Over the past half decade, in the Andes Mountains of southern Peru, two bearded Americans—a couple of Middlebury Institute graduates named Aaron Ebner MPA ’11, and Adam Stieglitz MPA ’11—have made the same harrowing trip hundreds of times. Their starting point is the city of Calca, where they live, and their destination is Lares, a district on the other side of a mountain pass—14,448 feet above sea level—where a group of indigenous, Quechua communities with Incan roots are scattered. According to a 2005 report by Peru’s Ministry of Economy and Finance, as much as 97 percent of this population lives below the poverty line.

While economic indicators have improved slightly since then, thanks in part to improved roads, bridges, and national economic growth, Lares remains impoverished by any standard. Since 2009, Ebner and Stieglitz—under the auspices of their nonprofit organization, the Andean Alliance for Sustainable Development (AASD)—have worked and conducted research in the region, establishing long-term relationships with the campesinos who survive there by farming and raising animals on the steep mountainsides. Ebner (known locally as Ah-ron), Stieglitz (A-dam), and the AASD have, at this point, become household names. One day in June, during a trip to Lares, Stieglitz summed it up. “These days,” he said, “there are a lot of Aaroncitos running around.”

The route to Lares is a seemingly endless, terrifying series of single-lane switchbacks bordered by sheer drop-offs with no guardrails. Ebner and Stieglitz are accustomed to its peril, barely noticing the centimeters that stand between them and a long fall to the valley bottom; a commute is a commute. Maniacal truck drivers zoom by as if they were driving on Route 66 instead of rounding a 180-degree curve. Piles of boulders are occasionally strewn across both lanes by avalanches from the adjacent cliff. A herd of cows wander, made invisible by the fog until they are a foot away from the car window. And a male alpaca kneels on top of a female alpaca, focused not on the cars swerving around them but on furthering his kind.

It must be a rule, however, that the scarier the road, the more beautiful the scenery. The Lares road traverses the majestic Urubamba range, where fresh water streams down from the last of its vanishing alpine glaciers into sculpted green valleys below. Circular stone corrals dot the hillsides. A small lake, shrouded in mist, is silvery and still. Two young shepherds nap on an outcropping of rock, cocooned in blankets made from bright woolen ponchos. Power lines trace a parade of poles.

Since the AASD does not own a car or truck, Ebner and Stieglitz never drive themselves to Lares, instead relying on drivers to transport them, their staff, and groups of visiting students. On that day in June, a quiet man named Victoriano was driving. He lived in a community called Choquecancha, where the AASD has done a lot of work. His brother-in-law, Ruben Huaman Quispe, was one of the AASD’s cofounders and still works for the organization sometimes.

Victoriano named his five-year-old son Aaron (Ah-ron). As the car gained altitude, the fog thickened, and soon the edge of the road was no longer visible. An eerie, keening voice and accordian music filled the car’s interior; a huayno (Quechua folk song) called “No Soy Tu Criada” (“I Am Not Your Servant”) was playing on the stereo. A roadside sign said, Zona de Neblino, or Fog Zone, in case anyone hadn’t noticed. As we crossed the pass—a short, narrow canyon blasted through the mountain—a delivery truck barreled by like a ghostly monster, connecting isolated, sky-high communities to not only the cities below but the entire world. It was improvements in this road that brought most so-called development to these places, a fact that Ebner and Stieglitz had learned over the years. They had also learned that not all development was good.

“What if poverty was a question of sustainability?” Ebner asked from the back seat. For generations, these communities have been told they were poor and ignorant by outsiders from government agencies and international NGOs. “But if you look at how much they produce, and how little they waste, they’d all be considered rich,” he went on. “Instead, kids grow up here thinking, ‘We’re poor, we need to leave and go to the cities to make money.’” He looked out into the fog. “And who are we to say these kids shouldn’t leave?”

A young girl wearing a black and pink embroidered skirt and a bowler hat materialized, running out of the fog, followed by her herd of alpacas.

“Communities of course should develop however they want,” Stieglitz, who was sitting next to him, added. “But it doesn’t mean it should overshadow all of the skills, strengths, and brilliance that exist in their community. That sometimes they don’t realize they have.” Supporting the self-sustaining strengths of these remote communities, and changing the way their members, as well as outsiders, perceive poverty, is now a major part of the AASD’s focus, Stieglitz and Ebner explained.

