At a spacious gym in suburban Cleveland, the new guy is working overtime, hoping to impress the boss. Larry Nance Jr. is a hyper-athletic six-foot-eight forward still getting used to his new surroundings. His teammates have hit the showers, but Nance is still on the court, sweating through an extended postpractice skill session with a couple of assistant coaches. One feeds him a pass or provides a screen around which Nance can maneuver; the other mimics a defender, a body for Nance to spin or dribble past en route to the basket. They talk occasionally between reps—about Nance’s footwork, or the efficacy of a pump fake—but from a courtside bench, the conversation is barely audible. The only real noise is the squeak of sneakers and the thud of a bouncing ball, basketball’s fundamental noise, as Nance goes to work again and again.

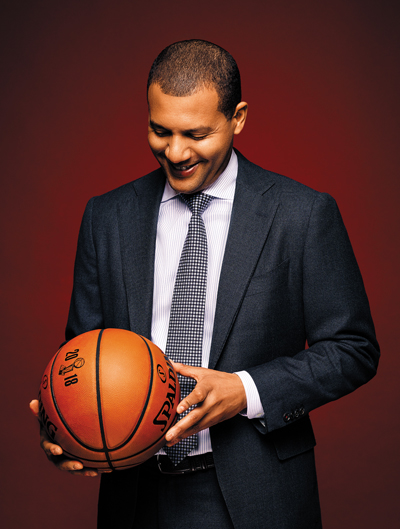

Koby Altman ’04 watches from that bench, sharp casual in gray slacks, a light sweater, and sneakers, his back against the gym wall, his attention drawn occasionally by the vibration of his phone. It’s a damp morning in late February; exactly two weeks earlier, Altman, the Cleveland Cavaliers’ first-year general manager, remade his team’s roster with a pair of trades that jettisoned six players and brought in Nance and three others. The deals were finalized just hours before the NBA’s annual trade deadline, and they dominated conversation around the league; as a rule, title contenders don’t turn over half their rosters with two months left in the season. But the Cavs, at Altman’s command, had done just that.

In the space of a week, public perception of Altman had swung from “young guy in over his head” to “deadline-day genius.” It was hard to tell if observers were more surprised or impressed. Altman was just glad he could finally get some rest.

“As it gets closer to the deadline, you’re not sleeping,” he says. “You’re up until three, four o’clock in the morning, pounding the phones. Could we have done these trades a week before? Maybe, but then you don’t have the mechanism of a deadline.” Until you do. And then? Altman smiles. “It was a chaotic 24 hours.”

The intensity of deadline day was in keeping with much of Altman’s short but dynamic tenure. The league’s second-youngest general manager, he was promoted from assistant GM last July to lead a team coming off its third straight appearance in the NBA finals. That was the good news; the bad wasn’t bad as much as it was almost comically absurd. On the very same day that Altman’s hiring was announced, news leaked that the team’s all-star point guard was demanding a trade. At least Kyrie Irving was only the Cavs’ second-best player. Their best—LeBron James, perhaps the best on the planet—was already the focus of a league-wide countdown to becoming a free agent in the summer of 2018.

There was no exaggerating the size of the challenge. The question was whether Altman—young, relatively unknown, and on the job for literally hours—could possibly be up to it. When he took the Cavs’ top job, he was just five years removed from a no-profile gig as an Ivy League assistant coach. Two years before that, he was folding laundry for a USA Basketball junior team. Three years before that, he was selling real estate. And three years before that, he was wrapping up a decent if unremarkable playing career at Middlebury.

On paper, the pace of Altman’s rise almost defies belief, but it’s less of a mystery to those who know him. Longtime friends, ex-teammates, and former bosses all cite a rare mix of intelligence, work ethic, confidence, and, especially, an enviable ability to connect.

“He’s an incredible people person, and an incredible communicator,” says David Griffin, Altman’s predecessor as Cavs’ GM. Debbie Bial, whose Posse Foundation was instrumental in bringing Altman to Middlebury, describes his “unique ability to make people feel comfortable no matter what the topic of conversation is.”

