This past May, while students in some courses were studying for exams or writing final research papers, students in Professor Eliza Garrison’s art history class on the Bayeux Tapestry were wrapping up the semester with an intense group project they had chosen for themselves: a half-scale pencil-and-paper facsimile of the 11th-century masterpiece that illustrates the Norman Conquest of England in 1066.

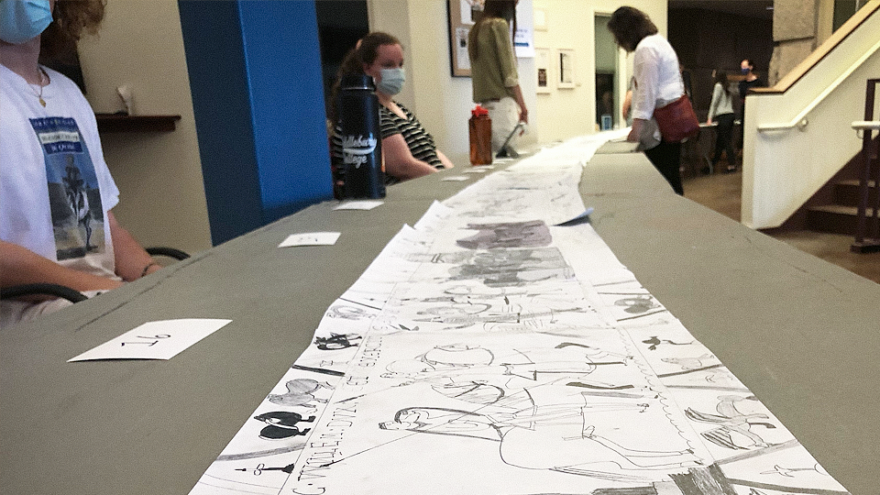

On Thursday, May 20, the class held a public poster session to display their creation, rendered on sheets of copy paper taped end to end and snaking out of sight through the lower lobby of the Mahaney Arts Center. As viewers worked their way left to right along the 115-foot-long drawing, students were on hand to narrate the scenes and translate the Latin inscriptions.

The course, The Bayeux Tapestry: Models, Contexts, and Afterlives, centered on a close analysis of the 20-inch-high, nearly 230-foot-long tapestry, which dates to roughly 1070 AD. Garrison envisioned the tapestry as a prompt for her students, a “jumping-off point for various questions that people who work in the humanities generally ask: How do we know what we know? Why is a particular line of argumentation about the work accepted over others? Who made this artwork? What was involved in its making? Who had it made? Who is deemed worthy of representation, and who isn’t?”

Comprising 59 scenes, the tapestry depicts the events leading up to and including the invasion of England led by William, Duke of Normandy, culminating in the English defeat at the Battle of Hastings. Framed by top and bottom friezes decorated with real and fantastical creatures, the scenes feature skillfully sewn images of castles and ships, feasts and a funeral, noblemen and peasants, knights and archers, and too many horses to count. Halley’s Comet even makes an appearance.

The piece is, technically, an embroidery, not a tapestry; the images were fashioned with wool yarn stitched onto a plain linen background, not woven into the fabric itself. Janice Zhang ’21 said the class did in fact refer to the piece as the “Bayeux Embroidery,” but not just for semantic accuracy. “It gives more power and credit to the historically erased labor of the women who worked on it,” she said. “Embroidery was seen as women’s work.”

Due to COVID-19, the class met remotely in the early weeks of the semester. But eventually Garrison was able to introduce more interactive components to the course. Robin Foster Cole and Carol Wood of the Theatre Department, for instance, helped her brainstorm a three-day session on medieval embroidery techniques and created a dyeing demo.

In the final weeks of the semester, the class divided the tapestry up into sections, with each of the 13 students—as well as Garrison herself, who said she felt she needed to “have some skin in the game”—taking on four to six consecutive scenes and recreating them as faithfully as possible in pencil.

During the poster session, in addition to explaining the significance and context of the scenes along the tapestry, students shared their thoughts on their individual areas of focus, which ranged from the lack of female representation in the tapestry to the history-is-written-by-the-winners bias of the narrative. They discussed the knowns and unknowns concerning the tapestry’s origins as well as the limitations of their expertise, given that only one student had seen the tapestry in person. And they admitted that copying the tapestry in pencil turned out to be far more challenging and time consuming than they had anticipated.

Garrison explained that the facsimile wasn’t meant to be a test of students’ artistic skills but rather a way to more deeply study the tapestry. “I wanted to make sure students emerged from the class with a capacity to look closely and to see what kinds of questions emerge as one becomes familiar with a particular thing,” she said.

Despite the difficulty of drawing the tapestry, students unanimously recommended that Garrison integrate the same final project the next time she offers the class. “What I hadn’t realized is just how invested the students were in it,” Garrison said, “and I also hadn’t realized that it became a lesson in humility for us all. This thing is huge!”

Rhys Glennon ’22, who illustrated the last five scenes, saw the poster session as a fitting tribute to the tapestry. “I wrote my research paper for the class on the medieval presentation and display of the embroidery, looking at scholarly suggestions that it was displayed in a public place, perhaps a cathedral, during a midsummer feast day,” he said. “I thought this final event perfectly captured what such an event might be like, right down to our role as interpreters of the work to a general public unable to read the Latin inscription or decipher every detail.”

The Bayeux Tapestry, on display at the Bayeux Museum in Normandy, France, can be viewed on the museum’s website.

Leave a Reply