The car began its descent into Lares Valley. After it rounded a sharp switchback, a young girl wearing a black and pink embroidered skirt and a bowler hat materialized, running out of the fog, followed by her herd of alpacas. She carried a magenta pink sack that glowed amid all the gray. Ebner rolled down his window. “Rufina!” In the middle of nowhere, in a dense fog, he knew someone. He knew her whole family, in fact. “Rufina!” he called again. She heard him this time, and a big smile of recognition flashed across her face. She ran to the car. They chatted briefly—something about photos of her that Ebner had on his iPhone and needed to email to her mother—then kissed goodbye. As quickly as she had appeared, she vanished.

The AASD is a small, unique NGO. Its mission is to support community-led development projects. Unlike other NGOs, at least those working in the Andes, one of its primary tactics has been the establishment of deep trust-based relationships with the communities in which it works. Since Ebner and Stieglitz started the organization while they were graduate students at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, they have also made academic research and experiential education key components of the alliance’s model. Their approach relies heavily on the help of students who take part in their courses and programs.

International NGOs have traditionally followed and, in many cases, still follow a top-down model of development. In the cartoon version of this model, an NGO shows up in an isolated, poor (by Western metrics) place and tells its residents what they are missing, or what will improve their quality of life, or what skills they should learn. NGOs dig a well, or teach some classes, or do whatever it is that they determine the place needs, despite having never lived there. Then, like a traveling circus, they leave.

Ebner and Stieglitz are critical of this approach but admit that their own mindset when they arrived in Peru was not so different. They gave lip service to the idea of community-led development, but actually came to the Andes like nouveau eco-missionaries, with a plan to build greenhouses next to schools. They believed that this simple idea could immediately create significant improvements in people’s lives. Instead, over the next eight years, they were humbled, frustrated, resented. Some of the greenhouses were ignored or unused, the victims of changing school directors or a lack of community ownership. Ebner and Stieglitz had many sleepless nights wondering what they were doing with their lives, and if their efforts had any value or impact. They spent years without salaries. But they also were not afraid to acknowledge their failures, their misunderstandings, and to use those experiences to help them refine and refocus the alliance’s mission.

Gradually, the AASD has made a small but steadily positive impact. School greenhouse projects led to family greenhouse projects, which turned out to be much more successful and sustainable. (Since 2012, they have helped 65 families build them.) Beginning in 2014, they began emphasizing the experiential-education arm of their organization and started collaborating with Middlebury professors to create courses for both graduate and undergraduate students. Students did a semester of in-class preparation for the work they would do on site in Calca—during J-term or summer recess—then another semester of follow-up reflection and analysis. (The AASD has also conducted an independent research practicum every summer since 2015.) These projects have centered around topics related to social change and communication, climate change, or, this year, school greenhouse gardens. The AASD has then presented its findings to organizations like Calca’s regional office of economic development, ensuring that community members’ wants, needs, and concerns are addressed on the larger institutional and governmental stage.

We’re not coming into these communities like Oprah: ‘You get a greenhouse! And you get a greenhouse! Everybody gets a greenhouse!’” Miller said.

In the last couple of years, Ebner and Stieglitz have been speaking to Middlebury administrators like Jeff Dayton-Johnson, the dean at the Institute; Susan Baldridge, Middlebury’s provost; and Jeff Cason, Middlebury’s dean of Schools Abroad, about how to formalize the academic relationship with the AASD. Dayton-Johnson and Cason even traveled to Calca last year to see the AASD’s work for themselves. They liked what they saw.

“To be truly effective and transformative, study abroad must be seen as more than a parenthesis in a student’s experience,” Cason told me. “The kinds of things that AASD brings to the table—original research and hand’s-on development work—are precisely what can make for an extended and integrated experience.” A partnership with Middlebury, Baldridge and Cason said, could facilitate new opportunities for immersive, place-based learning. So far, however, the mechanisms for creating and situating such a partnership have yet to be defined.