There’s more to his success than just networking, of course, and in his first nine months on the job, Altman called on an array of skills to steer the franchise through tumult, apathy, and potential ruin. In the midst of all this, he and his fiancée welcomed their first child, a daughter who would spend the first seven weeks of her life in neonatal intensive care. Few people knew that story, and that was intentional; Altman didn’t want the most difficult weeks of his life to be seen as a distraction or an excuse during the most challenging period of his career.

As we write this, on the eve of the playoffs, it’s too soon to tell whether Altman has done enough to see the team back to the finals, or to keep LeBron from leaving (again). He might be mere months away from ending his first season with a championship. He might be nearly as close to having to start from scratch. (Ed: On May 7, the Cavs completed a sweep of the Toronto Raptors to advance to the Eastern Conference Finals.)

Koby Altman was born in Brooklyn in 1982, the only child of Deborah Altman, a social worker at Sheepshead Bay High School. His father wasn’t in the picture, and Altman describes his upbringing as lower middle class but stable. “My mom was very strong and independent, and she had to work her ass off, but we had what we needed,” he says. “I was in a very loving household.”

Deborah Altman did everything she could to fill the parental void, building a network of male colleagues and friends who might provide Altman with the paternal example he otherwise lacked. But she did plenty on her own, including passing on an obsession with basketball that she’d developed as a grad student at the University of North Carolina. “She was a huge Carolina fan, and when she moved to New York, she became a huge Knicks fan,” Altman says. He’s fond of telling the story of how, when he was a few months shy of his third birthday, his mother woke him up with a celebratory scream: the Knicks had just won the NBA’s draft lottery, guaranteeing them the top pick in 1985.

“Woke me up in my crib—that’s a true story,” he says with a laugh. “I was indoctrinated to being a Knicks fan. That was all her.”

Having inherited that love of the game, Altman took to it enthusiastically. Many of his early memories revolve around a ball and a hoop, from the succession of Nerf hoops he dunked on (and broke) in the apartment he shared with his mother, to the metal backboards and unforgiving double rims at nearby Dean Street Park, where he learned the blacktop game.

“He was a basketball guy since he was tiny,” says Sam Intrator, an English teacher and assistant basketball coach at Sheepshead Bay High. One of those mentors that Deborah Altman cultivated, Intrator has known Altman since the latter was in preschool.

Intrator watched as Altman, never the biggest kid, developed into a natural point guard, complete with the requisite skill set: a knack for on-court leadership, a sense of the bigger picture, and a willingness to distribute the ball. “Good point guards are able to orchestrate things, and Koby’s been a point guard forever,” Intrator says. “Even when he was a little guy, 11 or 12 years old, he was completely connected to what his teammates needed.”

He had the unselfishness you look for in somebody running your offense, and he had great communication skills—you would see that in his interaction with the coaching staff or his teammates.

He was good enough to keep playing once he reached New Utrecht High School, even as he topped out at five-foot-10. (Altman’s blunt appraisal of his own game: “Streaky shooter, good passer, really good handle.”) He held out hope for a basketball scholarship, but he already knew that whatever future he created for himself would depend more on his mental capacity than his jump shot. He wanted to go to a great school, somewhere he’d be challenged, and from where the world would open up for him. A recommendation from another of his mother’s coworkers helped pave the path from Brooklyn to central Vermont.

The suggestion: Altman should apply for a scholarship through the Posse Foundation, a nonprofit that identifies promising students from urban environments and places them on full scholarships at top colleges and universities. Posse now boasts more than 50 partner institutions, but at the time it had only a handful—one of which was Middlebury. Altman endured three rounds of interviews and emerged from among hundreds of applicants to make the final cut. He’d made summer trips to Vermont as a kid to stay with family friends, and he had fond memories of the state. Altman read up on the College’s academics and figured he’d have a chance of making the basketball team. He and Intrator made the trip up from New York City to visit. On first impression, Altman says, “it was like a country club.”

Jeff Brown never got the chance to recruit the player who would go on to start 42 games for him over four seasons. Instead, the Admissions Office gave the Middlebury coach a heads up about an incoming student who might have potential for his program. His scouting report matched Altman’s self-assessment: quick, athletic, can handle and direct his team. Altman would never be more than a pretty good player for the Panthers, but he made an impression nonetheless.

