In her line of work, costume designer Mira Veikley is used to making do. The assistant professor of theatre learned—during what she calls her “scrappier” days as a freelancer in New York City—how to “work with what you have.”

Veikley had to call on that scrappier part of herself in March when the College announced that, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be sending students home to finish the academic year remotely. She would have to figure out how to teach her two largely hands-on classes without the resources of the Theatre Department or the Costume Shop.

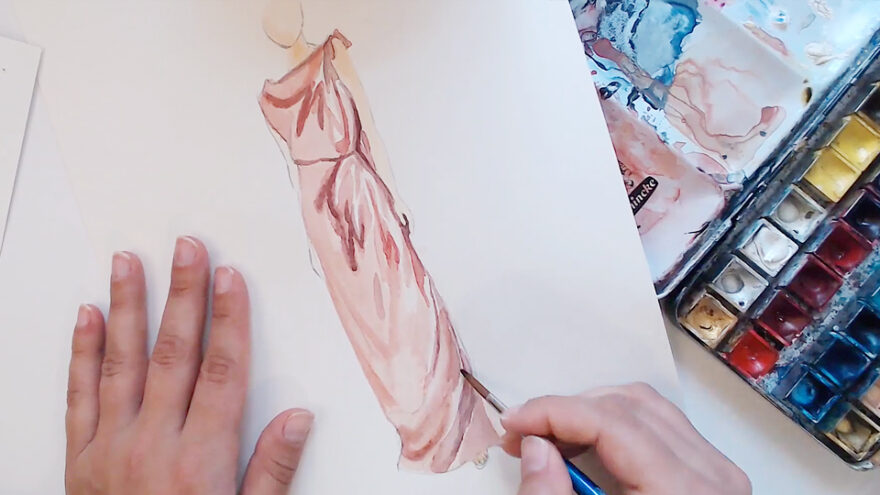

In one sense, the timing was lucky: for several years, Veikley had been working with Middlebury’s Digital Collections project team on a grant-funded project to digitize the College’s antique clothing collection. By coincidence, the site launched just before the College closed, giving students in her Advanced Costume Design II class online access to images they could use for their painting and drawing studies.

Her Production Studio class proved more difficult, as the students had been in the process of building the costumes for the spring production of Julius Caesar. Not only would they miss learning to cut, dye, and sew in the Costume Shop, but most didn’t even have sewing machines at home. What’s more, the fate of the play itself was up in the air.

For both classes, Veikley had to find a way to connect with students all over the world. She knew that, with time differences, live classes on Zoom wouldn’t work. But, through the Office of Digital Learning and Inquiry (DLINQ), she eventually landed on Panopto, a presentation platform that allowed her to record a lesson showing two screens simultaneously: one of her hands demonstrating a painting or sewing technique, and another of her face speaking directly to the camera.

The format lent itself to student presentations as well. Being able to see the students’ faces was essential in the costume design class, Veikley explains. “Costume designers have to ‘sell’ their concepts to the directors. You can see when someone’s excited about a design. I was happy we could preserve that energy even though we weren’t meeting live.”

Panopto also helped with Production Studio, whose curriculum Veikley revamped with what she calls an “à la carte menu” for students. She made sewing demos for those who had machines and wanted to keep sewing. For others, she provided links to different content, such as videos about backstage work.

Veikley laments that some students were “a little defeated” by the new circumstances, but the way others immersed themselves in their work was “awesome and thrilling.” And she sees other positives. “For one thing,” she says, laughing, “we all learned a lot about tech that we’d been putting off for a long time.” The Theatre Department and its students overcame their biggest challenge, the inability to produce Julius Caesar on stage, by reworking it as a Zoom production.

“There was also a realization of the things I took for granted before, like being together, having moments of physical access to material, antique garments. I have a newfound appreciation for what will eventually come back.”

Veikley has found a new sense of community with others in her field, as faculty from many institutions have flocked to online educators’ forums to share ideas and resources for teaching remotely. And on a personal level, she has become more comfortable making, and learning from, mistakes. “In a normal semester, a mistake feels more like a defeat. This semester, any success felt super successful, and defeat felt like, ‘Well, that’s where we’re at, now I know what to do.’”

So what does the fall look like?

“We don’t have the answer yet,” Veikley says. “But we’re thinking about our students and thinking about how we can give them a really valuable experience, even though it’s not what they would have had.”

She doesn’t sound too worried. “We’re theater people,” she says. “We’re really innovative. We like to solve problems.”

Leave a Reply