At present, unable to offer financial aid or academic credit in most cases, the AASD has struggled to get motivated, qualified students to come to Calca. This summer, Ebner and Stieglitz had hoped to recruit 12 students to take part in research specifically about Peru’s national school lunch program, known as Qali Warma, in partnership with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. The FAO wanted to know whether a nationally administered school greenhouse program would improve school lunches, which are criticized for their lack of fresh produce. Ebner and Stieglitz had hoped students would interview families in the Lares communities about their kids’ nutrition, the school lunches they received, and the challenges and benefits of the greenhouse gardens they had built. From years of experience and analysis, Ebner said, the AASD has come to believe that investing in a national school greenhouse program would be the most effective way of improving children’s diets. “But we want the data to back it up,” he said. Ultimately, due to a lack of financial aid, only three visiting students were able to participate. They still conducted the research, but it was limited in kind and breadth. The AASD hopes to be able to do qualitative and anthropological research on the same and related topics with future contingents of more experienced and language-proficient students.

Provost Susan Baldridge, a big supporter of the AASD, suggested to me recently that such a contingent might soon have an easier time getting to Calca. In October, she said, Middlebury’s Board of Trustees will vote on whether to adopt a new strategic plan. One of the plan’s aims will be the development of intercultural competency in students. “We didn’t design this framework with the opportunities that the AASD offers in mind,” she told me. “But they are the perfect illustration of exactly the kinds of things we want to do to move forward strategically.”

Ebner and Stieglitz, she added, “were the poster children for place-based experiential learning,” which aligns with Middlebury’s mission and values. “They are very serious about the idea that the impact they can have must build on the wisdom of the local community,” she said. Moreover, Baldridge finds them to be compelling, sincere, authentic leaders. “There is a really appealing humility about them,” she said, “even while their ideas are bold and audacious.”

To date, about a dozen Middlebury undergraduates have worked with the AASD in Calca, and their reports about the experiences are promising for the alliance’s future. Evelin Toth ’17, the valedictorian of her class, recently told me that the summer she spent working with the AASD, in 2015, “was a really powerful experience.” (Her time in Peru as sponsored by the Ambassador Corps program.) “I had the opportunity to interview indigenous communities about their traditional agricultural practices,” she wrote in an email. “I became more aware of the reality of climate change and the ways vulnerable communities are coping with the impacts.” The experience also directly informed her postgraduation pursuits. She is currently in Bhutan on a Watson Fellowship, researching how climate change impacts that nation’s mountain communities.

Charlie Mitchell, a current Middlebury senior who also went to Peru with the Ambassador Corps program, spent the summer of 2016 designing a food studies J-term course with the AASD and the guidance of his advisor, Professor Molly Anderson. “I learned a lot about the complexities of ‘development’ as we understand it today,” he told me, “and had very valuable discussions about rethinking our conception of poverty and sustainability.”

While Ebner and Stieglitz have started courting other academic institutions, they remain hopeful that something more will happen with Middlebury. “The Middlebury students that we have worked with have been exceptional,” Ebner said. “Smarter than either of us.” Several Middlebury Institute alumni have traveled down to Calca and stayed with the AASD after their internships or independent studies ended, including, most notably, two current senior staff members: Gaelen Hayes, the experiential learning program manager, and Christopher Miller, the director of organizational development. Miller told me that he especially values how the AASD establishes long-term relationships with the people who live in the region. Their approach, he added, couldn’t be more different from big governmental or NGO development projects. “We’re not coming into these communities like Oprah: ‘You get a greenhouse! And you get a greenhouse! Everybody gets a greenhouse!’” Miller said. “We know that’s never going to work. Instead, we go to these community assemblies and present these ideas to everyone. Those who are really open to it, really see the benefit of it—that’s where you’ll see success.”

Jagged ridgelines loom over Calca, a sleepy city of about 20,000 inhabitants, located at the eastern end of the Sacred Valley of the Incas. It remains one of the few cities left in the valley that has not been overrun by Machu Picchu tourists wearing breathable fabrics. There is only one ATM (which the owners of my bed-and-breakfast didn’t know existed); the Wi-Fi, when it works, is not much faster than dial-up; and cell-phone service is spotty at best. Power lines hang low, meeting on corners in angry tangles. Miniature, three-wheeled moto-taxis toot for passengers, spewing exhaust. Packs of roaming feral dogs rule the narrow, cobblestoned streets.