“He had the unselfishness you look for in somebody running your offense, and he had great communication skills—you would see that in his interaction with the coaching staff or his teammates,” says Brown, who recently completed his 21st season. “He was really popular with his teammates, really genuine. He was so self-assured and confident in his ability to relate.”

Chris Matthiesen ’04 remembers Altman similarly—well, mostly. “I used to give him grief for dribbling too much and not passing—typical New York point guard,” Matthiesen says with a laugh. Now a policy advisor with a D.C. lobbying firm, Matthiesen arrived on campus just as Altman did, in the fall of 2000. “You wouldn’t have known anything about his background based on the way he interacted with anyone,” Matthiesen says. “He just fit in. Even with athletes and nonathletes, there’s not always a huge overlap there. But he transcended that.”

If that ability to read and relate to nearly anyone was an inborn skill, Altman honed it in college. It would serve him just as well as he embarked on the only logical career for a hoop-obsessed sociology major: commercial real estate. Laughing at the unexpected first step in his career path, Altman says, “I thought maybe I should use this education and go make some money.”

He did just that, parlaying a connection into an internship at the Manhattan firm Friedman-Roth. Three months in, he’d sold a $2 million property in Brooklyn, seen his first commission, and decided it might be worth sticking things out for a while. He stayed for three years, finding the work a fit for both his quick mind and his competitive fire, never realizing he was training for a dream job in basketball. He was just out of college, living back in his hometown, making real money. But it didn’t take long, hardly more than a year, to realize that he missed the game.

From his office in Chelsea, Altman called Joe McGrane, head coach at Manhattan’s Xavier High School, where Altman had attended basketball camps as a kid. He had an offer, or rather, a request: Could he help out with the team? McGrane was happy to have him, and so Altman would sneak out of the office for an hour in the afternoon and walk the four blocks to Xavier, assisting with the school’s first-year team. Soon enough, an hour turned into two, afternoons became weekends. And Altman knew. “It just sparked it back for me,” he says. “I was like, This is what I need to be doing. I don’t care how much money I’m losing. This is what I want to do.”

Even as he kept his real estate gig, Altman started making plans. He called Intrator, who by that point was a professor of education and child studies at Smith College, and who had also started a nonprofit aimed at developing coaching skills in inner-city youth. Intrator encouraged him to go back to school, even as he acknowledged the “huge professional risk” of leaving a lucrative career still in its early stages. “From the outside, it looked like he was made to work in real estate,” Intrator says. “But he followed the call of what he was passionate about.”

And so began Koby Altman’s decade-long crash course in basketball administration. He signed up for grad school, enrolling in the sports management program at UMass in part because it would allow him to coach; coaching, he thought, was what he wanted to do. In the fall of 2007, he joined the staff at Amherst College, where Dave Hixon had just led the Mammoths to a Division III national championship. He quickly proved he belonged in an environment where winning was expected.

“I liked him immediately,” says Hixon, now in his fifth decade at Amherst. “I loved his competitiveness—almost an aggressiveness. He was just always competitive. If practice slacked a little bit, it’d tick him off. He couldn’t understand why the kids weren’t playing hard.”

Altman spent two years on Hixon’s staff, completing his master’s along the way. In 2009, he left for a grad assistant spot at Southern Illinois, an entry-level job that allowed him to move up to the Division I level. That was also the year he secured the first of two side gigs with USA Basketball junior national teams. A few years removed from managing multimillion-dollar Manhattan real estate deals, Altman found himself in gyms in New Zealand and Germany, washing towels for a bunch of teenagers. “It was an unbelievable experience,” he says. “And I was the best towel washer.”

The jokes come easy, but for Altman, even that humble gig was proof that he could hang at a higher level: That 2009 Under-19 team featured big-name college coaches and a handful of future NBA players. “When I realized I could navigate that space, that was a big moment for me,” he says. His postcollege path might look like a doubled-over line of progression and regression, starts and stops, but Altman was always learning: It was all progress, all building, all growth. He’d gotten smarter at every step, gained confidence and clarity. He realized he could do just about anything. And then he figured out the thing he really wanted to do.

