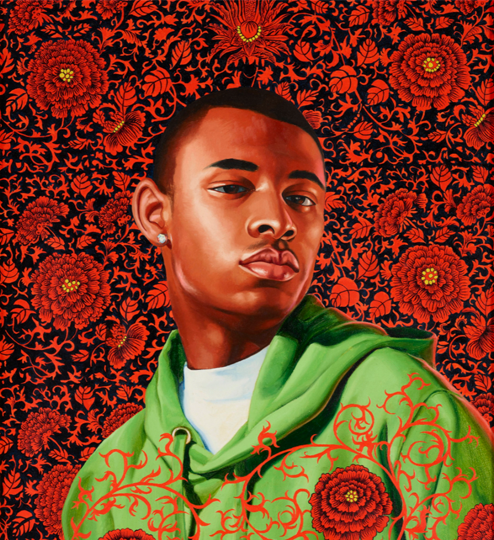

Saunders took me past a series of portraits, interpreted in different styles and media but all depicting the human form: an ancient Egyptian wax portrait, a 17th-century Dutch paint on panel, a marble relief by an artist who was born in Vergennes and became one of the first female artists to work in Italy, a selection of early Vermont daguerreotypes, and a painting by Kehinde Wiley, who also painted Barack Obama’s official presidential portrait. In the past, most of the artists represented would have been white males. No longer. “We have a responsibility to show greater ethnic diversity, racial diversity, more gender balance,” Saunders said.

He added that while other museums are slowly beginning to adopt this thematic approach, Middlebury is among the first. “I think because we’re smaller, and because we had this opportunity during COVID. We jumped on it and said, ‘Let’s do this now.’”

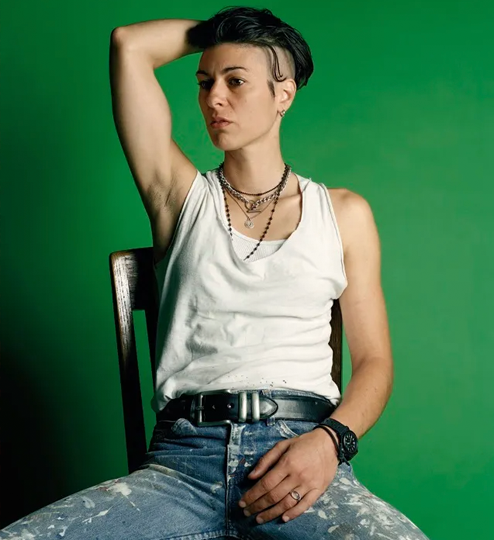

Broadening the diversity of artists on display is only one part of the museum’s efforts to promote inclusivity; staff are also seeking to expand the conversation about those artists and their works. To that end, Jason Vrooman ’03, curator and director of engagement, developed the “Label Talk” series. A selected Label Talk piece, instead of being accompanied by a single, staff-written label, displays several short descriptions, each written by a different person and offering a unique perspective.

As an example, Saunders showed me Untitled (with Red), a brightly colored aluminum sculpture. “In the case of this work by an artist from Ghana, El Anatsui, we have three different texts. One is by Chris Murray, who’s one of our preparators. And then we have two texts by Middlebury College students, both of whom are from Ghana. So that way, we have a more inclusive discussion of what’s on the wall, depending on your vantage point.”

The Museum of Art’s use of Label Talk was mentioned in a November 2021 New York Times article on how museums are beginning to use labels in new ways to engage more diverse audiences. Writer Julia Jacobs explained the value of including different viewpoints: “In a period of intense self-examination at institutions around issues of race and equity, curators say that a short museum label can crystallize some of the existential questions institutions face right now: Who is equipped to write authoritatively about this work? Who is this label being written for? And how do we give over this platform to people who haven’t previously had it?”

Saunders wouldn’t call the long closure of the museum a net positive, but he admitted that the downtime offered his team a chance to catch up on larger projects. “We have a tiny staff, and we’re usually like ducks on a pond; you don’t see the little feet working hard to keep you going. . . . This allowed us to step back, and that was healthy.”

He lamented, among other things, the two 2020 exhibits that got shut down by COVID after just a month and the lack of on-site museum interns for the past two years. But Saunders was enthusiastic about the changes the museum was able to make during the closure, changes he hopes will spark in visitors, as they did in me, a deeper connection with the art on display. “I like to say we made lemonade out of COVID lemons,” he said.

The Handbook

The museum recently released its long-awaited guide, the Middlebury College Museum of Art Handbook of the Collection, whose publication neatly coincides with the 30th anniversary of the museum in its current location. A companion exhibit, titled Contemporary to Classical: Highlights from the New Collection Handbook, runs through August 7 on the museum’s upper level.

The 270-page handbook contains photographs and descriptions of about 225 of the more than 6,000 works in the museum’s permanent collection. The book was edited by Richard Saunders, museum director; Pieter Broucke, associate dean for the arts and professor of history of art and architecture; and Sarah Briggs ’14.5, the museum’s former Sabarsky Fellow. With contributions by 76 authors, including President Laurie Patton, the handbook features works that reflect the growing diversity of the permanent collection. It is currently available for purchase at the museum.

Leave a Reply