Ebner, who grew up in a small town in Michigan, first heard of Calca after a tragedy. His cousin, Becky Prichard, whom he had never met, lived in Calca and started a restaurant in the neighboring town of Pisaq. In 2003, just 30 years old, she died in a car accident. In her honor, her mother started an organization called the Becky Fund, which worked to help Peruvian children in the Sacred Valley, as her daughter had. In 2006, with the Becky Fund’s support, Ebner started traveling to Calca to help community schools with various carpentry projects. He got to know the people who lived in the area and started to think about bigger solutions to some of the challenges they faced.

The climate is harsh in these high-alpine communities and most farmers can grow only certain varieties of corn, grain, and potatoes. And in recent years, they have struggled to cultivate even these traditional staples. The seasons, which previously had been clearly divided between wet and dry, have become increasingly unpredictable. The wet season is far more wet than it used to be, and during the dry season, the only source of water is glacial runoff. For all of these difficulties, many people’s diets lack essential vitamins and nutrients. In the most severe cases, exacerbated by extreme poverty, children suffer from malnutrition, which impairs their immune systems and intellectual capacity. Ebner began learning about methods for constructing mud-brick and plastic-sheet greenhouses that could grow a wide variety of vegetables and fruits at the highest altitudes and thus dramatically improve children’s diets. He wanted to know how he could he help communities build and maintain them?

In the fall of 2009, partly in order to answer that question, Ebner enrolled in a master’s program in public administration at the Middlebury Institute. A scruffy guy from Florida named Adam Stieglitz was one of his new classmates. “I distinctly remember thinking, I’m probably not going to be friends with this guy,” Ebner told me. “He was sitting right in front of me, flirting with this girl, and she wasn’t having any of it. I just thought, ‘What a tool.’” (The feeling was mutual. “I thought he was an asshole,” Stieglitz said, recalling his first impression of Ebner.)

Friction is necessary to make a spark. They quickly became not only good friends, but ambitious collaborators. Within a year, they had built their first two school greenhouses in a community called Pampacorral, near Calca, and within another, they had cofounded and incorporated a nonprofit organization, the Andean Alliance for Sustainable Development. With $5,000 of student loans each, they moved to Calca in the summer of 2011. The AASD headquarters was the living room of whatever apartment they could afford to rent.

A turning point came a year later, when Ebner and Stieglitz were forced to make a decision that would affect the AASD’s entire trajectory. “It was the moment when we realized we could not be the development organization we thought we would be,” Ebner told me. They were working with a big agricultural development project funded by the Canadian government. The project managers wanted the AASD to build “a bunch of greenhouses in 15 different communities,” Ebner said, “and would pay us a lot of money to do it. But we had to get it all done in three months. Top-down.” Ebner struggled with the decision. “It would have been more money than we ever made ever,” he said. But ultimately, they felt that if they agreed, they would be unable to maintain their principles. “We had to stick to our guns,” he said. “We don’t want to be an organization that is accountable to funders. We want to be an organization that is accountable to our communities.” They turned down the offer.

Funding became an increasingly urgent issue. It was clear that if the AASD was going to make its own money—and not rely on big grants or major foundation partners—then it needed a new business model. Ebner, Stieglitz, and other staffers started discussing a hybrid of social enterprise and community-led development. They would offer students varying types of academic programs in Calca centered on research or on cultural exchange that would add value to the lives and work of community members. They formalized their experiential-education programs under the umbrella of what they dubbed their Center for Andean Studies; such programs now make up 80 percent of the AASD’s gross revenue.

In late June, the place was a hive of activity, reminiscent of a San Francisco start-up, perhaps, though more haphazard, bohemian.

So far, the model seems to be working. Two years ago, the AASD moved into its own building, and Ebner and Stieglitz began paying themselves a livable wage. (They were only paying themselves each $6,000 annually the previous few years.) They also hired Julio Cesar Nina, an organic farmer from a community next to Calca, to help them with agriculture projects and translate Quechua. Nina, an amateur historian, had long been deeply suspicious of the entire Western notion of development, and he was critical of the governmental agents and international NGOs who had shown up to “develop” indigenous parts of Peru for generations. But he eventually started to see that the AASD was different. “It’s the way they propose projects,” he told me. “They always originate from the campesinos, and not from institutions or governmental organizations. That is to say, the projects we suggest come from the bottom up.”