He started, once again, at the bottom. David Griffin remembers interviewing Koby Altman for what was essentially an internship, working in the Cleveland Cavaliers’ film room. This was 2012, and after that single season at Southern Illinois, Altman had coached two more years as an assistant at Columbia. But the NBA had always fascinated him. He’d decided he was ready to make the jump.

At that point, Griffin was the Cavs’ VP of basketball operations; he offered Altman a couple of jobs before he accepted the role of pro personnel manager. “I loved his background,” Griffin says. “You could tell that he was really mindful of how he was going to be impactful. And from a people standpoint, he just was a natural.”

Title aside, Altman’s job meant scouting—lots and lots of scouting: in his first month, he was on the road 20 days. It was another crash course, learning the language and pace of the professional game, as played on the court and behind the scenes. The Cavs were struggling when he arrived, two years removed from the departure of LeBron James to Miami. But with talented young point guard Kyrie Irving to build around, there was hope in the team’s front office for slow, steady improvement. And Altman was going to be an integral part of it: A year after he was hired, the Cavs promoted him to director of pro player personnel.

And then things got interesting. LeBron James, the Ohio native and consensus greatest player in the game today—not to mention the guy who’d spent his first seven seasons in Cleveland before leaving for sunshine and championships in Miami—came back as a free agent. Griffin by that point was the team’s GM, Altman one of his two trusted deputies, and Griffin says it was very much a group effort by the front office that put the Cavs in position not only to bring back James as a free agent, but to reshape the roster around him.

That was 2014. LeBron led Cleveland to the finals the following summer, and the Cavs went one better in 2016, winning the NBA championship for the first time. That fall, Altman was promoted to assistant GM—a position he would hold for all of 10 months. He’d turned a lifelong love of basketball into a career, he was more successful more quickly than he could’ve imagined, and it had rarely been boring. But this? This was something else entirely.

And then came that flurry of deadline activity: two trades involving five teams, 10 players, and two future draft picks. For the Cavs, it was the basketball equivalent of a defibrillator.

A damp February morning has turned into a chilly evening on the shore of Lake Erie. It’s 90 minutes before tip-off at Quicken Loans Arena in downtown Cleveland, and Altman is courtside, dressed now in a suit, nursing a paper cup of coffee as he soaks up the pregame scene. “I grew up fighting to get to the 300 section in the Garden, and that was a thrill,” he says of the nosebleed seats at the Knicks’ home arena. “So this never gets old to me.”

It might not look like he’s working, but Altman says such moments are vital to his job. He’s watching the players warm up and taking mental notes: How do they carry themselves? Are they focused? Do they seem to be having fun? Griffin, his old boss, had a line about scouting: it’s ultimately about “brokering intelligence.” For the players already on the roster, and those who might someday be, it’s less about what they do in the game—almost anyone could figure that out—and more about “who they are.” Griffin says Altman excels at that part of the work.

And good thing. In the summer of 2017, with the Cavs fresh off a third consecutive finals appearance, Griffin stepped down when he and team ownership couldn’t come to terms on a new contract. The clock was already ticking on LeBron’s free agency, barely a year away, and now Cleveland’s front office was rudderless. And his replacement was . . . who, again? League insiders and plugged-in reporters knew Koby Altman’s name, but few beyond that circle could’ve picked him out of a lineup. But there he was in late July, the next man up.

On that same July day, news broke of Irving’s trade demand. Altman recalls, “I was getting texts from friends: Congrats, that’s amazing! Now what are you gonna do about Kyrie?”

The immediate task: Trade arguably the best young guard in the game for something resembling equal value, a near impossibility considering Cleveland had virtually no leverage; teams knew that the Cavs had to make a trade and would try to gouge them appropriately.

Altman ultimately decided his best trade partner was a division rival, the Celtics, who offered an older and slightly less dynamic scoring guard in Isaiah Thomas. Almost immediately, it appeared the Cavs had gotten fleeced: while Irving played at an MVP level, Thomas missed the first half of the season with an injury. When Thomas finally did join his new team, it was quickly apparent that the fit was wrong, and signs of locker room discord in Cleveland grew too obvious to ignore.

As Altman would say later, “It felt like we were marching toward a slow death.”