AASD’s new headquarters is located on top of a hill on one of Calca’s main streets. A massive pisonay tree grows out front. The tree is visible for miles, as if, on a map, someone had stuck a giant pin into the AASD coordinates. Since Ebner and Stieglitz often encourage community members to visit, this is especially useful; everyone knows how to find them. Beyond a sliding red steel gate, there is a small weedy courtyard where Ebner parks the AASD’s red motorbike. A small brown door leads into the actual building. Most AASD staff members have to duck their heads when they enter.

In late June, the place was a hive of activity, reminiscent of a San Francisco start-up, perhaps, though more haphazard, bohemian. Young men and women typed on brushed steel Macbooks, sitting in tattered, oversized armchairs or on giant inflatable balls. Desks were scattered among several rooms, along with bicycles and AASD trucker hats. In the kitchen, two current Institute graduate students (who lived in rooms on the premises) made scrambled eggs, while a boy in a white undershirt (Ebner’s younger brother Eric) brushed his teeth at the sink. Leroy, the alliance’s huge furry mutt, wagged his tail, taking up the rest of the space.

Ebner and Stieglitz were sitting at a big table on the back patio, finishing breakfast, dressed like off-duty ski patrolmen—long underwear, flannel button-downs, puffy down jackets. Although this particular morning marked the start of one of the busiest weeks of the AASD’s year, they seemed relaxed. Ebner was drinking a glass of chocolate milk and was talking about surfing. Stieglitz, who bears a resemblance to his famous great-great grandfather, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, insisted he was stressed. “This is me at peak anxiety,” he said, in his distinctive gravelly drawl, sounding like a cross between Tom Waits and Jeff Spicoli.

In the breakdown of alliance work, Ebner and Stieglitz have increasingly taken on particular focuses. The AASD’s finances, documentation, and outreach are Ebner’s domain. He and his brother Eric had spent the spring filming a documentary about a potato farmer in the area who cultivates more than 300 varieties. The story aims to showcase the strengths of the Lares. Ebner wants to upend the tropes about Third World poverty that photographs and documentaries—often those distributed by NGOs—have perpetrated in the past. Stieglitz, meanwhile, has been “diving really deep into the convergence of academia and community development,” he said. He was much more involved in the experiential education side of things. At the moment, with several student programs in progress, his docket was not only full but presenting potential problems.

Of immediate concern was the summer research program on school greenhouses, which seemed to be on the verge of unraveling. A nationwide teachers’ strike was under way, which could make it harder for them to conduct their research, since parents in the communities would be busy with their kids, who weren’t at school. Furthermore, the program’s four undergraduate participants—who had recently arrived in Calca—were meant to visit their first community the next day, then survey eight or nine more communities by the end of the following week. It would be a grueling pace, the result of having such a small research group.

Except that earlier that morning the group had gotten even smaller. At 9 a.m., two students, instead of four, had arrived at headquarters. One of the missing was still in bed, reportedly. She hadn’t slept a wink the night before, probably due to a mix of culture shock, street noise, and altitude sickness. The other missing student had, it seemed, decided to return home to the U.S.

With one fewer person, what had been daunting now seemed nearly impossible. But they would have to make do. That afternoon, Stieglitz said, they needed to review the survey’s final draft, practice how they would ask community members questions, and discuss how people might respond. Ultimately, their aim was to gather quantitative data regarding the community’s perspectives on school greenhouses, school lunches, and the ways that fresh produce might be incorporated into the national school lunch program. They would start analyzing their results in two weeks, once the fieldwork was complete.

Stieglitz wanted to make a few things clear. The work would be hard and the physical conditions tough. Other organizations might advertise their programs as ones that would instantly lift people out of poverty, but that’s not going to happen, he insisted. He told the students that they were there to learn from the people as much as they were there to help them. That’s how progress is made. “Finally,” he said, “we’re starting to open some doors that not many other organizations have walked through.”

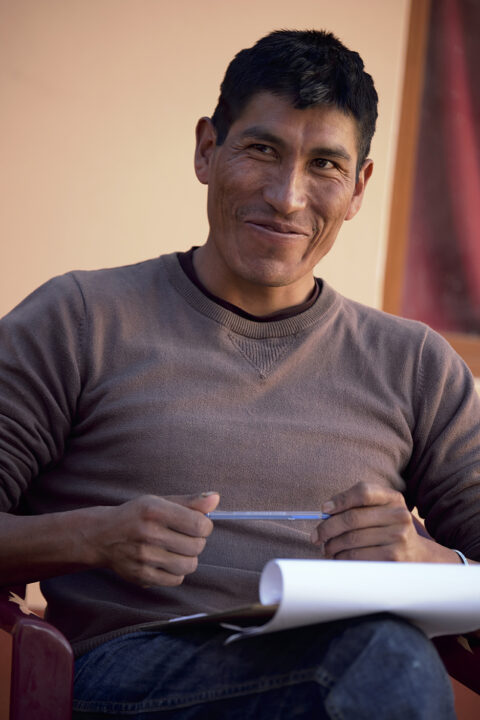

Julio Cesar Nina, the farmer, arrived at the AASD’s headquarters that afternoon for survey practice. Thirty-five years old, he was tall and broad-shouldered, with a square jaw and a huge, slightly goofy smile. He walked with good posture and didn’t seem like someone who could ever lose a wrestling match or a fistfight, except that he also seemed like a person who would never find himself in either situation.

Nina had a big job over the coming weeks, since he was the only Andean Alliance staff member who could actually communicate with most residents in the more remote communities. They spoke Quechua. The awkward plan was for the students, who spoke rudimentary Spanish, to ask the community member their survey questions, followed by Nina’s Quechua translations for the community members, and vice versa. The students would try to understand and record responses by hand in English on their surveys. It was a cumbersome process, but Nina didn’t mind. Talking to farmers and farming families is one of his favorite things to do.

After so many decades of colonization, oppression, racism, and abuse, Nina wants passionately for these indigenous communities to regain their confidence and autonomy. He is a vehement critic of most rural development efforts, but as the Andean Alliance stuck around Calca, year after year, Nina saw that its staff shared his ideas about rural development. So in 2015, when Ebner offered him a full-time job working on sustainable agriculture projects in the distant Andean communities that he loved so much, he agreed. “For generations now, in the name of development, the Peruvian government sent agricultural technicians to rural communities. The implicit message always was, ‘We have the knowledge and not you,’” Nina told me. “This pattern left a legacy of shame, ignorance, and a cycle of poverty—a mentality like, ‘If I say I’m poor, and I act poor, I will receive resources.” The widespread practice of seed saving, for instance, was lost when the government began giving seeds to the campesinos. “This caused major damage,” Nina said firmly.

Ebner told me that Nina and his sister Yésica, who is also a farmer, are master seed savers. Seed saving allows for healthy and diversified crop rotations, as well as experimentation—something that is especially important in the face of climate change. Seed saving can ensure that community members will be able to maintain continued production in school and family greenhouses instead of waiting for NGOs or the government to donate another batch of seeds.

Nina and Yésica grew up on the farm where they still live. They have always had a passion and knack for agriculture. In her late teens, Yésica lucked into a youth exchange trip to the United States. She ended up on an organic farm in California (where she also met Ebner). When she returned home, she was an organic evangelist. Until that point, her family had been considering selling their farm and moving to the city. Instead, she convinced them to do something that seemed even more drastic—help make their fields and crops chemical-free. The experiment was a radical success.

The siblings began teaching popular organic farming classes at their home and inviting entire communities to come to workshops together during fainas, or specially designated communal work days. They are currently building a second, larger classroom on their property to expand this work as well as the types of agricultural projects they can run as experiments.

“I think knowledge is the most important thing,” Nina said. The legacy of colonization and development had stripped or corrupted much of the indigenous community’s knowledge. And, perhaps more importantly, it had left deep psychological wounds: shame, self-hate, apathy. “The campesinos themselves have to rebuild their self-confidence, leave behind this timidity and fear, and learn to adapt to the changing conditions,” Nina went on. No one else can do it for them. “They must be the authors of their own development.”

Several days later, Nina was sitting on a street curb in a village called Cachin, talking to the president of the community parents’ association—the Andean version of the PTA—about school greenhouses. “We want to make the greenhouse bigger,” the president told Nina, “so that it can provide for the entire community. Not just the young students.”