As if trying to fix his dysfunctional roster on the fly weren’t enough, Altman also had unflattering headlines to contend with. In the weeks leading up to the trade deadline, a writer for the Athletic referred to Altman as “widely regarded as not ready for the mammoth task in front of him.” At Bleacher Report, another writer described Altman as a figurehead GM, “along for the ride” while the team’s ownership handled actual decision making. And LeBron, by that point just six months shy of his own free agency, was reportedly fed up with the whole mess.

And then came that flurry of deadline activity: two trades involving five teams, 10 players, and two future draft picks. For the Cavs, it was the basketball equivalent of a defibrillator: it might not save their season, but it provided a desperately needed jolt.

“We still don’t know if this is going to work,” Altman says, “but we feel a much better energy. The aura in the building is so much better.”

So, suddenly, were the headlines. Praise flowed in, from fans on social media, from reporters, and, most significantly, from his best player. “I think Koby did a heck of a job understanding what our team needed,” James told reporters a few days later. Griffin, meanwhile, took to Twitter to offer a proud told-you-so: “Koby Altman and the Cavs front office were never in over their heads, just handed a nearly untenable situation and have found a way to thrive!”

When we spoke in Cleveland, Altman had had the benefit of two relatively quiet weeks to assess both his new-look team and the surrounding noise. He had managed the seemingly impossible, making the Cavs better both in the short term—they’d strengthened the roster and jettisoned the potentially toxic elements in the locker room—and improving the team’s long-term outlook: A better team meant LeBron was more likely to stay beyond this summer, but if he left, the Cavs would be in a better position to survive his departure.

“Would I have been able to predict we could pull this off? No,” Altman says. “But I knew the stakes.”

He’d been aware, too, of the doubts, both within and outside the organization. Aware, but, he insists, unbothered. “What was concerning to me wasn’t ‘Is he ready,’ all that stuff,” he says. “What was concerning was that we weren’t playing well.” And so he ignored the noise and immersed himself in the work, now leading the decision-making team he’d recently been a part of.

He talks about the work of his analytics team, breaking down stats that don’t show up in conventional box scores. He talks about the scouts doing what he was doing five or six years ago, on the road relentlessly, noting the tendencies and weaknesses and strengths of dozens of opposing players, any of whom might someday be pieces in the Cavs’ puzzle. He talks about the phone calls and texts with agents and fellow GMs, informal fact-finding missions, all to gauge the possibilities. The process, he says, started long before deadline day.

In that, he might as well be talking about his own life. The love of a game, virtually sewn into his DNA. A gift for reading and understanding people, of relating, whether he encountered them on a Brooklyn playground, in a Manhattan skyscraper, or on the campus of a small liberal arts college. It’s an adaptability, and a knack for negotiation, and a competitiveness that doesn’t get in the way of his amiability but drives him just the same. That process, the one that readied him for all this, has been under way for 35 years.

Altman and his fiancée, Rachael Garson, are set to get married this summer (they asked David Griffin to officiate, and he’s getting ordained specifically to conduct the ceremony). Their daughter, Sophie Jane Altman, will be in attendance. Born two days after Christmas, Sophie was diagnosed in the womb with gastroschisis, a birth defect that causes the intestines to develop outside the body. It’s a manageable condition, and Altman says her prognosis was always good, but doctors couldn’t do anything about it until the child was delivered. In Sophie’s case, that meant spending her first 47 days in the neonatal ICU at the Cleveland Clinic, undergoing and recovering from a pair of surgeries before she could finally go home.

The trade deadline was February 8. She came home four days later.

“It was the craziest week of my life,” Altman says. “Those days around the deadline, I’d sort of skip out of the office, go see her for two hours, and not touch my phone. It wasn’t fun, but it was great perspective. And she got through it. She’s a fighter.”

If he seems unflustered by the pressure, by the weight of a city’s expectations, it might have something to do with all that. That sort of perspective holds up. Neither deadlines nor headlines can faze Altman now.

Ryan Jones spent seven years on the staff of the hoop bible Slam magazine, a tenure that included a stint as editor in chief. He currently writes from central Pennsylvania and tweets prolifically under the handle @thefarmerjones.

Leave a Reply