Nina countered that perhaps it made more sense to help build 10 to 20 family greenhouses instead of expanding the primary school greenhouse. Since 2010, the AASD has supported construction of 13 school greenhouses in 5 communities and 65 family greenhouses in 6. Ebner told me that the family greenhouses have been more sustainable than the schools’, which have fallen victim to indifferent administrators or a high rate of turnover among enthusiastic faculty.

Moreover, the family greenhouses have increasingly gained in popularity throughout Lares and Calca. “I have a list on my wall of 20 communities where representatives have stopped by our offices asking for family greenhouses because they heard about them from a neighbor or a school project,” said Chris Miller, the organizational development director. “When we do those projects, we’re there only as a point of support. We tell them, ‘We’ll do workshops with you on composting, for instance, and check in from time to time.’ But we’ll also say, for instance, that ‘the plastic will degrade in five-ish years, and it’ll be your responsibility to save up the 300 soles (about $100) it will take to replace it.’ We’re seeing that when we give people that autonomy, their ownership of the greenhouse increases significantly.”

In one of the highest-altitude communities in Lares, way above the tree line, one family built a greenhouse 14,500 feet above sea level. They’ve been able to successfully grow grapes, tomatoes, strawberries, and even mangoes. In that same community, called Pampacorral, Miller told me, a kid named Alfredo was part of the first wave of students that got to experience school greenhouses. His mom then was part of the first family greenhouse project in a neighboring community. Finally, in 2014, Alfredo built his own greenhouse in Pampacorral during a second AASD round of funding for construction. He made the mud bricks and built the structure; AASD simply provided plastic for the roof.

No one knows with certainty what sustainable development should be. Perhaps every corner of the world requires a unique solution. Part of the AASD’s success hails from the decision Ebner and Stieglitz made to keep the AASD small and to focus on relationships in one place, rather than scaling up. The organization, they say, wouldn’t work if it got much bigger and spread to other regions. “Social change is slow and requires leadership and trust and long-term commitments,” Ebner said. He doesn’t see how those principles can be applied uniformly on a grand scale.

What is scalable, they say, is their hybrid model bridging experiential education with community-led development. Stieglitz believes it will revolutionize the future of education and cross-cultural exchange, and will spread around the world. He sees universities working with other small NGOs to support their grassroots development efforts by sending students to help them. Students, in turn, have new hands-on and place-based learning opportunities. The model has endless possibilities, some of which have been piloted at Middlebury already: undergraduate students working with a regional economic development office to evaluate their programs, network with other experts in a particular field, and help the office adapt the program to make it better; and wraparound courses that precede and follow a student’s research done in Calca. “It’s not just about a three-week experience during J-term,” Stieglitz said. “It’s everything leading up to that and what comes after.” He imagines an evaluation class in which students design a way to evaluate one of the AASD’s programs, then go to Calca and carry it out; or a live case study, in which people in a community in Peru are involved in the class taking place at Middlebury. “It’s about building that cohesion,” he said. “Experiential education is adding value locally, in Peru.” But in their model, it’s “not just about students coming in and helping communities. There is also this bilateral flow, push and pull—what students are taking away from these brilliant sustainable communities as it relates to their studies.” While he still is deeply involved in the AASD and plans to remain so, Stieglitz just started a PhD program in Kentucky. He wants to put all the work the AASD has done under a microscope and scrutinize it, as well as further develop his experiential education ideas.

Can development work ever be rid of the neocolonial taint? Isn’t there always a power imbalance, a presumption of superiority, or a lack of mutual understanding? “I think about it every day,” Miller said recently. “I once asked Julio, ‘Man, why don’t I just leave? My salary could just go to build so many more greenhouses.’”

“Look, we play an important role,” Nina had responded, as if it were the simplest question in the world. “Think about when you make a New Year’s resolution to go to the gym. Alone, you’re probably gonna fail. The way that you’re gonna succeed is if you rope in your buddy, you guys start going together.” The same goes for building greenhouses, saving seeds, joining a textiles collective. “The communities want to be doing these things,” Nina told me, “but sometimes they need a little spark, a helping hand to get going. And that’s what we do.”

Contributors

Leave a Reply